The Great Fear (French: la Grande Peur) was a wave of panic that swept the French countryside in late July and early August 1789. Fearful of plots by aristocrats to undermine the budding French Revolution (1789-1799), peasants and townspeople mobilized, attacking manorial houses. The unrest contributed to the passage of the August Decrees, which abolished feudalism in France.

The Great Fear and its associated riots only lasted for roughly three weeks but set the stage for some of the most important developments of the Revolution. French historian Georges Lefebvre proposed some possible causes of the Great Fear being the breakdown in communication due to unrest in Paris, high tensions set off by food shortages and widespread unemployment, and fears of violent retaliation by the nobility and foreign powers meant to undermine the people. Other historians have argued that one possible cause could be the peasants’ consumption of ergot, a hallucinogenic fungus.

You are viewing: Why Did The Great Fear Happen

Hunger & Despair

Lefebvre opens his 1932 book The Great Fear of 1789, still regarded as the seminal work on the topic, with a quote from French critic Hippolyte Taine: “The people are like a man walking in a pond of water up to his mouth: the slightest dip in the ground, the slightest ripple, makes him lose his footing – he sinks and chokes” (Lefebvre, 6). Taine’s quote wonderfully illustrates the precarious position of the French lower classes in the Ancien Régime. Even in the best of times, one poor harvest could mean disaster for the farmers and industrial workers alike.

Since the late 1760s, harvests had become increasingly uncertain, and yields fluctuated sharply. Partly resulting from the 1783 Laki eruption in Iceland, harvests across France became progressively worse, reaching a low point in 1788, when summer hailstorms killed many crops, and a subsequent August draught killed much of the rest. For urban workers, this meant bread prices skyrocketed, and by 1789 the poorest were spending up to 80% of their income solely on bread.

Unemployment also rose sharply, with 8-11 million people, or roughly a third of the population, either unemployed or lacking other forms of support. France’s rapidly growing population, having increased by 2-3 million since 1770, added to the strain on resources. In one of their cahiers, or grievances, written before the Estates-General of 1789, the villagers of La Caure succinctly described the population problem by writing, “the number of our children plunges us into despair” (Lefebvre, 9). While many flocked to the cities looking for jobs, lots of people also flooded the countryside, desperate to find work on farms. However, by the late 18th century, many peasant farms were barely large enough to support even a single family. Due to the practice of splitting the land evenly amongst sons upon inheritance, many farmers were left with minuscule and often unfertile tracts of land. This led many landless peasants to seek work on the large farming estates owned by the nobility. Since these grand estates were often only able to provide work in the harvest season, laborers suffered in perpetual poverty the rest of the year.

Many of the landless and unemployed people who flooded the countryside were unable to find work, forcing some to turn to begging. Travelling from farm to farm, often in groups, these vagrants would ask for crusts of bread or places to sleep for the night. While some farmers were sympathetic, many others were distrustful or outright fearful of them. Word began to spread that bands of vagabonds were knocking down fences or setting fire to farmers’ fruit trees after being denied help, while some vagrants were allegedly swarming cornfields and cutting down unripe stalks of corn, threatening another year’s harvest. Some farmers nervously wrote to nearby towns, asking for soldiers to be sent to protect their fields, while others blamed the church for not providing for the impoverished with the money collected from tithes.

Salt smugglers took advantage of the countryside chaos by travelling from farm to farm, bullying and terrorizing farmers into buying their contraband goods. These smugglers would often be followed by the gabelous, the hated tax collectors contracted by the French government. The gabelous were often little better than thugs themselves and would beat and rob farmers suspected of purchasing black market salt, occasionally even hauling them off to jail. Meanwhile, as towns erupted into bread riots, townsfolk also made expeditions out to farms where they forced farmers to sell them their goods.

The paralysis of royal authority following the rise of the National Assembly and the Storming of the Bastille meant that farmers could not rely on police or soldiers. In the spring and summer of 1789, many began to arm themselves and look to one another for protection. By July, farmers had banded together to defend their villages, with some even standing guard at roads or bridges for weeks at a time. However, many of the reports of violence were merely the result of rumors. As reliable news from Paris became less frequent because of the revolutionary excitement occurring there, rumors in the countryside increased in intensity; one such story told of the residents of Lyons fighting off hundreds of brigands which included marauding Savoyards and escaped galley slaves. Another tale told of a British squadron of warships haunting the channel, waiting for brigands to invade the port city of Le Havre and throw open the gates to them. As these rumors heightened tensions, many looked for a more tangible enemy to blame and found one in the clergy and aristocracy.

Conspiracies & Malcontents

Read more : Why Did Beckham Leave Man United

Many across France had long blamed the privileged classes for plotting against them. Stretching back to at least the time of the Flour War, a major bread riot that swept the Paris region in 1775, the conspiracy theory known as the Pacte de Famine began to gain traction. Subscribers to this theory believed that the bad harvests and food shortages plaguing France had been orchestrated by the nobility in order to better subjugate and control the people. They allegedly achieved this by hoarding foodstuffs in monasteries and in their manorial castles. Whether or not King Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792) was involved in the conspiracy remained a point of division; some believed he was a benevolent king being tricked and misled by his devious ministers, while others thought he was the mastermind behind the whole plot.

Evidence for some kind of upper-class plot appeared to sprout in the early summer of 1789, as the proceedings of the Estates-General began to turn in favor of the Third Estate, which proclaimed a National Assembly on 17 June. By 1 July, the king had summoned 30,000 soldiers to the Paris region, many of them foreign troops, and on the 11th, he dismissed his chief minister, Jacques Necker, seen by many as one of the primary defenders of the people. These acts appeared to be counter-revolutionary measures, taken to thwart the National Assembly and kill the Revolution in its crib. Riots in Paris led to the Storming of the Bastille on 14 July, and although the king withdrew the troops and reinstated Necker, the seeds of distrust had been planted.

On 16 July, the Comte d’Artois, the king’s youngest brother and one of the most outspoken enemies of the Revolution, fled Versailles along with a large entourage of relatives and supporters. It was unknown where he had gone; some believed he had fled to Spain, others Turin. But it was widely believed that Artois would soon return to France at the head of a foreign army. There was no shortage of enemies of the Revolution who would be willing to give him one, after all. The kingdoms of Spain, Naples, and Sicily were all controlled by the Bourbons, while the Holy Roman Emperor was the brother of Queen Marie Antoinette (1755-1793).

Across France, towns began arming themselves by calling up defensive militias, pledging to defend the National Assembly from any threat, foreign or domestic. In Montpellier, every male of fighting age except for priests and monks was ordered to prepare to take up arms, while the small town of Orgelet in the Jura wrote to Versailles and promised to “sacrifice their peace, their possessions, everything down to the last drop of blood” to defend the Assembly (Lefebvre, 81).

Anger against the nobility only intensified after Artois’ flight. On 16 July, citizens of Le Havre stopped shipments of grain and flour from being sent to Paris, for fear that they would be used to feed royal troops. The same day, a citizens’ militia in Dijon seized the chateau and armories, imprisoned their military governor, and confined all nobles and clergy to their homes. Members of the ministry that was to have replaced Necker’s government were harassed, imprisoned, or in some cases brutally murdered: in Paris, the mouth of the severed head of one minister, Foulon, was stuffed with grass to signify his alleged involvement in the famine plot.

As paranoia took hold in many towns, revolutionary cockade wearing became compulsory, with those commoners who were judged hostile to the people’s cause forbidden from wearing one. Around this time, it became commonplace, when meeting a new person, to ask, “Are you for the Third Estate?” (Lefebvre, 88). Although the Great Fear gained momentum in the towns of France, it would reach its apex in the countryside, where its target was not individual nobles but the system of feudalism itself.

Panic & Revolt

Already on edge from the rumors of violent bandits, countryside peasants had been watching events in Paris closely. The actions of 14 July and the subsequent arming of townships only confirmed their suspicions that there was indeed an aristocratic plot against them. Yet many of these peasants had even greater reason to believe they were in danger than the townsfolk did. As farmers, many of them paid feudal dues to local seigneurs and knew their lords’ nature well enough to understand they would never willingly give up their privileges. Furthermore, those peasants with knowledge of history understood that most previous uprisings against feudal lords had ended in bloodshed. With this perspective, the peasants realized they were in danger as soon as the Estates-General had been summoned.

It was only natural, therefore, that rage was turned toward the lords who were, even in this period of famine and financial difficulty, “ever busy sucking their blood” (Furet, 75). The tipping point was reached on 19 July, when an explosion destroyed the Chateau de Quincey, home of one of the more hated landlords in the Franche-Comté region, killing five people and injuring several others. The explosion, while likely an accident caused by a drunken dinner guest stumbling too close to a powder keg with a flaming torch, nonetheless alarmed the peasants, who believed the nobility would use it as an excuse to crack down on them.

Read more : Why Do Swim Trunks Have Mesh

Immediately after the explosion at Quincey, the peasants of Franche-Comté arose in revolt. Bands of armed peasants invaded seigneurial estates, breaking into barns and reclaiming the goods they had paid in manorial dues. Muniment rooms, which contained records of feudal obligations, were ransacked and torched, and other symbols of feudalism such as wine presses and mills owned by nobles, were likewise attacked. In some cases, the chateaux themselves were invaded and plundered. If the local seigneur happened to be in residence during the attack, he would likely be accosted by the peasants who would force him to renounce his feudal privileges. Abbeys and monasteries, too, were raided in search of hoarded goods, and entire parishes banded together to refuse to pay their tithes.

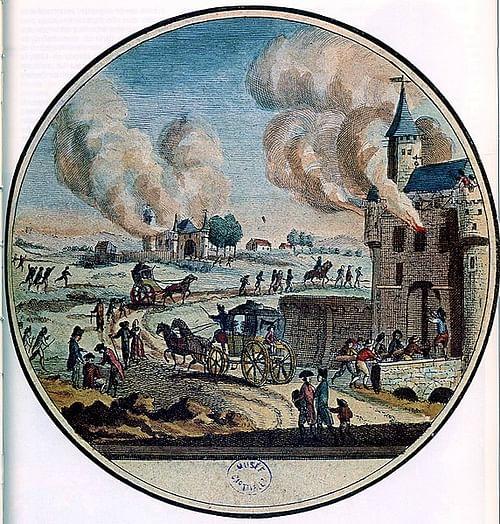

The Franche-Comté riots were eventually subdued by detachments of cavalry, but the Great Fear had already caused similar revolts to break out all over the country, most significantly in the regions of Hainault, Alsace, Normandy, and the Mâconnais. In the last weeks of July 1789, bands of peasants harassed nobles and raided their estates. Carriages were pushed into rivers and nobles were harassed, humiliated, and, in some cases, beaten. Despite this, it is generally agreed that the countryside revolts during the Great Fear were relatively bloodless, and murders were few and far between. A few chateaux were burned or razed to the ground, as was the case with an estate owned by the Talleyrand family, but this too was rare.

Many of the peasants claimed to be acting on behalf of the king, who had recently accepted a revolutionary cockade and was perceived by some to be in favor of the Revolution. In the Mâconnais, an official claimed that he had seen a letter in the king’s name that authorized “all the people in the country to enter all the chateaux of the Mâconnais to demand their title deeds and if they are refused, they can loot, burn and plunder; they will not be punished” (Lefebvre, 96). On 21 July, residents of Strasbourg and Cherbourg refused to pay the market price for bread, claiming that the king intended all his subjects to be equally provided for. Just as seigneurial estates were raided in the countryside, houses of those believed to be thwarting the king’s will were also attacked in the towns.

As the name suggests, the Great Fear was a period of mass hysteria. As the chaos of the Revolution had begun to cause gaps in communication, it was difficult to know which news was true and what was fake. Tales were told of British and German mercenaries burning the countryside, while witnesses swore that they had seen Artois return from Spain with a 50,000-man army at his back. The brigands who had supposedly started the havoc were believed to be agents in the pay of British Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger, while English traveler Arthur Young was told by Frenchmen he had believed to be “otherwise quite intelligent” that Queen Marie Antoinette was planning to poison the king and replace him with Artois, rumored to be her lover (Schama, 436).

The sight of smoke emanating from the peasants’ raids on nobles’ properties convinced other peasants that they were under brigand attack, adding even further layers to existing fears. Scholar Simon Schama tells an anecdote of no less than 3,000 men in southern Champagne arming themselves to drive off a band of bandits, only to discover upon closer inspection that what they thought had been a group of dangerous thugs from a distance was nothing more than a herd of cattle (432).

End of the Fear & Legacy

By early August, the National Assembly had decided it was not in their best interests to have bands of panicked peasants roving the countryside. To restore calm to the provinces, the Vicomte de Noailles put forth the radical idea of abolishing the privileges of the nobility. This idea would lead to the passage of the August Decrees on the night of 4 August, which dismantled feudalism in France and abolished the Gallican Church’s right to collect tithes. The August Decrees were monumental and, combined with the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen that came soon after, were some of the most significant achievements of the entire Revolution. The decrees also seemed to placate the countryside; as abruptly as it had begun, the Great Fear had mostly fizzled out by 6 August.

Although most peasants who had participated in the revolts returned to their homes, large numbers had either been arrested during the unrest or at some point shortly afterward. In most places where the revolts had ended on their own, few people were sentenced. However, in areas like Alsace, Hainault, and Franche-Comté, where the military had ended the riots, many peasants were hanged or sentenced to service as galley slaves.

The Great Fear was, in conclusion, a puzzling moment in the history of the French Revolution, having long confused historians with its bizarre nature. Although peasant revolts were hardly a unique phenomenon, the Great Fear stands out due to both its scope and its brevity; barely lasting three weeks, the unrest enveloped large portions of French towns and the countryside. It was predicated almost entirely on rumors or exaggerated stories, turning bands of wandering beggars down on their luck into fearsome brigands in the pay of foreign powers. If such groups of marauders indeed existed, they were certainly not large or threatening enough to justify the panic that set in; and yet the panic caused by a mostly imagined threat led to the abolition of one of the most ancient institutions in France.

The seeds of distrust planted by the Great Fear lasted far longer than the event itself. Some of the nobility and clergy became further embittered toward the Revolution for the destruction of their privileges. Meanwhile, although the countryside unrest ended, the general fear remained. Hunger was still prevalent, and the threat of foreign intervention in the Revolution was ever-looming. Of course, these latter fears would eventually be realized when, in the course of the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802), France found itself at war with most of the rest of Europe.

Source: https://t-tees.com

Category: WHY