Wayfair and its colorful pinwheel logo are seemingly everywhere these days: on boxes being opened by Bobby Berk in the most recent season of Queer Eye, hovering next to photos of your middle school friends’ kids in Facebook sidebar ads. Its ubiquitous jingle — “Wayfair, you’ve got just what I need!” — is likely embedded in your subconscious.

It’s also been in the news. In June, Wayfair was the subject of protests from its employees, who walked out of the company’s Boston office to protest their employer selling children’s beds to a government contractor furnishing US border detention facilities. The breadth of coverage and attention on the issue shined a light on just how big the company is. Everyone knows what Wayfair is.

You are viewing: Who Owns Loon Peak Furniture

Or do they? Even if you’ve ordered furniture from the website, you may find yourself not entirely able to say what it … is. A brand? A marketplace? Something else entirely?

Wayfair sells more than 14 million products across five websites. It also has 80 “house brands,” which are not actually brands at all but act as a way to categorize and merchandise products into certain decorating aesthetics. It does not manufacture any of the products it sells, instead using a drop ship model. When customers place an order, Wayfair purchases the item from one of its 11,000 suppliers, which then ships to the customer, though this happens in different ways.

In 2018, it sold almost $7 billion worth of products, making about $1.5 billion in gross profit. But the company isn’t profitable, as it spent $2 billion on operating costs (more than a third of that on marketing) in the service of acquiring new customers and retaining existing ones. Still, its sales are growing every year, and it is winning over repeat customers.

The market for affordable furniture and decor is limited to a few entities and, in the Instagram era, decorating trends change faster than you can say “shiplap.” Shoppers have come to rely on retailers with huge selections like Amazon, Overstock, Houzz, and Wayfair for home decor and, increasingly, large furniture, as expectations for fast delivery become the norm. Wayfair became the behemoth it is now due to the dot-com bust of the early 2000s, the changing nature of internet shopping, and an increasingly global supply chain. It’s emerged as a leader among its peers. But for customers, it can get pretty confusing.

Wayfair’s brand and its “brands”

Wayfair is not only Wayfair.com. It also owns Joss & Main, AllModern, Perigold, and Birch Lane. Wayfair.com is the main catchall site, where you can find most of the company’s offerings, from furniture to appliances to that ridiculous one-person sauna that went viral. The other sites offer less merchandise, but they are loosely themed. AllModern is obviously modern, while Joss & Main and Birch Lane are fairly indistinguishable and lean traditional. The newest site, Perigold, is high-end, though it seems to be geared specifically toward someone who owns a castle and/or a villa. (This $27,000 twin marriage bed set — marked down from $32,000 — seems ready-made for The Crown.) The company calls these sites “lifestyle brands.”

Beyond the “lifestyle brands,” the products are further grouped into one of Wayfair’s 80 so-called house brands, which are only sold on Wayfair.com. “The point of our brands is to curate this massive selection and to create an environment where you’re able to understand what the style is. [It’s] to make the shopping experience easier,” says Jon Blotner, Wayfair’s head of private label, visual media, and new suppliers.

There is Loon Peak, Bungalow Rose, Laurel Foundry Modern Farmhouse, Winston Porter, Andover Mills, Brayden Studio, Breakwater Bay, Lark Manor, Millwood Pines, Gracie Oaks, and Beachcrest Home, all of which sound like they were created by a name generator. The latest, announced just days before the walkout, is called Hashtag Home. It’s colorful and, as the name suggests, social media-friendly.

According to a Wayfair earnings call in May, more than 70 percent of its sales come from its house brands. The remainder of sales are items that have not been folded into a house brand umbrella. For example, you can find Safavieh rugs there sold under the Safavieh name. To further confuse things, though, Safavieh also provides items to Wayfair that end up in a house brand category.

I bought two house-brand “Breakwater Bay Peralez” bedside tables and they arrived in Safavieh boxes. Nowhere on the listing does it say they’re manufactured by Safavieh. When you click on the Breakwater Bay “brand” page, it’s described like this: “Whether you’re stationed seaside or living inland, Breakwater Bay brings nautical style to any space.” This is all great for Safavieh, which can sell its products in a variety of settings, as Safavieh president Arash Yaraghi explained to me. The company has name recognition, so Safavieh can sell things to people looking for Safavieh as well as people looking for vaguely nautical bedside tables and don’t know or care who manufactured it.

Read more : Who Won The Pendleton Xtreme Bulls Last Night

With traditional retailers, house brands, also called private labels, are usually manufactured by an outside company and then packaged and merchandised to look like a real brand. The store gets higher profit margins and customers get cheaper prices than with outside name brands. When you order something from Threshold, a house brand at Target, it comes in a Threshold box with Threshold labeling and a specific look. It’s all consistent. “It’s important that packaging leads the customer journey,” says Anika Sharma, an adjunct assistant professor at NYU Stern and a marketing professional.

That’s not the case with Wayfair’s house brands. All these brands feature proprietary digital photo treatments to make them appealing and more easily shoppable, but once you order it from the pretty digital page it’s on, the branding stops. Wayfair doesn’t care if you remember something came from Breakwater Bay or Bungalow Rose. “We always want people to say [it came from] Wayfair,” says Blotner. “Do I think in the future people will say Bungalow Rose is a great brand? Maybe, but what I really want customers to say is, ‘Man, it is so much easier to shop at Wayfair.’”

One item, many names and prices

It would be tempting to compare these “lifestyle brands” and “house brands” to those of a company like Williams Sonoma Inc., which owns Williams Sonoma, Pottery Barn, and West Elm. But it’s not exactly analogous. William Sonoma, Inc.’s brands are all distinct stores with their own aesthetic and their own merchandise. While perhaps the same manufacturers might make furniture for both stores, you’re not going to find the exact same table at Pottery Barn and West Elm, or find those products at any other retailer. This is not true of Wayfair and its sites, which offer some of the same products. Those products can often be found on competitors’ sites as well, often at different prices.

“The vast majority of Wayfair’s products come directly from factory or importer warehouses. Wayfair buys it from an intermediary that got it [to the US], and then in many cases, that intermediary also ships directly to the consumer’s home,” says Jerry Epperson, a furniture industry analyst. (This is starting to change as Wayfair sets up its own warehousing system called CastleGate to help suppliers get things to customers quicker.) At its heart, Wayfair uses a classic drop ship model and holds no merchandise of its own.

Wayfair decides what merchandise to sell and sets the prices on everything, just like any traditional retailer does. The money you pay for, say, my “Breakwater Bay” tables goes directly to Wayfair. But then Wayfair buys the tables at a lower, previously agreed-upon price from the supplier — in this case, Safavieh.

Quartz first reported on the phenomenon of one item with many names and prices in 2017. Any retailer can buy from the same suppliers, since none of the designs are exclusive. And outside of a few brands like La-Z-Boy, consumers really don’t know furniture brands, according to Epperson. So sellers can brand them however they want. (Much like Zara and fashion, you can also find knockoffs. For example, this Pottery Barn leather table sells for $1,200; there is a similar one on Wayfair for $285.)

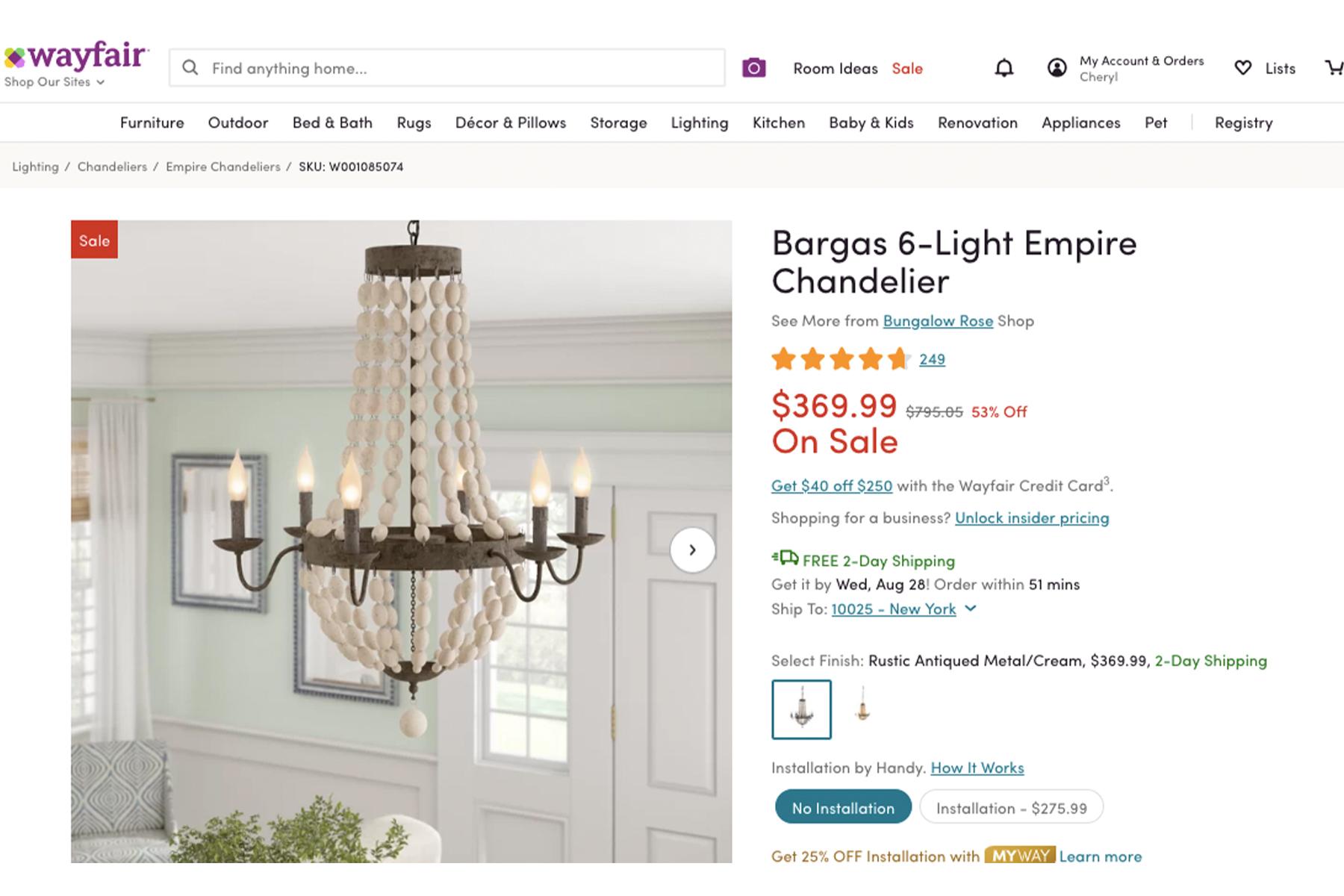

Here’s what this looks like: On Wayfair.com, a rustic, wood-beaded light fixture is called the Bungalow Rose Bargas 6-Light Empire Chandelier and is depicted with multiple images in several settings, for $369.99. But it’s also available on JossandMain.com, one of Wayfair’s lifestyle brand sites, as the Bargas 6-Light Empire Chandelier, with only one accompanying photo. As of this writing, it costs $359.99. At one point I saw them listed at slightly different prices, $359.99 and $362.77, respectively. I also did a Google image search and found the same chandelier at AntiqueFarmhouse.com for $368 and at Target for $556, with different names.

Pricing on Wayfair’s sites change in real time, thanks to an automated algorithm. In a 2015 Harvard Business School case study, Wayfair’s vice president of pricing at the time told authors Thales Teixeira and Elizabeth Anne Watkins that prices are adjusted daily: “On any given day our model evaluates factors such as seasonal effects and competition, and adjusts prices automatically.” The algorithm also takes into consideration availability and shipping times. Wayfair’s Blotner said this is common across e-commerce platforms. “All e-commerce has dynamic pricing. It’s standard.”

How Wayfair grew out of the early-’00s dot-com bubble

In the late ’90s, as the internet became more and more accessible to the average consumer, e-commerce businesses were all the rage, garnering huge investments from venture capitalists. Remember Pets.com? At the apex of its popularity, its sock puppet commercial aired during the 2000 Super Bowl. But it never turned a profit, like many of its contemporaries, and it had to shutter. This was a familiar tale during the end of the dot-com boom, and by spring 2000, the bubble burst, crashing the Nasdaq and leaving many dead companies in its wake. It was in this hostile environment that Wayfair founders and former college friends Niraj Shah and Steve Conine decided it would be a good idea to launch an e-commerce business.

They came across a bunch of mom-and-pop, non-tech-savvy businesses selling things like birdhouses online. The owners made a decent living doing so, but Shah and Conine saw a bigger future for this sort of product specificity, according to a 2012 Inc. profile of the company. And they chose furniture and home furnishings because it was something not many retailers were doing online at the time.

One of their first sites was called RacksandStands.com, which sold, yes, racks and stands for TVs and stereos. They used a drop ship model even back then, selling thousands of products from multiple manufacturers. They used search engine optimization data and targeted keyword ads to eventually build more than 240 separate sites like EveryMirror.com, playing into the terms people were searching for the most. They called their company CSN Stores, avoiding clever digital-sounding names in order to not immediately scare away furniture suppliers they met who were nervous about online businesses.

Then in 2011, their sites started getting less traffic, due to changes in Google’s search algorithm, according to DigitalCommerce360. Customers also weren’t return purchasers on the sites since they were stumbling onto them via generic searches rather than out of any sense of brand or retailer loyalty. After all, how often do you need to buy a stereo stand? So the founders combined all its sites and rebranded as Wayfair. To publicize this, it sent its 700 employees out on a pub crawl in Boston, all wearing their new Wayfair T-shirts.

Read more : Who Makes Kirkland Pinot Grigio

It took over a year for Google to start surfacing the company regularly in searches. In 2012, Wayfair paid for its first TV commercial, which was colorful and whimsical, and featured a narrator reading a poem about the large and small things you could buy there. The company hired a former Better Homes and Gardens editor for input on building a visually appealing site. The infamous jingle debuted in 2014, the same year the company went public. According to the Harvard case study, after the ads started airing, the company saw an uptick in Google searches for “Wayfair.”

The growth was further fueled by a savvy use of targeted marketing on Google, Facebook, Instagram, and via customer emails. To consistently show up at the top of Google when someone searches for something, the company (like all large e-commerce sites) likely bids on Google ad keywords, says Kirthi Kalyanam, the director of the Retail Management Institute at the Leavey School of Business at Santa Clara University and a former board member at Wayfair competitor Overstock. Generally, if two companies bid on the same keywords, like “velvet sofa,” Google will award the most prominent ad placement to the highest bidder. Google gets paid when someone clicks on the ad, though, so it also takes into account the likelihood that someone will click.

At this point, Wayfair may bid less on the phrase “rustic chandelier,” but more people recognize it than they do AntiqueFarmhouse.com at this point and will be more likely to click. And it all builds from there. The more people who click on and purchase from Wayfair, the more frequently it will show up in organic, non-paid searches.

The future of Wayfair

Epperson, the furniture industry analyst, estimates that “fully assembled furniture” is likely less than a sixth of what Wayfair sells. It’s easier to ship smaller decor items or home improvement supplies. And Wayfair has said on earnings calls that its average customer purchase is about $250. But it’s definitely trying to grow its large furniture business, while also getting you to shop there for hooks and dish towels. “Wayfair has tried since the beginning to differentiate itself from Amazon by selling big furniture that Amazon has historically avoided,” says Teixeira, the professor of the Harvard case study and author of Unlocking the Customer Value Chain.

After doing a series of pop-ups through the years, Wayfair just opened its first permanent store in Natick, Massachusetts. It offers hundreds of smaller items that customers can take home with them, and also will allow customers to get an IRL taste of what its digital services are like. Customers can work with designers to plan out rooms and touch fabrics that it uses in a furniture customization program.

But the employee walkout still leaves lingering questions and shines a light on the furniture industry as a whole. Its biggest players, including Ikea and Amazon, are rife with questionable labor practices, fuzzy supply chains, and a negative environmental impact, as Kate Wagner recently wrote at Curbed. Consumers who want to shop ethically are faced with trying to untangle a byzantine selling structure.

Ross Steinman, a psychology professor at Widener University who studies brand transgressions, did not think the walkout would be good for Wayfair when I called him right after it happened in June. (A brand transgression is something like the BP oil spill or Kendall Jenner’s Pepsi ad.) But he acknowledged that, similar to Amazon, it’s a difficult company to boycott because of its sheer size, ubiquity, and customer loyalty. “What often happens with brand transgressions is, despite everyone’s claims, [customers] do come back,” he says. “From a marketing perspective, Wayfair’s brand mishap has mostly washed away due to a rapid media cycle that has moved on to the next big story.”

Whether Wayfair can disentangle itself successfully may ultimately depend on how it responds to its employees first and foremost. CEO Shah acknowledged to investors on the August 1 earnings call that leadership was still working with employees on the issue. “We have an ongoing dialogue with our employees and are proud to have a terrific team that is passionate and engaged, both at work and in their broader communities,” he said. “We’re committed to constructively working together with Wayfairians all over the world, to internally navigate this and other important topics that may arise in the future.”

While some Glassdoor reviews paint a picture of low pay and some systemic disorganization, employees I spoke to seemed to be happy at Wayfair.

“My day-to-day life there is fun, I enjoy the job, it is professionally encouraging me to grow,” says one current employee, who didn’t want to discuss the walkout aftermath and asked for anonymity because Wayfair has been messaging its displeasure with employees speaking to the press since the walkout.

“I do think Wayfair is a strong brand and has significant brand equity,” says Steinman. “Without a sustained effort by the employee group, or a consumer activist group that adopts the cause, it is likely that Wayfair’s consumers will continue to purchase their products as they have in the past.”

Sign up for The Goods’ newsletter. Twice a week, we’ll send you the best Goods stories exploring what we buy, why we buy it, and why it matters.

Source: https://t-tees.com

Category: WHO