(Do I really need to say spoilers? Because spoilers…)

After the cliffhanger of episode 7, I was rather relieved to get to 8. (It also didn’t make it worse that I got to see it at the London screening surrounded by other All Souls fans and some of the cast and crew. No, I wasn’t distracted by the trippiness Trystan Gravelle sitting right in front of me when Baldwin was on-screen, why do you ask?) Once again, we saw aspects of the story being adapted to screen, with a few changes and additions that fill out the story. As this is the finale, and one of the most loaded episodes, I (naturally) had a lot of thoughts. Because of this, I’ve broken this post into a series of posts; this made it easier to write and will hopefully make them easier to read!

You are viewing: What Does The Goddess Take From Diana Bishop

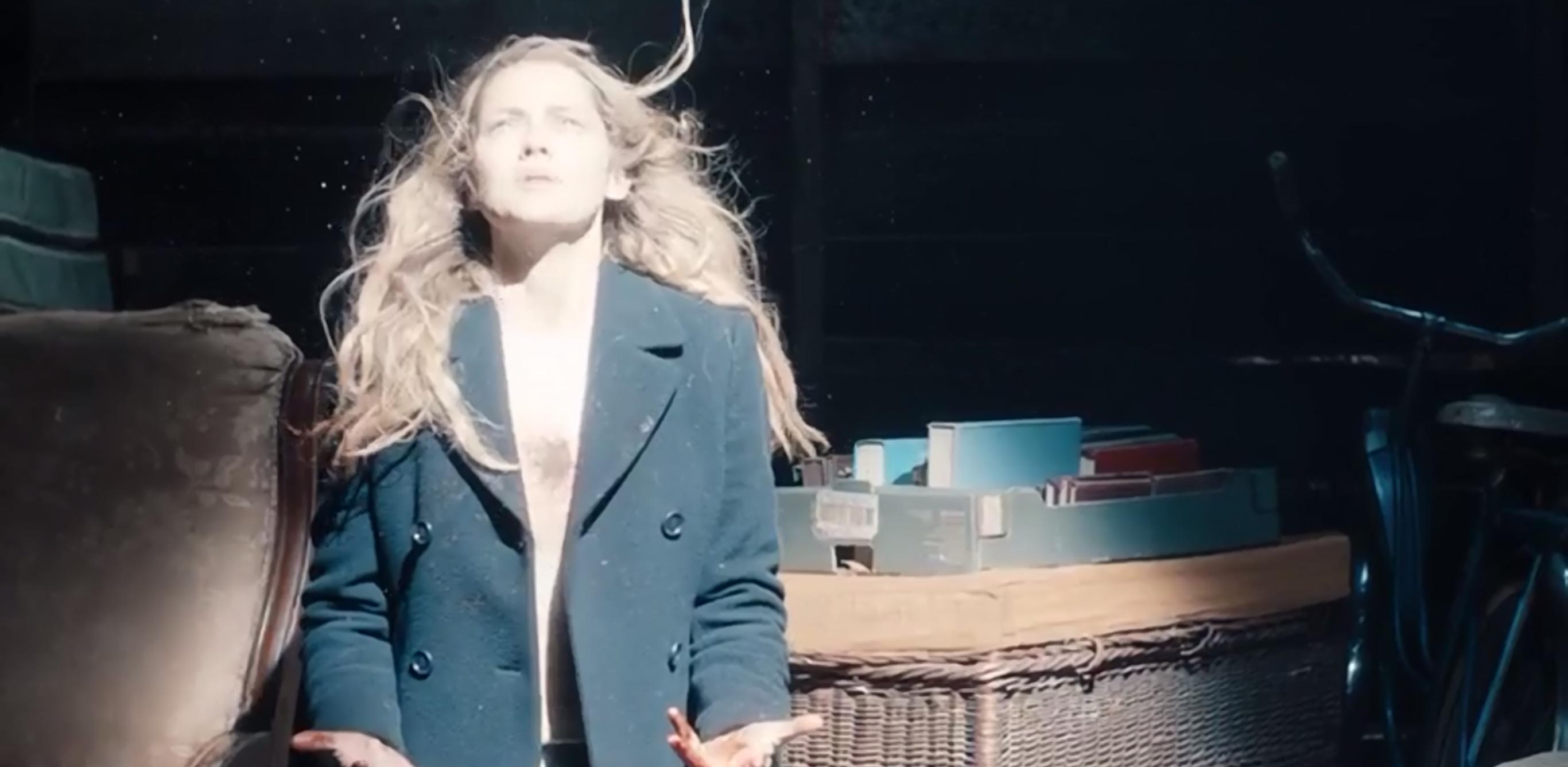

Let’s start at the beginning: I loved the way Juliette was brought into this scene. Right as we see Diana fully embracing her powers and playing a grown-up game of hide and seek that is seemingly meant to make her powers fun to learn (games, really, can be the best way of learning), we have Juliette enter and show her that she is not as powerful or in control as she might think she is. Moreover, Juliette’s presence violates the sanctity of the Bishop lands, similar to how Satu violates de Clermont sanctity to take Diana. After Juliette’s brutal attack on Matthew, we see Diana fully embrace her witch powers (and accompanying pagan beliefs) when she calls on the goddess.

I giggled a bit with at the main visual here: Diana, bathed in light and looking skyward. We do not see what she is seeing, but we can assume that she is seeing the Goddess. It comes off a bit hokey, but it also reminded me of a fictionalised, modern version of medieval spirituality. Often, Christ is compared to light, either visually or in writing.

At San Zeno, the chapel Pope Paschal built as a funerary chapel for his mother, Theodora, Christ is framed in an oculus on the roof of the chapel, as though he is looking down through it. As with other mosaics, the interplay of light creates meaning in the context of these mosaics. Here, windows throughout the chapel light the mosaics, which increases the impact of an oculus-like framing of Christ above. The gold of the mosaics is dependent on light to reveal the narrative, just as the narrative requires knowledge of Christ and Christian doctrine to reveal they layers of its meaning.* Moreover, one interpretation of the wall with the Virgin and St John (top part of the image below) interprets the light let in from the window as Christ. Light, Christ, and knowledge are conflated.

Bernini’s St Teresa in Ecstasy also came to mind as an example of the play of light in art. Bernini’s sculpture shows the saint as she receives spiritual ecstasy (and knowledge) in an encounter with an angel who pierces her heart with his spear. The sculpture is remarkable (in part) for the way light interacts with it: a window above directs the light to the saint while golden rays reflect that light and increase the drama of the scene. Her vitae also connects Christ and light as a gift, representing a type of knowledge:

For, if I say that I do not see Him with the eyes either of the body or of the soul, because it is not an imaginary vision, how can I know and affirm that He is at my side, and this with greater certainty than if I were to see Him? It is not a suitable comparison to say that it is as if a person were in the dark, so that he cannot see someone who is beside him, or as if he were blind. There is some similarity here, but not a great deal, because the person in the dark can detect the other with his remaining senses, can hear him speak or move, or can touch him. In this case there is nothing like that, nor is there felt to be any darkness — on the contrary, He presents Himself to the soul by a knowledge brighter than the sun. I do not mean that any sun is seen, or any brightness is perceived, but that there is a light which, though not seen, illumines the understanding so that the soul may have fruition of so great a blessing. It brings great blessings with it.

We also see similar ideas in the revelations of Julian of Norwich, which include a description of light that is intimately connected to Christ and the crucifix:

My sight began to fail, and it was all dark about me in the chamber, as if it had been night, save in the Image of the Cross whereon I beheld a common light; and I wist not how. All that was away from the Cross was of horror to me, as if it had been greatly occupied by the fiends. (Chapter 3)

Here, Julian describes how she loses her sight except for when glancing at the Cross, whose light does not seem to illuminate the room, but illuminates itself, drawing Julian’s attention to Christ and the crucifix as a relief from the bodily horrors and pains she goes onto recount.

Read more : What Happens If You Pull The Fire Alarm At School

The Ancrene Wisse also asks the reader be given light within, in other words, knowledge: ‘As He gave them, give you light within, to see and know him…’ Mary is also described as the Mother of Light, again revealing Christ is Light.

While a different pantheon, the connection of light to the divine is largely universal, and the scene here picks this up. While we do not see the goddess as we do in the books, we see Diana’s knowledge of her represented by the light she is bathed in when she calls upon her for aid in saving Matthew.

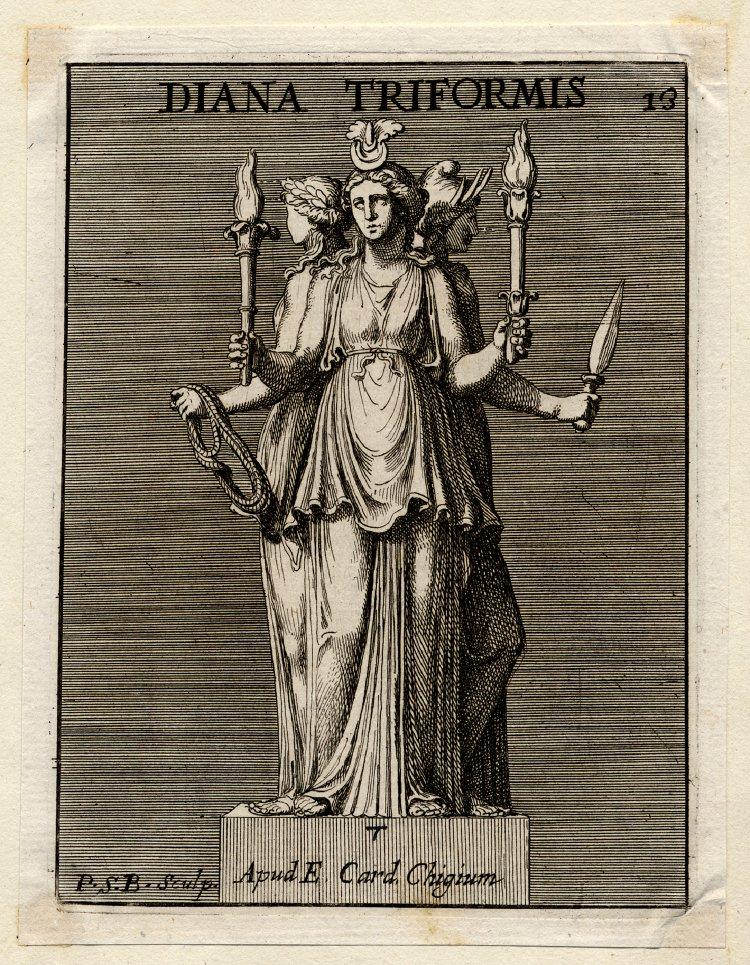

After realising Matthew is dying and her family – including Matthew – encourages her to let him go, Diana describes the goddess appearing in her three forms:

I imagined a wall of blackness and fire between me and the surprised faces of my family. The white-handled knife [which belongs to Sarah] sliced easily through the blackness and floated gently down near my bent right knee. … Two women were standing inside the barrier of flames. One was young and wore a loose tunic, with sandals on her feet and a quiver of Eros slung across her shoulders. The strap was tangled up in her hair, which was dark and thick. The other was the old lady from the keeping room, her skirt swaying. … [Diana is able to save Matthew.] I smiled in gratitude at the huntress and the ghost of the old woman, nourishing Matthew with my body. I was the mother now, the third aspect of the goddess along with the maiden and the crone. With the goddess’s help, my blood would heal him.

The book describes the goddess giving Diana the means to give Matthew her blood, as well as gives her the power of the earth to increase the potency of it, by illustrating the presence of the goddess in her multiple aspects, with Diana becoming the third (also, foreshadowing here!) as mother (the nurturer/carer). The knowledge is presented here through a bargain. The show, by comparison, gives knowledge through the manifestation of the knife Diana uses to slice her wrist open; Diana does not take it from her aunt as she does in the book: the goddess gives it to her. The light which bathes Diana in her conversation with the goddess literally manifests the knife. Light, knowledge, and agency are tied together here. It’s also manifested in blood: the light highlights Diana bleeding to save the dying Matthew. Her blood not only saves him, but conveys the story of their relationship. Blood then also becomes linked to the knowledge and light at play in the scene.

While the book describes a wall of ‘blackness and fire,’ the show illustrates a wall of light, of similar tone and quality to that which Diana was bathed in during her earlier conversation. The light acts not only as a beacon of knowledge, but visually helps set Diana and Matthew apart from the others, when the light does not reach the others who join them shortly after the attack. As in Christian theology and medieval spirituality, light becomes a type of shorthand for divinity, including its presence and divinely inspired or given knowledge.

While feeding, Matthew grabs Diana and pulls her to him, biting her neck. The neck bite we have seen with Juliette and Gerbert, Juliette and the tourist in Venice, Mathieu, Matthew and Gillian, and when Matthew bites Baldwin as he argues with his brother about rescuing Diana. In each of these instances, the bite was a way to show dominance over the person bitten, as well as get information from them in the case of Juliette and Gillian. The neck bite in this scene does not stand out in the books as unusual because we do not see it as a mark of dominance as we have seen it in the show. While Matthew bites Baldwin in their initial confrontation about Diana, the outrage of it is immediately highlighted before Ysabeau steps in and informs Baldwin he will fall in line with her rescue. This moment is brothers of largely equal standing (albeit in different ways) fighting amongst themselves whereas the Juliette and Gerbert, Matthew and Gillian, and Juliette and Matthieu scenes demonstrate a clear power imbalance.

In Shadow of Night, Matthew tells Diana that he would never take blood from her neck, telling her ‘Vampires only bite strangers and subordinates on the neck. Not lovers. Certainly not mates,’ before he explains the way vampires feed from the heart vein, noting that it is about trust and not dominance.

But the neck bite is evident in A Discovery of Witches:

‘Help me,’ I begged.

There will be a price, the young huntress said.

‘I will pay it.’

Don’t make a promise to the goddess lightly, daughter, the old woman murmured with a shake of her head. You’ll have to keep it.

‘Take anything – take anyone. But leave me him’

Read more : What Lies Beneath House

The huntress considered my offer and nodded. He is yours.

My eyes were on the two women as I raised the knife. Twisting Matthew closer to my body so that he couldn’t see, I reached across and slashed the inside of my left elbow, the sharp blade cutting easily through fabric and flesh. My blood flowed, a trickle at first, then faster. I dropped the knife and tightened my left arm until it was in front of his mouth.

‘Drink,’ I said, steadying his head. Matthew’s eyelids flickered again, and his nostrils flared. He recognised the scent of my blood. And struggled to get away. My arms were heavy and strong as oak branches, connected to the tree at my back. I drew my open, bleeding elbow a fraction closer to his mouth. ‘Drink.’

The power of the tree and the earth flowed through my veins, an unexpected offering of life to a vampire on the verge of death. I smiled in gratitude at the huntress and the ghost of the old woman, nourishing Matthew with my body. I was the mother now, the third aspect of the goddess along with the maiden and the crone. With the goddess’s help, my blood would heal him.

…

Matthew grabbed the hair at the nape of my neck. He tilted my head back and to the side, then lowered his mouth to my throat. There was no terror then, just surrender … His lips brushed my neck, sensuous and swift. I shivered, unexpectedly aroused at his touch. My skin went numb as his blood touched my flesh. He held my head firmly, his hands once again strong. … [Diana then begins to communicate with him via her blood.] I am inside you, giving you life. I repeated the mantra until it was no longer possible

So we have a contradiction within the books when Matthew bites Diana. While they are nominally married at this point (in the books, and assuming in the show though this is not addressed as such), Matthew still bites her in the neck. Partly because he is not in complete control of himself, and partly because he wants sweeter, fresher blood – needs it, arguably. Importantly, Diana notes that she surrenders in this moment to him and his needs. In the case of the Gillian, the only other witch we see bitten in this way, the terror of being bitten is palpable, and ultimately costs her her life. That which Gillian, amongst others, warned Diana would happen, does happen, but it does not cost her her life. By the very nature of the television show this moment makes us confront this bite. As readers we can skim it, focusing on other moments in the scene.

Why is this important? It heightens the tension for the viewer, for one. It also contrasts feeding and the dominance, submission of partners (mates) with that of subordinates. While it is a neck bite, which is normally about dominance, we have a change of control in the scene: Diana is arguably in the place of power initially when she offers her blood to him before he takes her neck. By the end of the scene as it is Matthew who is in control enough to stop, even if he cuts it a bit close. We have also seen Matthew struggle with Diana not following his wishes and orders; as a member of an intensely patriarchal society, Diana’s wilfulness often challenges Matthew. Whether consciously or not at this moment, a neck bite also highlights his desires to dominate her and her power, something that will be confronted time and time again in their relationship (especially in Tudor England!). There is also the fact that, ultimately, the viewer is once again forced to confront a darker, more dangerous side of Matthew and vampire life. Moreover, the carefully curated visuals to show the viewer how Matthew’s connection to Diana developed and has foreshadowed this moment. We see him go from smelling her to kissing her wrist where her blood is near the surface to his reaction when she asks him what she would taste like. The reminder that he would struggle if he fed from her as the viewer watches him feeding further highlights the danger in this scene.

That the final shot of the pair in the barn is them out of the light does not mean that Diana’s favour with the goddess has disappeared – or that her magical knowledge has diminished. The goddess has left them because her work is finished, for now. The goddess’s power is internalised by both Matthew and Diana when the goddess gives Diana the strength to heal Matthew with her blood. This internalisation will become more evident as we move to the later books and Diana accepts the goddess’s arrow as part of her body.

The other parts (these will appear as hyperlinks once I’ve finished them!):

On Congregations, Real & Shadow

On Timewalking & the Objects Necessary

*For more on the Zeno chapel, see Mackie, ‘The Zeno Chapel: A Prayer for Salvation,’ Papers of the British School at Rome, Vol. 57 (1989), pp. 172-199 and Goodson, Caroline J. The Rome of Pope Paschal I: Papal Power, Urban Renovation, Church Rebuilding and Relic Translation, 817-24. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Source: https://t-tees.com

Category: WHAT