Record-setting rainfall in 2018. A month’s worth of water that drenched Northern Virginia in an hour in July 2019. Neighborhoods that flood repeatedly in Richmond’s Southside and Petersburg.

In Virginia, conversations about climate change have tended to focus on sea level rise, the waters that surge up from oceans and coastal rivers to overspill their traditional bounds. But climate change isn’t just driving waters up. It’s also driving them down, increasing precipitation — and especially the intensity of precipitation — throughout the commonwealth.

You are viewing: Why Is It Raining So Much In Virginia

“Broadly across Virginia … there seems to be a consensus that there is more water around, and that the storms are heavier and they dump more water when they come, and that’s a problem,” said Ann Phillips, the state’s special assistant to the governor for coastal adaptation and protection. “And that impacts people not every day, but often enough.”

Climate change is affecting precipitation globally, but the impacts aren’t uniform everywhere. Rising global temperatures in some cases are leading to increases in drought, as has been apparent in the western U.S. Overall, the most recent report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which was approved by all 195 member states of the United Nations, found that precipitation over land “has likely increased since 1950, with a faster rate of increase since the 1980s.”

Even more critically, though, the hundreds of scientists who contributed to the IPCC report found that climate change is leading to jumps in the frequency and intensity of heavy precipitation — a trend likely to continue as temperatures warm.

“It is very likely that heavy precipitation events will intensify and become more frequent in most regions with additional global warming,” the report concluded. “At the global scale, extreme daily precipitation events are projected to intensify by about 7 percent for each 1°C of global warming.”

Those patterns are also being seen in Virginia, scientists say.

“We know rainfall patterns are changing — more intense, more frequent storms,” said Jonathan Goodall, an engineering professor at the University of Virginia who co-chaired a recent study for the General Assembly on climate change impacts in Virginia, during a presentation to the Joint Commission on Technology and Science earlier this week. “Those aren’t limited to the coast. Those will happen across the commonwealth.”

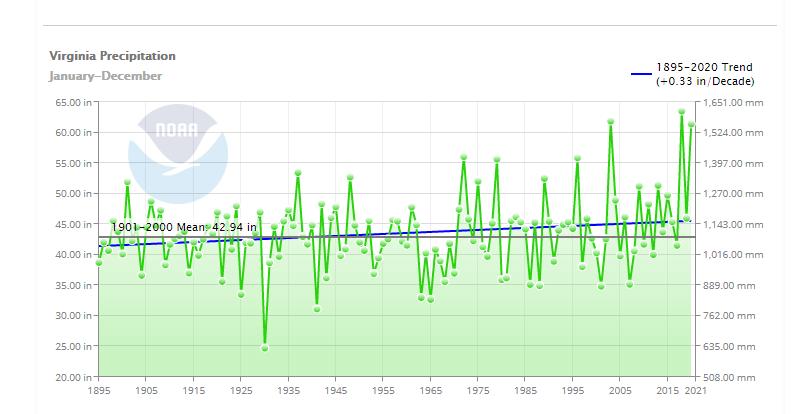

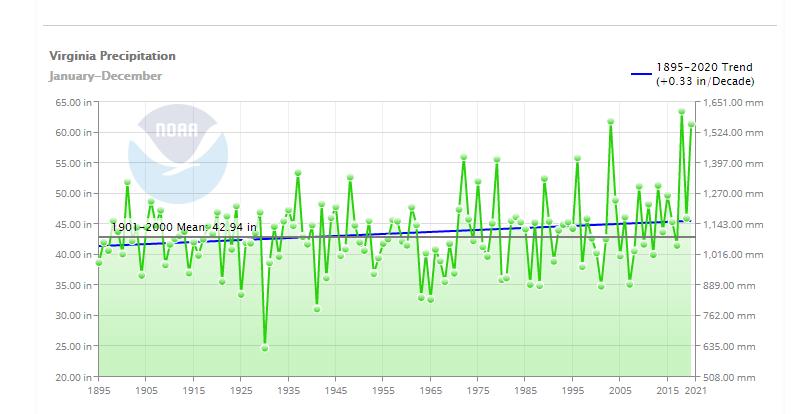

Time series data from the National Centers for Environmental Information, which operates within the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, show a trend of increasing precipitation in Virginia since 1895.

In a more localized study that examined data from 43 locations across Virginia between 1947 and 2016, researchers Michael Allen and Thomas Allen (no relation) at Old Dominion University found that both average annual precipitation and heavy rainfall frequency increased statewide.

“Heavy rain events are increasing pretty uniformly across the commonwealth,” said Michael Allen. “We often think in Virginia of flooding as a coastal phenomenon, where the reality is a lot of our flooding has taken place in non-coastal areas.”

Read more : Why Are Axolotls Illegal In California

Jeremy Hoffman, chief scientist at the Science Museum of Virginia, said that precipitation increases are “pretty much ubiquitous across the commonwealth” but will vary depending on the season.

“The biggest precipitation changes have been that our fall and spring have gotten relatively rainier or at least relatively wetter at the expense of our summer,” said Hoffman.

Increasing unpredictability in precipitation is also likely to characterize the future, with consequences for not only infrastructure but also patterns of living, working and traveling.

“Because we’ll switch between these longer drier periods interspersed with these deluge conditions, that becomes really hard to manage,” Hoffman said.

Overwhelmed infrastructure

In some neighborhoods of Richmond’s Southside, the struggles of managing increased and more intense rainfall are already apparent in frequent flooding that leaves streets and yards waterlogged for days.

“This is the type of flooding that happens in certain parts of Southside every time it rains,” said Amy Wentz, co-founder of local nonprofit Southside ReLeaf, which works to reduce environmental disparities as the climate changes. “Flooding is one of the big things we’ve heard from our community members that they’d like the city to address.”

Infrastructure statewide, whether for stormwater, roads or dams, has been designed and engineered to withstand rainfall patterns that increasingly no longer exist.

“The challenge is if the infrastructure was built and put in place 50 years ago assuming certain properties of extreme rainfall events and certain probabilities … and now we have a different reality, it will be overwhelmed,” Goodall told lawmakers on the joint commission earlier this week.

Most pressing to the state is the need to update the rainfall projections on which federal engineering standards are based, a set of data collected by the National Weather Service known as Atlas 14 that for Virginia has not been revised since 2006.

“That is the federal standard upon which stormwater infrastructure is based,” said Phillips. “Updating that data is critically important.”

State and local officials have known for a number of years that the existing Atlas 14 projections were lowballing rainfall. A 2018 report by engineering firm Dewberry for the city of Virginia Beach found “a robust, statistically significant increase in heavy rainfall not only in the immediate area but also in the region” and recommended the city increase its rainfall intensity design standards by 20 percent. Similarly, research by the Virginia Transportation Research Council found consistent bumps in rainfall and intensity statewide, leading the Virginia Department of Transportation in 2020 to order that “a 20 percent increase in rainfall intensity and a 25 percent increase in discharge shall be used in design of bridges.”

Read more : Why Was Hannah Brown On Bip

“We have seen an uptick in the intensity of” rainfall events, said Robert Carey, chief deputy commissioner of VDOT. “Traditionally, that has not been the kind of information that was necessary to be updated frequently.”

Today, that’s no longer true. Culverts, curb inlets, tunnels and other stormwater infrastructure VDOT designs, builds and maintains are being required to handle larger volumes of water in shorter amounts of time.

“It’s intensity, it’s amount, and it’s duration” that are important, said VDOT engineer Chris Swanson. “They’re all taken into consideration.”

Cities, towns and counties face the same dilemma. In coastal jurisdictions, sea level rise can exacerbate the problem: in Norfolk, standing water in the stormwater system means that “the system’s ability to drain streets after a rainfall has been curtailed by as much as 50 percent in some areas.”

Overwhelmed systems can also trigger a cascade of other problems. In Richmond, Alexandria and Lynchburg, where century-old combined sewer systems channel stormwater through the same pipes that carry wastewater, high-intensity rains can lead to overflows of raw sewage into waterways. The cities and the state have poured hundreds of millions into fixing the situation, but remaining costs total more than $1 billion. Norfolk’s struggling stormwater system has “led to more frequent road closures and exposes infrastructure not designed for frequent inundation to general deterioration and corrosion,” the recent report on Virginia climate change impacts led by Goodall noted.

As Virginia begins reworking its infrastructure to accommodate the changing landscape, two tools will be critical. In 2020, the National Weather Service put forward a proposal for updating the Atlas 14 precipitation estimates for not only Virginia, but Delaware, Maryland and North Carolina. Phillips said the work will start sometime this fall, at a cost to the commonwealth of $405,000, all of which is being funded by VDOT and the Department of Environmental Quality.

Separately, research funded by the Chesapeake Bay Trust released this year has also sketched out new projections of rainfall intensity, duration and frequency throughout the bay watershed — and, at the request of the commonwealth, the entire state of Virginia.

“This will be tremendously helpful for the commonwealth,” said Phillips. “If you only do the bay watershed, you lose a third of the state.”

Still, updated rainfall projections are only part of the picture as Virginia adjusts to a wetter, less predictable future. As Wentz of Southside ReLeaf cautioned, historic inequities have in many places led to a lack of infrastructure investment in low-income and minority neighborhoods, compounding problems found statewide.

“You can sort of tell where the neglect is happening, because that’s where the flooding is happening,” she said.

The fixes will be expensive, she acknowledged. But without them, the effects will continue to be far-reaching.

“It affects homes. It affects communities. It affects businesses,” she said. “Stormwater issues can disrupt networks, vital services or resources. It’s not just only economic losses, but it also brings a lack of quality of life.”

Source: https://t-tees.com

Category: WHY