HARLAN, Ky. — The Rev. Jim Sichko may have the best job in the world.

He was chosen by Pope Francis three years ago as a missionary of mercy and was sent out with a simple mandate.

You are viewing: Where Does Father Jim Sichko Get His Money

Do good.

On Monday, he was in Harlan to fulfill his mission.

Hundreds of miners in this rural mountain region, where coal was once king, were laid off just a few days before the Fourth of July. To make matters worse, the Blackjewel coal company deposited money in their bank accounts and then immediately clawed it back, leaving cars to be repossessed, child support to go unpaid and utilities to be shut off.

Armed with a pocket full of checks, the 52-year-old Sichko got up Monday morning to drive more than two hours from his home in Lexington to help right what he sees as a huge injustice.

“My grandfather and my uncle were miners,” he told the crowd of 70 or so people gathered in the parish hall below the Holy Trinity Catholic Church. “I feel a connection to you.”

A long line snaked out the back door and continued to grow over the next hours.

To see Sichko in action, you’d swear he’s part Roman Catholic priest and part game show host.

Opinion:Mitch McConnell is silent on coal while Kentucky miners suffer and die

Monty Hall. With a Roman collar and a crucifix.

He said he refined his style by watching talk show host Ellen DeGeneres.

“Who was the first person in line this morning?” he bellowed, before whipping out a couple of crisp $100 bills for the two miners who agreed they arrived at the church at the same time. “Who’s the oldest miner here?”

Read more : Where Is Rannis Rise

Another $100 bill.

“Who’s the youngest?

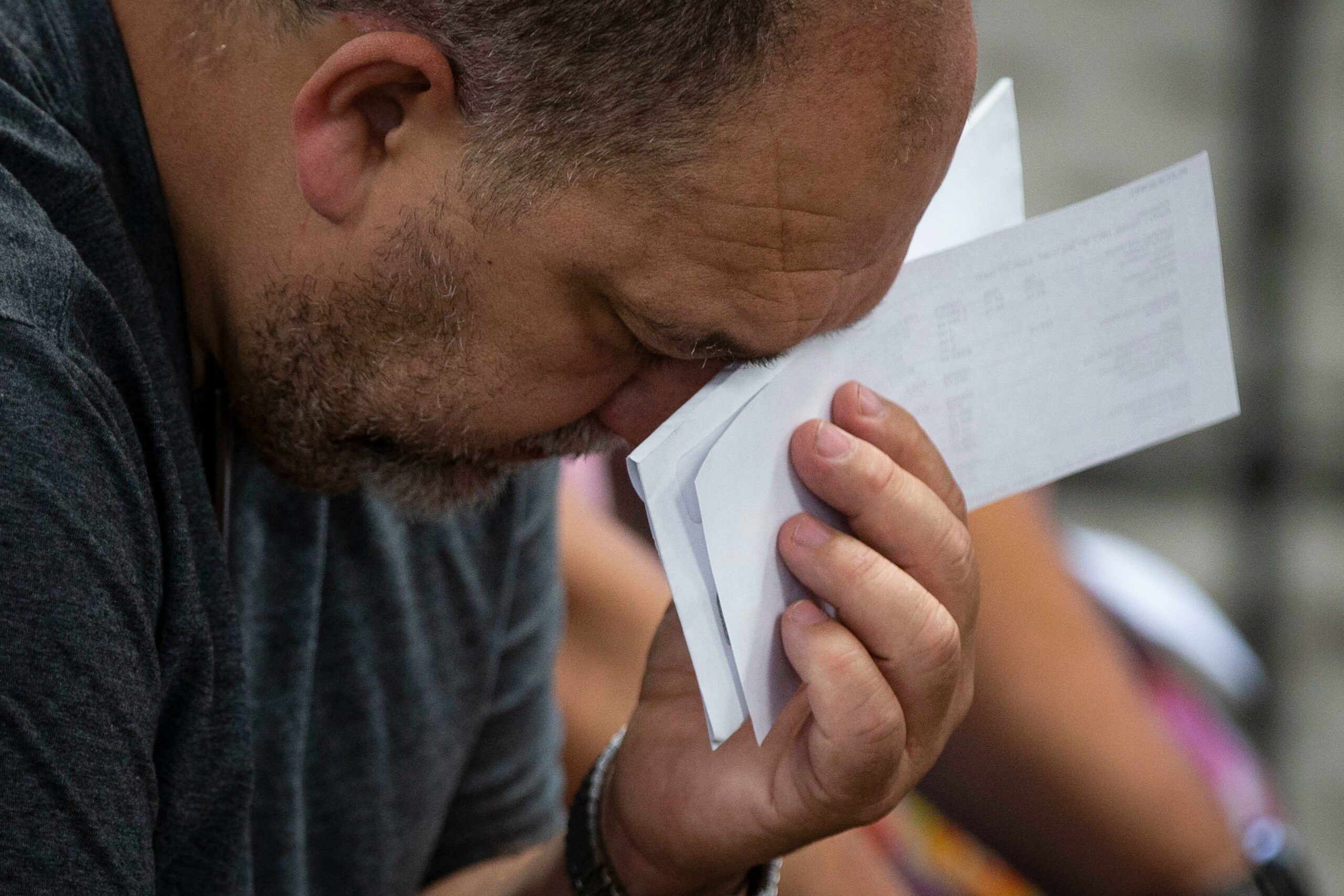

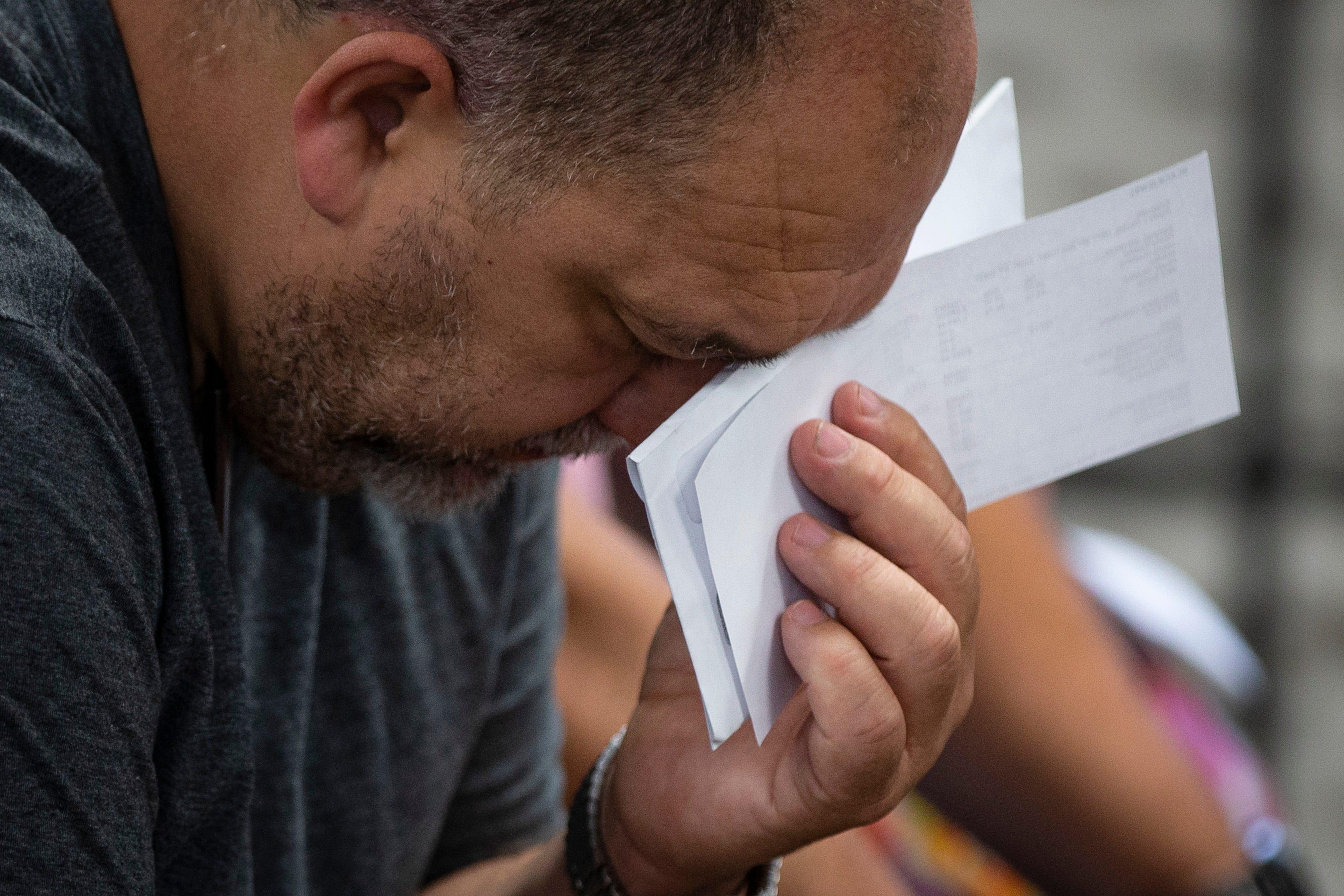

Jeff Middleton, who worked at a Blackjewel mine in Leslie County before he was laid off, misted up after Sichko wrote a check to pay his power bill and gave him $100 cash for being first in line. He and his wife, Amanda, almost didn’t come when they heard a priest from Lexington was coming to give away money.

“We thought it was too good to be true,” said Middleton, who has been laid off from mines five times over the past few decades as the coal companies have continued to retrench after the industry reached its peak here about four decades ago.

He’s not sure what he will do now.

He was retrained to be a lineman on utility crews and also learned to be a phlebotomist, but he said those jobs aren’t any easier to find than mining jobs.

“I can’t get a job at neither one,” said the father of three. “I don’t know what we’re going to do.”

Sichko said he came to be in Lexington about 20 years ago after he was sent to Orange, Texas, and was rejected by the Catholic diocese there because the bishop didn’t think he had what it took to be a priest. He instead came to Kentucky to work with the poor in Appalachia.

See also:Motel’s closure leaves residents facing a housing crisis

Why Francis named him as one of about 1,000 missionaries of mercy worldwide is anyone’s guess, he said.

The pope has given them permission to hear confessions in any diocese and the authority to forgive certain sins that might otherwise require the pope’s approval.

The missionaries have spent the last three years traveling the world doing good deeds. Some of the priests have focused on granting forgiveness and giving uplifting speeches. Sichko, who is originally from Pittsburgh, has spent the last three years traveling the country committing random acts of kindness.

In Texas, he put out on social media that he would buy dinner for anyone who came to a barbecue restaurant one day. In California, he stood at an In-N-Out Burger drive-thru window and paid for everyone’s meals.

At a Starbucks one Christmas, when baristas’ tips plummeted after some complained the chain’s cups weren’t Christmass-y enough, he went and tipped all the employees $100 each. In Corbin, Kentucky, he gave 100 second graders brand new bicycles.

He’s got a simple message for those he helps — “Pay it forward.”

Read more : Where Does Bobby Parrish Live

One miner, worried Sichko’s funds would run out before he got to everyone, took that to heart. He offered to move to the back of the line because others needed the help more. “Some of these people have more kids than I do,” said Andrew Burton, a 33-year-old miner who worked at Blackjewel’s Cloverlick mine in Cumberland.

“Some of them are in worse shape than I am,” he said. “You’ve got to be a light to people.”

“Sit down,” Sichko said as he continued to verify Burton’s paperwork despite Burton’s protests. “Sit down.”

He paid his bill.

For more than two hours at Holy Trinity, Sichko sat at a table and spoke to miners and their families as he wrote checks.

More from Appalachia:Courier Journal editor explores Eastern Kentucky

Father Jim Sichko (@JimSichko) | Twitter

He cracked jokes, asked one man how much he’d take to shave off his long red beard, and urged one miner to go to his car to get his miner’s helmet. “I’ve got to try this on,” he said, before slipping it on his head and taking a selfie.

“They don’t get me,” he said each time one of his quips seemed to fall flat.

Sichko said he hadn’t even heard about what had happened at Blackjewel until a parishioner at Holy Trinity contacted him on social media last week. He threw together Monday’s event with the help of church members and Catholic Charities.

“I go and do things that speak to my heart,” he said. “This speaks to my heart.”

Sichko had budgeted $15,000 for the miners and brought with him 44 checks. By the time he left Harlan, he had gone through all 44 checks and then began just accepting people’s utility bills and promising to have the bank cut checks for all of them.

In all, he helped pay bills for 119 miners — totaling $20,434.55 — including paying an entire year’s worth of electric bills for Richard Barnard, the last miner in line.

“The last always is first,” Sichko said, paraphrasing the Book of Matthew.

Joseph Gerth’s opinion column runs on most Sundays and at various times throughout the week. He can be reached at 502-582-4702 or by email at [email protected]. Support strong local journalism by subscribing today: courier-journal.com/josephg.

Source: https://t-tees.com

Category: WHERE