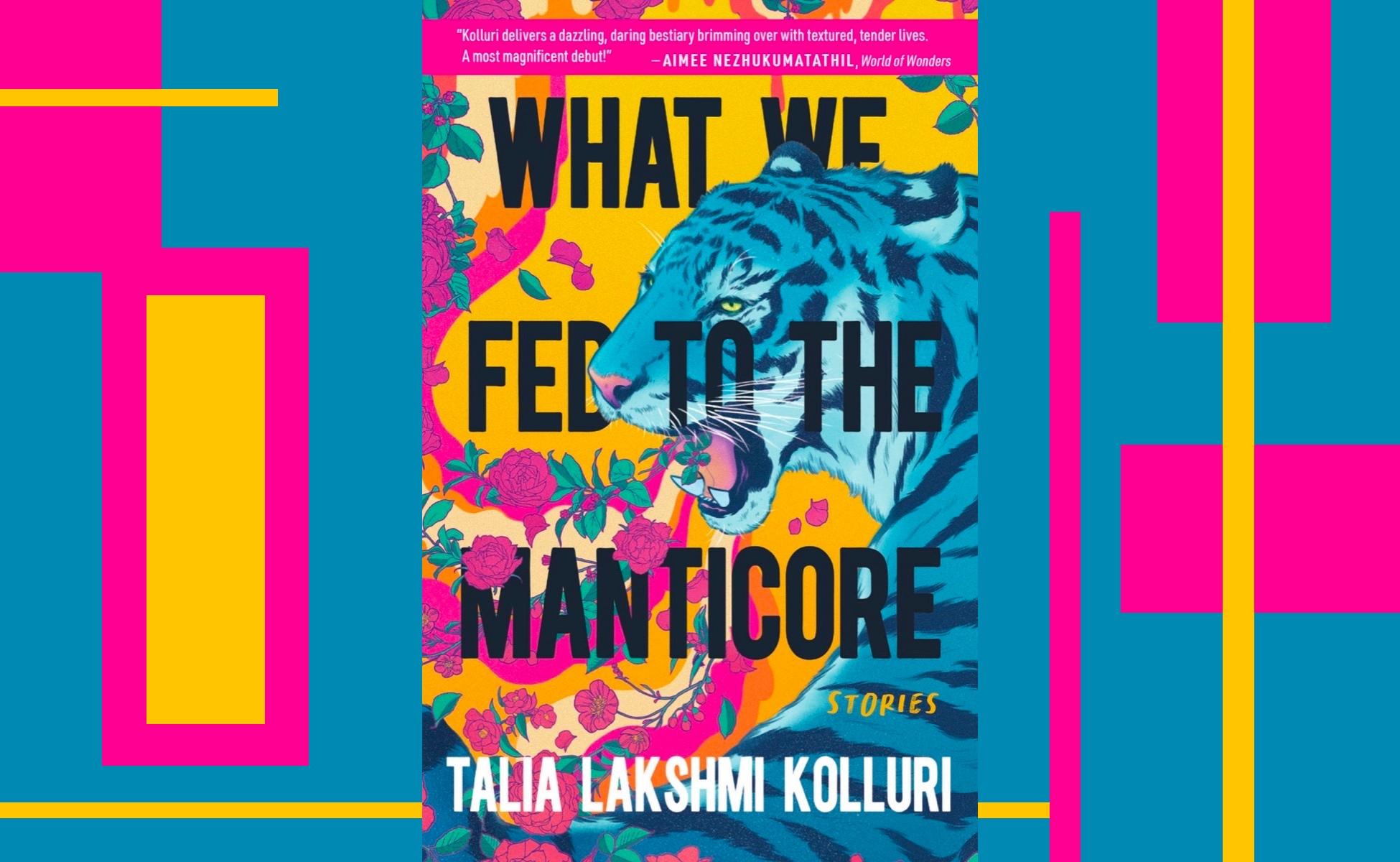

What would it feel like to understand tigers, donkeys, wolves, and even vultures? What would happen if we felt what they felt? In her debut collection What We Fed to the Manticore, Talia Lakshmi Kolluri closes the gap between us—the human readers—and nature. The skins of animals are pulled over our bodies, and we begin to see through their eyes as they use human emotions to experience events, some as expansive as war and others as individual as the loss of a friend.

What would it feel like to understand tigers, donkeys, wolves, and even vultures? What would happen if we felt what they felt? In her debut collection What We Fed to the Manticore, Talia Lakshmi Kolluri closes the gap between us—the human readers—and nature. The skins of animals are pulled over our bodies, and we begin to see through their eyes as they use human emotions to experience events, some as expansive as war and others as individual as the loss of a friend.

Grief, loneliness, loss, anger, and hope: these familiar emotions are embodied by the animals in these stories, making them beings we can empathize with. In “The Good Donkey,” a donkey and its keeper struggle to find joy in a city besieged by missiles and caged in by borders. In “The Dog Star Is the Brightest Star in the Sky,” the only polar bear in a seemingly infinite stretch of desolate arctic landscape sadly reflects on lost family. In “May God Forever Bless the Rhino Keepers,” a hound acts on unadulterated rage as it lunges at the poacher that took the life of its beloved rhino friend. We normally categorize animals as less-than-human and as creatures with limited emotional capacities, but here, we are asked to put aside this hierarchy we have created. At one point, the donkey even speaks directly to us, framing its human emotion as something it may understand better than we do. “Let me tell you a thing about tragedy,” it says.

You are viewing: What We Fed To The Manticore

“I hope that by reducing that [emotional] distance between humans and the rest of the natural world, I can remind readers that we too are part of nature,” Kolluri says in an interview with Caitlin Rae Taylor in the Southern Humanities Review. Through empathy, we grow closer to nature, and this reduced distance not only makes animals feel more human, but also makes us feel more animal. We are reminded that there is perhaps very little distinction between what is “human” and what is “animal.”

#

Read more : What Happened To Scooter From The Cambridge Hotel

Even as these boundaries are blurred, Kolluri is careful to decenter humanity, creating deliberate distance whenever the animals are forced to contend with the destruction humans have wrought on the natural world. These stories are blatant in their depiction of climate change and disregard for life. Super storms, melting ice caps, extreme heat waves, and other disasters stemming from human ruination threaten to swallow the earth with the same forceful consumption of a monstrous Manticore, a mythological beast with the head of a man, the body of a lion, and the tail of a scorpion. One image of saiga antelope that have succumbed to a sickness brought about by a warming planet, seen through the eyes of a vulture, is particularly harrowing:

[Other vultures] had already arrived and were gathered in twos, and fours, and sixes at the carcasses. So many of them that it shocked me. It shocked me not that there were so many vultures together at one time but that there were dead so great in number that we might not be able to feed on all of them…That there were remains scattered farther than I wanted to see them. Thousands. Hundreds of thousands. Perhaps all the saiga in the world.

In these moments, the humans in Kolluri’s stories feel immensely far, intentionally distanced because of their complicity in the animals’ pain. As the whale in “The Open Ocean is an Endless Desert” explains, this distance was an intentional choice by humans. Humans are pushed away from the collective “we” of nature and into an othered “they”:

There is a story of a family of whales who chose to leave the sea. After they left the water, they grew legs and strayed from the shore…When they came back to the sea, they found the water had no magic for them anymore. It was unfamiliar. Our songs meant nothing to them…They didn’t belong with us.

At times, Kolluri also emphasizes this distance by cutting off communication between humans and animals. A hunter and a wolf are unable to find a common language, ultimately leading to the death of the wolf by the hunter’s gun. The glorious fabric of whale song is punctured and broken by the unintelligible sound of a ship. Kolluri’s choice of who speaks, who listens, who does not listen, and who does not understand makes us wonder: what would happen if we did listen? Would the donkey and its keeper need to grieve if their city was free of borders, free of the bombs that stripped both human and animal life from its ground? Would the polar bear instead be warmed by the bodies of other bears, “gathered in crowds on the floes. Riding them like ships…[traveling] around the whole world on the ice” if the earth were not warming? Would the bullet never have entered the head of the rhino, would the hound never have bared its teeth at the poacher’s throat, if humans did not kill for greed and pure sport?

#

In the title story, a Manticore consumes humans and nature alike, unstoppable in its hunger, reminding us that our actions have effects not only on animals, but also on ourselves. Already, people around the world treated as less-than-human (like animals, some would say) are contending with the impacts of climate change and war. The magnitude of our destruction feels impossibly large. And yet, Kolluri leaves us with a sense of hope. While we cannot undo our past, she reminds us that there can be a world in which we coexist with nature, that the path forward begins with the empathy we feel for the animals in these stories. In the closing story of this collection, an injured pigeon who can no longer fly befriends an old man known as Toy Man. To lift the pigeon’s spirits, Toy Man brings her out to the city, holds her up to the sky, and begins to run:

[A]s I gripped onto the fabric of Toy Man’s kurta on his shoulder, and he ran through the garden, I remembered something of the feeling of flying…He was not fast. Toy Man is also an old man. But I was closer to being in the sky now. I felt as though I could reach my homing lines again. They were bright and luminous and they surrounded me. These running seams that stitch the city and the world together…And this was almost like flying.

I see this stitching of the world, and I remember that nothing is inevitable. I remember that joined with nature we are a powerful force, and I begin to think that perhaps even a Manticore can be felled, if only we choose to stop feeding it.

***

Source: https://t-tees.com

Category: WHAT