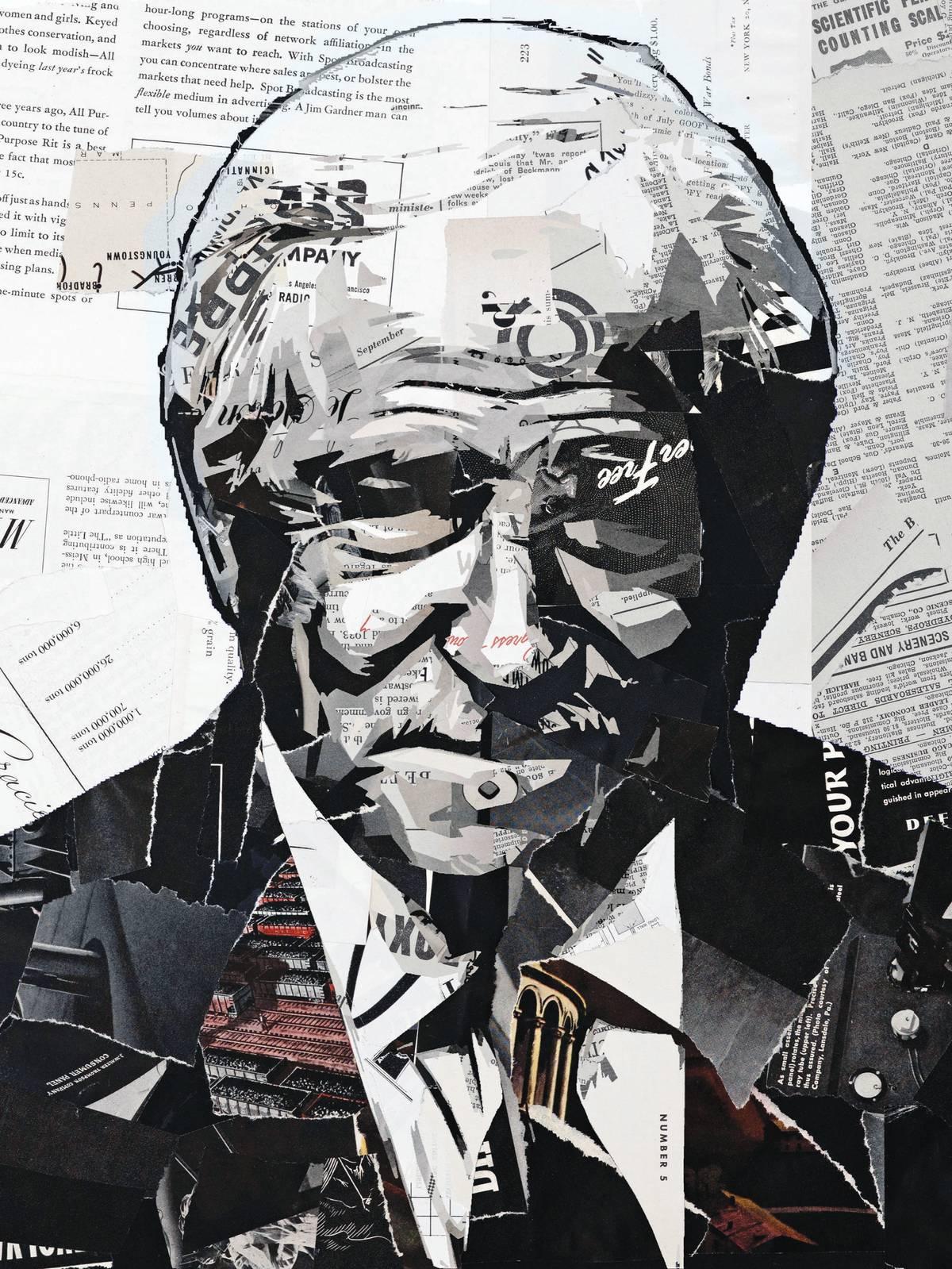

Photo by Jim Graham

On the eve of his retirement, local media icon Jim Gardner looks back on his career and his 45 years at 6abc.

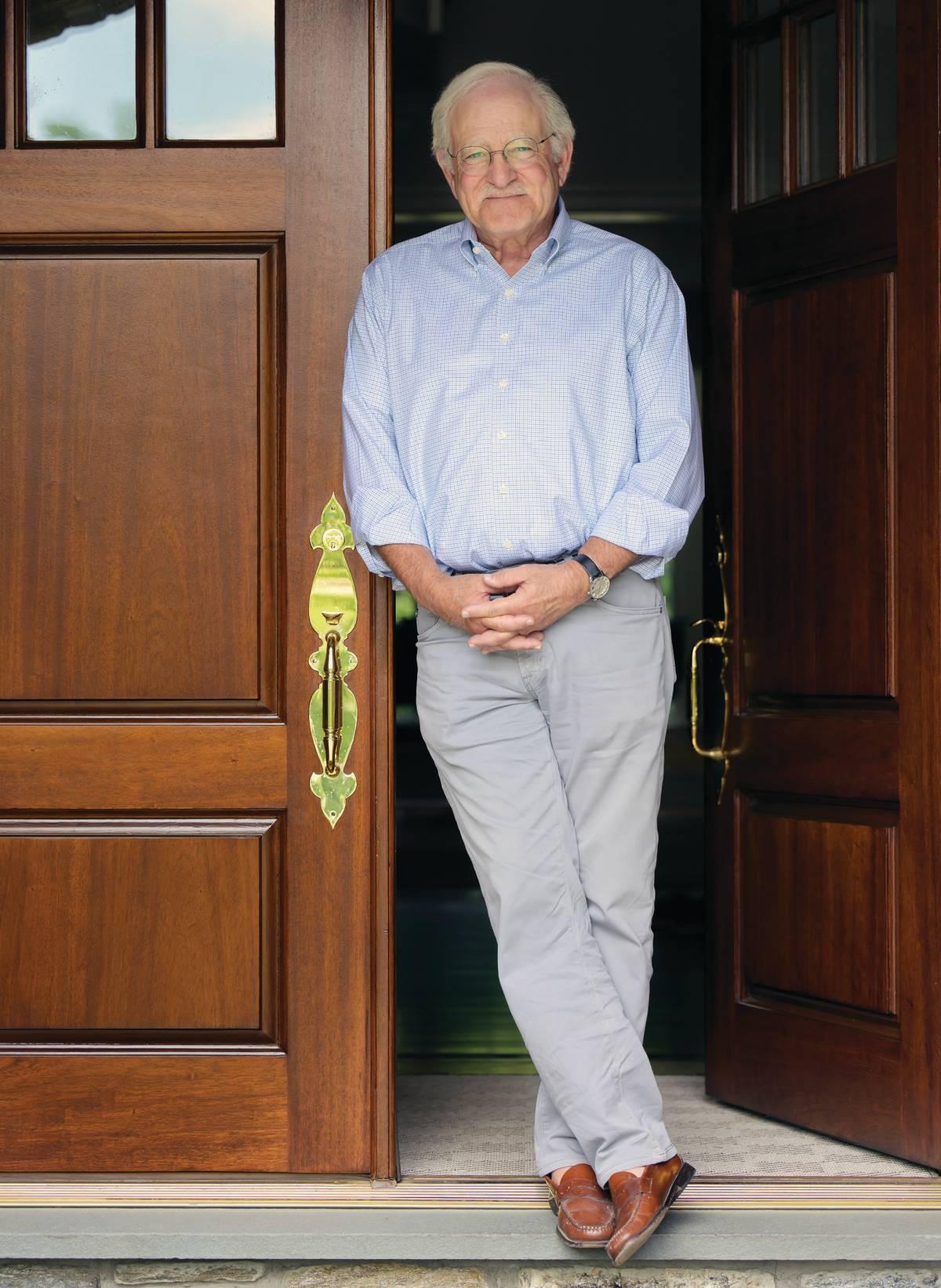

Jim Gardner, it seems, can’t avoid the big story—even on vacation. Amy Goldman, his wife of 25 years, slides open the patio doors and briefly steals the spotlight. “It’s a big news day,” she says. “Roe v. Wade was overturned.”

Then she heads to the gym.

You are viewing: Who Is Jim Gardner’s Wife

“Come January, it has to end, and I have to deal with that,” says Gardner from the back porch of the Villanova home they share. “It’ll be a process, but it’s clear that I’ll need to feed this aging and decaying brain with something.”

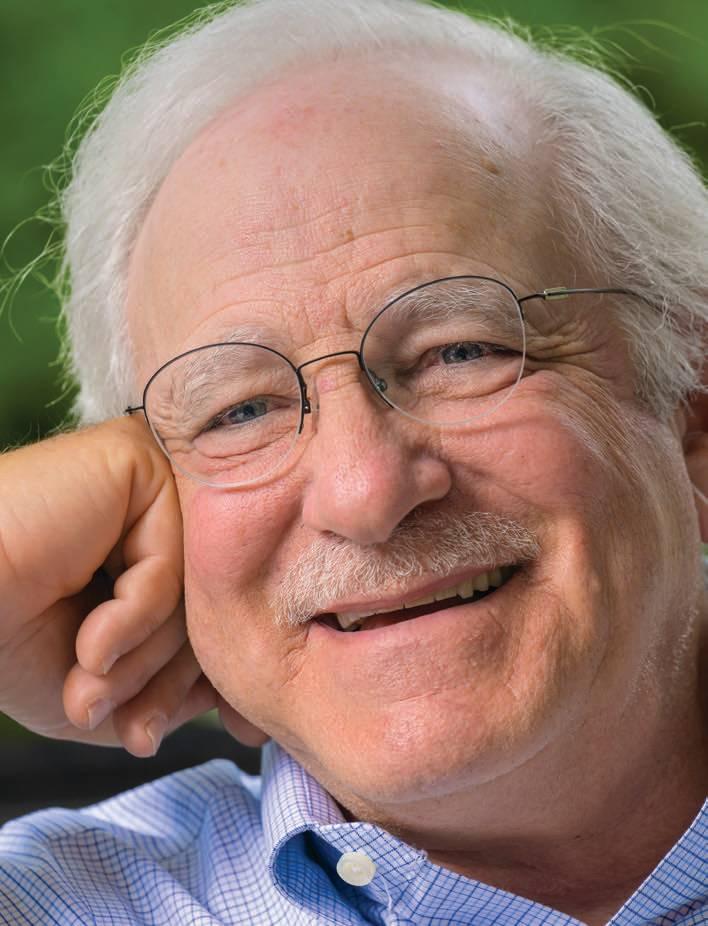

At month’s end, Gardner will finish his 45-year run at 6abc’s Action News, the longest tenure of any on-air personality in Philadelphia. This past January 11, he anchored his last 11 p.m. broadcast. On December 31, he’ll officially retire from the station. “On January 1, we’ll be watching bowl games,” says Gardner, now 74. “Come January 2, what will I do? It’ll be cold, so I won’t be practicing my short game.”

Born James Goldman and raised in a reformed Jewish family, the native New Yorker still insists that he stumbled into his anchor seat. Today, he’s most proud of his longevity and his consistency. “Say someone was 15 when they started watching me, and now they’re 60—and I’m still here,” he says. “You could say I was a part of their life’s journey.”

Indeed, Gardner has been a fixture in countless Delaware Valley living rooms for decades. “Now I’m an antique—and an antique they’ve found they can’t get anything for,” he quips.

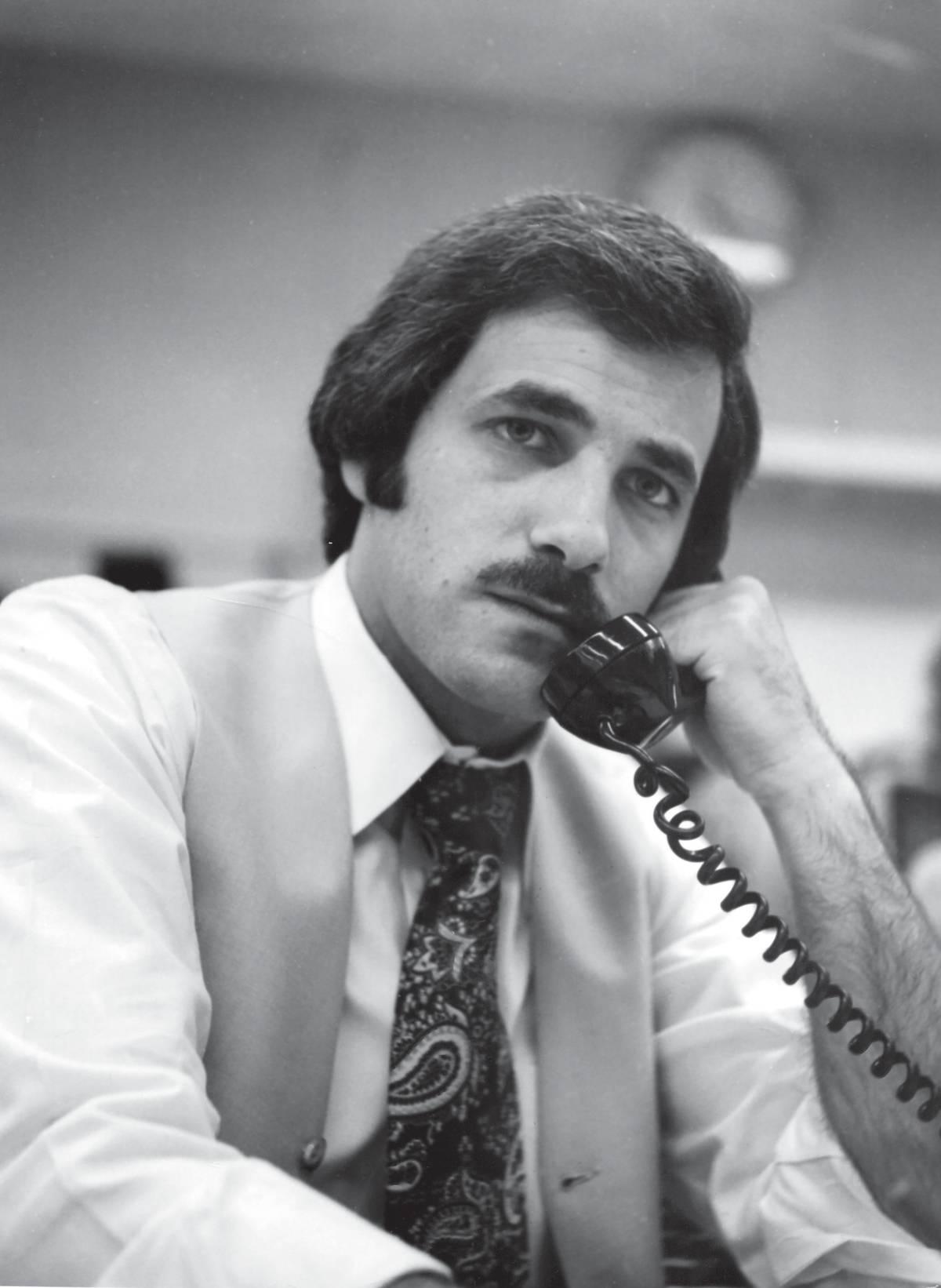

Gardner’s star rose meteorically in Philadelphia. He joined WPVI-TV Channel 6 on June 1, 1976, a month before the nation’s bicentennial, as a reporter and noontime anchor. By November, he was anchoring the 5:30 p.m. news. On May 11, 1977, six days before his 29th birthday, he became anchor of Action News at 6 and 11, replacing Larry Kane. That same year, Action News won a television sweeps period by a wide margin, and its hold on the local market has been (briefly) challenged only twice since. One would think Gardner has something to do with that.

Initially, Gardner couldn’t land a TV job. He’d begun in radio in New York, and while he inquired everywhere for two years, hiring managers told him to call back after he’d had his first job in television. By 1974, the Columbia University alum had decided to return to campus for postgraduate work at Brown. Then WKBW-TV in Buffalo asked him to be a news reporter. Within six months, he was weekend anchor and a weekday substitute. His first big story came when the station’s veteran anchorman was on vacation: Richard Nixon resigned. In January 1976, Gardner launched WKBW’s lunchtime news program. It became the most highly rated noon newscast in the market.

WPVI-TV general manager Larry Pollock had also worked at WKBW. He brought Gardner to Philadelphia. “He was like my rabbi, really,” says Gardner of Pollock, who died in 2019. “He had the confidence in me when others didn’t. It was absurd, but I think he thought I’d be one to stay here a very long time.”

And so he has—though his early days in Philly were fraught with friction. Veteran weatherman Jim O’Brien figured he’d been passed over when Gardner was anointed. Their terrific on-air relationship was a mirage during the first six months. They didn’t talk off air. “I needed his support, his tutelage, and he was worried we’d crash and burn,” Gardner recalls. “I was a kid, so what did I know? It’s true. I was so unprepared, I didn’t know how unprepared I was.”

When Pope John Paul II came to Philadelphia in 1979, the station aired 15 hours of unscripted coverage with Gardner as anchor. Anything but an expert in Catholic ritual, Gardner bought every book on the subject at the University of Pennsylvania bookstore. “When it was over, I felt like I could do this,” he says.

Gardner would also be on Jordan’s Mount Nebo when Pope John Paul II made his pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 2000. “I’ve had enough of these experiences to say it’s been worth it,” he says.

Jim Goldman was 8 or 9 when his father, Joseph, first told him that “having fun for the sake of fun was a waste of time.” Everything and every day, his father said, had to beget another accomplishment. He couldn’t seek refuge with his mother, Florence. She’d been ill from his preteen years, dying at age 55. His father was remarried to the daughter of Mordecai Kaplan, founder of the Reconstructionist branch of Judaism. Gardner has two older sisters; one has passed. “It wasn’t a happy-go-lucky childhood,” he says. “Among those who know me well, they’d say I still have trouble having fun.”

Read more : Who Invented Sickness

Gardner inherited an incredible work ethic from his father. “In one respect, I still struggle with it,” he says. “I grew up listening to him talk on the phone, and he was really tough. I hate to say it, but he was often unkind. Then I grew up, and I began to realize that I could be unkind. Not anymore, but for more than a few years, I could be unkind, too. I didn’t show respect to others.”

The 1968 Columbia University student riots were a proving ground for Gardner. Until then, he was “playing” at the school’s radio station, covering basketball and football. The station was owned by the school’s trustees, and they weren’t at all comfortable with the extensive riot coverage. After the station’s transmission lines were cut to keep it from broadcasting, the New York Times became their outlet. “It was a lesson in ingenuity and getting the job done, but it was difficult for 19-year-olds,” Gardner recalls. “You try to be even-handed, but we were covering the news and also comforting friends whose heads were beaten in—or friends who were being loaded into police vans. It was an impression-defining, epiphanous time for me.”

Gardner began as a pre-med student. Also a Columbia grad, his father was a heralded New York City ear, nose and throat physician. From age 5, Jim was told that he’d follow in his dad’s footsteps. “But I didn’t know what that meant,” he says.

Gardner’s grandfather was a tailor, so there was only enough money to send one of his three children to college. Joseph was supposed to become a tailor. Instead, he took the subway into Manhattan and talked himself into Columbia, tuition-free.

Gardner isn’t particularly comfortable discussing family. “This is excruciatingly painful,” he says at one point during our interview. “It’s not who I am or what I do. If it was up to me, I’d do my last newscast and go away. But if I’ve been present for people over their lifetimes, I guess I do also want to say goodbye.”

Largely private, Gardner has gradually opened up to some public exposure. “Over time, I’ve learned to overcome the feelings of awkwardness, but I’m not a gregarious person,” he confesses. “For many years, some took my shyness or social reticence as being aloof or uncaring. Thankfully, I’m now more relaxed and comfortable.”

Though he demanded perfection from himself, Gardner finally realized he couldn’t impose that on others. “I just had to change,” he says. “I’m a different person today—and I’m proud of that. But there are still some at Channel 6 who will tell you, ‘Oh, he used to be brutal.’ I’ve even asked for forgiveness from a few. I’ve endured some emotional moments in an effort to cleanse.”

Jamie Pschorr, Gardner’s producer for the 6 p.m. newscast since March 2011, is a tough cookie herself, having completed 11 Boston marathons. She concurs that Gardner has softened. “I hear stories about Jim back in the day, and I know I came along at the right time in his career,” she says. “He’s learned that you can still be demanding and have standards, but you don’t have to do it in a callous way. You can be an example of your standards without being demeaning.”

Longtime Channel 6 weatherman Dave Roberts met Gardner in 1974 when they were first paired in Buffalo, following him to Philly in May 1978 and eventually taking over for O’Brien after his death in a skydiving accident in 1983. He and Gardner became great friends. “The first day, there was a handwritten note Scotch-taped to the wall in my assigned office that said, ‘Welcome, my friend. I’ll see you later this afternoon,’” remembers Roberts, who retired 12 years ago and will turn 87 in February. “We always liked one another. What people saw on air was authentic, and we found that the public liked normalcy and honesty.”

Roberts has embraced Gardner’s transformation. “It brings pure joy to my heart to see where he’s at now,” says Roberts, who lives in Haverford. “As anchor, I’ve seen him achieve and explode. He’d lose his cool if a story wasn’t edited properly. He was intense, very intense. But he was the best newsperson I’ve ever worked with—and when he realized he was extremely hard on people and difficult to work with, he felt remorse. He’s gone back and apologized. It’s been a penance he feels he has to do to complete his professional journey.”

Pschorr says her earliest days with Gardner were a trial-and-error period. “I felt like every day I was studying for a test,” she says. “He had such high standards.”

Former news director and general manager Dave Davis notes that Gardner has never based his career on awards. “He was all about the audience, and the people, and doing the best job possible,” says Davis, who retired four years ago after 41 years at ABC. “He became Philadelphia, with his enthusiasm and reverence for its sports teams, institutions, politicians and working-class people.”

When Davis left Philly for New York in 2003, it was difficult. “Jim and I became good friends, but we had our challenges,” he says. “There were periods when he didn’t speak to me. Years later, I told him I appreciated the break.”

And as for vanity? Roberts remembers Gardner’s first gray spot and the consult that followed. “Cover it? Or let it happen?” they pondered.

Read more : Who Invented The Outhouse

Gardner let it happen—but only after one treatment failed. “I told him, ‘Are you kidding me?’” Roberts says. “Then he went gray naturally.”

Board president of the Radnor Township School District, Amy Goldman is her husband’s polar opposite socially. They share two children, Emily, 23, an artist in Portland, Maine, and Jesse, 21, a senior at Vanderbilt University. Jesse attended the Haverford School, where he had a breakout senior year as a baseball player, leading the team in home runs and runs batted in. “How does that happen?” muses his dad, pointing to the backyard. “That’s where he learned to play baseball, but he’d never admit that.”

Gardner also has two children from his first marriage—Josh, 34, and Jenn, 31. Josh, who works in marketing and promotions at NBC Sports, has given him his first grandchild, Henry Wells Goldman. Gardner is quick to share a photo of his year-old grandson taken at Minella’s Diner. The Wayne institution is a longtime breakfast haunt for Gardner—to the point where Roberts calls him “the king of Minella’s.”

In his double-shift days at Channel 6, Gardner would arrive at the station by 2:30 p.m. After the 6 o’clock newscast, he’d come home for dinner, then drive back for the 11 p.m. show. “I was able to do that almost every night,” he says. “It was important.”

The den is Gardner’s favorite room in the house. On its walls, there’s a framed New York Times front page from each day one of his children was born. There are photos, mostly of him interviewing recent presidents—and one with Roberts and the late sportscaster Gary Papa, who succumbed to cancer in 2009. There’s a copy of Ray Didinger’s recent book, Finished Business: My Fifty Years of Headlines, Heroes, and Heartaches, inscribed to Gardner, hailing him as “a great journalist and true Philly guy.”

Since 1987, Gardner has quietly provided an annual scholarship for one student at Temple University’s Klein College of Media and Communication. Meanwhile, the industry has changed exponentially in his half century of service. Its business model has morphed dramatically as the availability of what (and how) to watch has turned voluminous. “There’s still a firewall, a substance firewall, an integrity firewall, and we can’t let our ability to get on air dictate what should or shouldn’t be on air,” he says. “We cannot blur the lines.”

One particular aspect of the local market grates on him: the daily compulsion to report acts of violence and murder. “There’s something going on in our big cities—human life is so devalued,” Gardner says. “The last two or three years have been almost excruciating for me, but I can’t let it show. It’s just so intolerable, and you never get desensitized.”

If there’s a secret ingredient to becoming a successful local anchor, it’s empathy. “People have to like and trust you—and that’s not casual stuff,” Gardner says.

Davis recalls the fatal Senator John Heinz helicopter crash in 1991 above the Merion Elementary School playground that resulted in 10-plus hours of live Action News coverage. “At one point, Jim came into my office and said, ‘What about the kids?’” Davis recalls. “At 11, that’s what he was thinking, and that’s what he led with.”

Gardner’s lead focus in retirement will be the “risk to our democracy and threats to our country as we’ve known it—and to what we think we are.” It’s been dominating his reading. Society, he says, is in a precarious place. “There’s a lot of anger out there—a lot of insecurity—and some people in the public sphere are taking advantage of it,” he says. “I hope we don’t go off a cliff.”

Pschorr believes the long goodbye has been getting to Gardner. “He’s one of the last titans of a certain standard of news, especially among local journalists,” she says. “He’s been an icon for generations of families.”

And deep down, Gardner knows it. “I wanted to go against the grain, to stay in one place for a lifetime, to raise my children here, and to call one place home,” he says.

Back in the day, Davis would hit the streets for “unofficial audience research.” He’ll always remember what one female viewer once told him: “I never believe anything until Jim Gardner says it.”

Related: Radio Host John DeBella Celebrates 20 Years on Air With WMGK

Source: https://t-tees.com

Category: WHO