“At every important moment of Daisy’s life, she’s alone. No one to turn to, no one she can really trust.” — Natalie Wood, quoted by Gavin Lambert in Natalie Wood: A Life (2004).

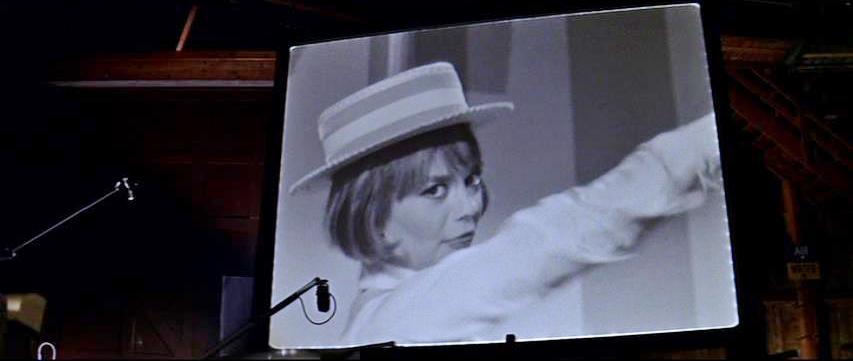

“Daisy Clover? That’s your real name?” “Yeah . . . it’s the one thing about me they haven’t changed.” Daisy (Natalie Wood) awaits a reaction from the studio crew and executives after she sings for her first screen test. It is also the first time she has sung to an audience of any kind. She is met with stony silence. Inside Daisy Clover (Warner Brothers, 1965, dir. Robert Mulligan).

You are viewing: Who Sang For Natalie Wood In Inside Daisy Clover

***

Movies about the movies have been with us almost as long as motion photography itself. Tales of the trials and tribulations of movie stardom — the attaining and the maintaining of it — date to the birth of the concept of “movie star,” circa 1910. “Inside” stories of the machinations of the film industry began with its emergence from a cottage industry in the years during and after the first world war. Proliferating in the 1920s, by the 1930s these stories became film cliché. Not until the 1950s did we see a trend toward a new, post-war realism in which movies about the movie-makers reflected the cold cynicism of film noir — The Bad and The Beautiful, In a Lonely Place, and Sunset Boulevard, films that examine the powerful, the peripheral and the pathetic of the industry known as “Hollywood.”

I can think of no prior film as relentless and unflinching in its depiction of the American film industry as a bottomless pit into which the dreams and aspirations of its would-be inhabitants are dumped as Inside Daisy Clover (Warner Brothers, 1965), directed by Robert Mulligan, adapted by Gavin Lambert from his 1963 novel.

Natalie Wood is Daisy Clover, a talented but coarse teenager who gets a one-in-a-million chance at stardom when a cheap acetate vocal recording gets her an audition at a major Hollywood studio. Although at first glance it appears a classic tale of “be careful what you wish for,” Daisy’s self-described “simple healthy instincts” protect her against the total, soul-crushing annihilation that might have befallen a weaker person dreaming of movie stardom. Nevertheless, the non-stop emotional and psychological battering she receives during her relatively brief journey through the land of make-believe is staggering.

Natalie Wood is Daisy Clover, a talented but coarse teenager who gets a one-in-a-million chance at stardom when a cheap acetate vocal recording gets her an audition at a major Hollywood studio. Although at first glance it appears a classic tale of “be careful what you wish for,” Daisy’s self-described “simple healthy instincts” protect her against the total, soul-crushing annihilation that might have befallen a weaker person dreaming of movie stardom. Nevertheless, the non-stop emotional and psychological battering she receives during her relatively brief journey through the land of make-believe is staggering.

At the end of 1964, Natalie Wood found herself at a career crossroads. A strange circumstance for someone who had recently made four consecutive critical and popular hit films — West Side Story, Splendor in the Grass, Gypsy and Love with the Proper Stranger — two of which earned her Academy Award nominations for Best Actress. Strange indeed for the second highest-paid actress in motion pictures — she trailed only Elizabeth Taylor in earning power, roughly $1M per picture for Taylor compared to Wood’s $750k. In terms of demand for her services at the time she was arguably Taylor’s equal.

Natalie Wood’s contract with Warner Brothers allowed her one “outside” film project per year, and she had recently used up that option with her Oscar nominated performance in Love with the Proper Stranger (1963) for Paramount. In early 1964, Warner Brothers dictated that her next two “home studio” projects would be comedies, bland but safe films opposite veteran, bankable stars: Tony Curtis, Jack Lemmon, Henry Fonda and Lauren Bacall. Sex and the Single Girl and The Great Race did mediocre box-office (and “Race” was one of the most expensive comedies made to date). Both films were hammered by critics. They were, simply put, awful. While they did no immediate harm to her career, they did nothing to advance Wood’s reputation within the film industry as an actress of genuine ability.

Natalie Wood had balked at The Great Race, but Warner Brothers refused to release her for another outside project unless she accepted the assignment. Complicating matters, the two comedies combined had taken most of 1964 to complete. Sex and the Single Girl was shot in California in a little over two months in the spring. But The Great Race went months over schedule. Shooting commenced in May on location in Austria and, after returning to the studio in September to complete interiors and dialogue dubbing, work on the film continued well into December. The delay cost Wood the opportunity to accept another project, The Collector, with director William Wyler who had asked her to play opposite Terrence Stamp in the film, one which was far more prestigious than either of the projects forced upon her by Warner Brothers.

Fortunately, while searching for other outside film projects, Wood learned that the producer/director team of Alan Pakula and Robert Mulligan, with whom she had made Love with the Proper Stranger, were looking to film an adaptation of Inside Daisy Clover, a novel that Wood had read and loved. She knew the author, Gavin Lambert, though not well. She called him and said she would “kill for the part.” Lambert told her not to worry: she was exactly the actress they had in mind for Daisy.

After a tentative agreement to distribute the film through Columbia Pictures fell through, Pakula and Mulligan’s production company, Park Place Productions, enlisted the services of Warner Brothers. Though most of the film was shot on the WB lot, which served as “The Swan Studio” in the film, Natalie Wood’s contract for Inside Daisy Clover was with Park Place, from whom she would receive $750k against ten percent of the gross receipts. (Ironically, though released through Warner Brothers, Inside Daisy Clover would be considered an “outside” project under her Warner’s contract.)

Production began in mid-February, 1965, with rehearsals for the principal players: Christopher Plummer, Ruth Gordon, Katharine Bard, Roddey McDowall, Robert Redford and Wood.

Christopher Plummer, as the iron-fisted studio head, Raymond Swan, had most recently played Captain Von Trapp opposite Julie Andrews in The Sound of Music, released just as production of Inside Daisy Clover began. Before the latter was completed, he would be a star much in demand, and another box-office draw for the film along with Natalie Wood. For Robert Redford, however, it was his first major film and his first important role.

Though Redford had appeared in a couple of minor films, he was best known for his recent work on Broadway, where he played leading roles in two hit productions, Sunday in New York (1961-62), where Natalie Wood had first met him backstage, and Barefoot in the Park (1963-64). She thought he was ideal for the part of Wade Lewis, the suave bisexual/homosexual (depending upon the draft of the screenplay or edit of the film) superstar of The Swan Studio. Redford has always credited Natalie Wood for his being brought into the project in a role that essentially kick started his film career.

Wade Lewis was not merely breakthrough role for Redford — the character was a landmark for Hollywood. Although the prospect of making a film where a pivotal character is homosexual likely caused other studios to shy away from the project (and possibly nixed the original distribution deal with Columbia), it marked the first time in a mainstream Hollywood film that a gay or bisexual character is allowed to function as a normal person without having to be suicidal, depressive, homicidal or otherwise facing punishment by society merely for being who they are. Wade Lewis may be a rotten bastard, but not because of his sexual orientation.

Katharine Bard, whose career was primarily in television (in more than 50 series, anthologies and made-for-television features in the 1950s and 60s), played Melora Swan with an icy sweetness that makes her later explosive scene with Daisy all the more unexpected and intense. Roddey McDowall, already a close friend of Natalie Wood and a fellow child actor, had a small but noteworthy role as Baines, the efficient assistant to Swan, who allows just a hint of his pleasure at Daisy’s misfortunes to become evident with his sparse, but pithy and ironic commentary (Miss Clover, you’ll find your shoes on my desk. . . Is there anything you need, Mrs. Lewis?”). Wood also developed a lasting friendship with Ruth Gordon, a successful stage actress, author and screenwriter (Adam’s Rib, Pat and Mike, The Actress), whose film acting career was revived by Inside Daisy Clover, with notable successes (Rosemary’s Baby, Harold and Maude) in the years that followed.

Natalie Wood saw the project as an important step, not only as an actor, but as a filmmaker. At this point in her career, she was able to command important concessions on movies made outside her home studio. She had approval of director, co-star, and cinematographer, in addition to the traditional perks of a star actress over matters such as costume designs, makeup artists and hair dressers.

Wood had already earned a reputation for business acumen unusual for a star of the period. A Life Magazine profile in December, 1963, spoofed this with a photo of Wood meeting with her business managers, agents, lawyers and accountants as if she were chairing a board meeting of a fictional Natalie Wood, Inc. She had expressed to her closest friends a strong desire to “do things on my own.” As Gavin Lambert would later write in his biography of the actress, “1965 was as close as she would ever get to realizing [that] ambition.”

In Lambert’s novel, it is 1951: we are introduced to Daisy Clover, age thirteen, going on fourteen, living in Playa del Rey, a faded seaside community with her equally faded mother, The Dealer, who spends her days playing solitaire. Her father abandoned his family years earlier.  Daisy keeps her vocal talent to herself, making cheap acetate records of her voice, a capella, in a recording booth at the Venice pier — a kind of instant record that sailors about to embark on a long voyage could make and send to their loved ones.

Daisy keeps her vocal talent to herself, making cheap acetate records of her voice, a capella, in a recording booth at the Venice pier — a kind of instant record that sailors about to embark on a long voyage could make and send to their loved ones.

In Lambert’s screen adaptation, it is 1936 and Daisy is fifteen, living in a trailer along the boardwalk in “Angel Beach” (shot in Santa Monica) selling celebrity photos with fake autographs. We watch Daisy forge a “Myrna Loy” that causes a satisfied customer to squeal with joy: “Our handwriting looks the same!”  The Dealer (Ruth Gordon), who Daisy affectionately calls “old chap,” spends her days playing solitaire and consulting a card reader to see what the future holds. The biggest obstacle to stardom for Daisy is her mother, who is teetering on the edge of reality, slipping into dementia, despite constant pleas from Daisy to “concentrate, old chap!” (In Lambert’s novel, Daisy’s biggest obstacle is Daisy herself. She is what was once referred to as a “non-conformist.” Her intelligence, wry sense of humor and independence, combined with her inexperience and immaturity, give her a comically self-destructive streak. Her early success and stardom only give her more leverage to act in opposition to all authority figures.)

The Dealer (Ruth Gordon), who Daisy affectionately calls “old chap,” spends her days playing solitaire and consulting a card reader to see what the future holds. The biggest obstacle to stardom for Daisy is her mother, who is teetering on the edge of reality, slipping into dementia, despite constant pleas from Daisy to “concentrate, old chap!” (In Lambert’s novel, Daisy’s biggest obstacle is Daisy herself. She is what was once referred to as a “non-conformist.” Her intelligence, wry sense of humor and independence, combined with her inexperience and immaturity, give her a comically self-destructive streak. Her early success and stardom only give her more leverage to act in opposition to all authority figures.)

But in both the novel and the screen adaptation, there is no lengthy struggle up the ladder of success to fame and stardom. Daisy’s recording, sent to a motion picture studio, is the winning entry in a studio-sponsored talent contest. She has won an interview, an audition and a screen test, without so much as a photograph.

But in both the novel and the screen adaptation, there is no lengthy struggle up the ladder of success to fame and stardom. Daisy’s recording, sent to a motion picture studio, is the winning entry in a studio-sponsored talent contest. She has won an interview, an audition and a screen test, without so much as a photograph.

A limousine is sent to meet her, sweeping her up and away to The Swan Studio (actually the Warner Brothers studio in Burbank), with its iron gate closing behind. She is escorted through the lot, dwarfed by the imposing, canyon-like walls of the stages. Daisy may have loomed large in her seaside existence compared to her surroundings, but in this strange world where fantasy is carefully manufactured, she is made tiny, physically and psychologically insignificant. This motif — Daisy vs. Goliath, if you will — dominates the film during the several sequences after we are introduced to our Raggedy-Ann heroine. Huge sound stages, vast offices and endless corridors provide a physical contrast to the diminutive Daisy. (That is, until she gets over her awe at her new environs and reasserts her native abrasiveness when the star-making machine begins to form her into something she is not.)

“I should explain that I’ve never been movie-struck. I always go to Cary Grant pictures and I admire Myrna Loy for her poise, but the idea of getting in the movies and hobnobbing with all that crowd never meant much. I want to sing, but that’s different.” [From the novel, Inside Daisy Clover, by Gavin Lambert (The Viking Press, 1963).]

“We’d reached the entrance to some large, ordinary dump. I looked around and saw high wire fences and rows of gray buildings without windows. . . it felt for a moment like we were waiting outside a jail.” [From the novel.]

Daisy enters the cold, dark cavernous interior of a sound stage, where she meets Raymond Swan (Christopher Plummer) and his wife, Melora (Katharine Bard), and is given a camera test.

Daisy enters the cold, dark cavernous interior of a sound stage, where she meets Raymond Swan (Christopher Plummer) and his wife, Melora (Katharine Bard), and is given a camera test.

“Right where I’m standing now it’s very bright-but beyond all this light everything looks very dark. Somewhere, people I can’t see are hammering. Anybody I can see is a shadow. Way up above on a platform, there’s an old man grinning and pointing a spotlight at me.” [From the novel.]

Daisy sings in public for the first time.

“Then they’re yelling, ‘Quiet please!” etc., and Mr. Swan says in his quietest, coldest, farthest-away voice, ‘Daisy,’ the piano player rattles out a few chords, and we’re off to the races. As far as I’m concerned, this whole enormous barn shrivels right up and I’m back in that booth and can just hear the sound of the ocean. And it all seems to be over before it started . . .” [from the novel].

“Then they’re yelling, ‘Quiet please!” etc., and Mr. Swan says in his quietest, coldest, farthest-away voice, ‘Daisy,’ the piano player rattles out a few chords, and we’re off to the races. As far as I’m concerned, this whole enormous barn shrivels right up and I’m back in that booth and can just hear the sound of the ocean. And it all seems to be over before it started . . .” [from the novel].

Although unsure of what kind of reaction to expect, she is dumbfounded by the reaction she sees: nothing — she barely exists to the studio crew.

In the dark behind the lights Swan, his wife and assistant quietly confer.

In the dark behind the lights Swan, his wife and assistant quietly confer.

“Melora comes over and kisses me-lightly, though, on the forehead-and Mr. Swan says, ‘You did pretty well, Daisy, considering everything,’ which I guess is a big hand from him. . . . They turn off the lights and someone slides back the wide door at the other end of the barn.” [From the novel.]

“Melora comes over and kisses me-lightly, though, on the forehead-and Mr. Swan says, ‘You did pretty well, Daisy, considering everything,’ which I guess is a big hand from him. . . . They turn off the lights and someone slides back the wide door at the other end of the barn.” [From the novel.]

“Mr. Swan had said, ‘We’ll call you tomorrow, Daisy.’ Now I still don’t care about being in the movies, of course, and-wait a moment, what the hell, scratch, that’s the most solid lie I ever told. Like a sail needs wind I want to get in the movies!

. . . The phone rang at ten o’clock the next morning.” [From the novel.]

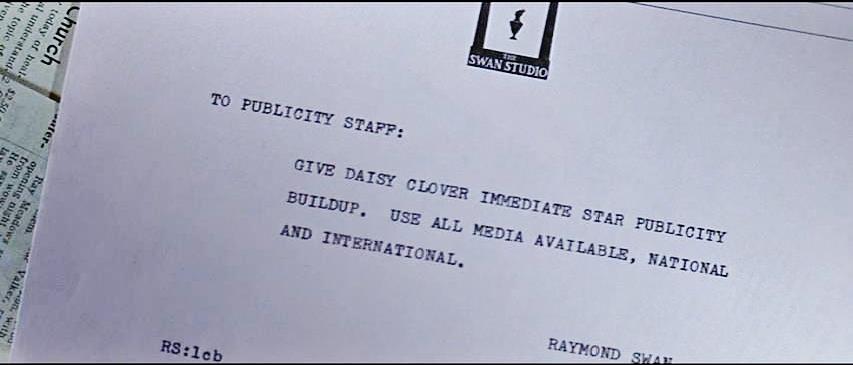

Raymond Swan appears in person with the news: Daisy will be Swan Studio’s newest star.

“Incredible as it may seem, I’m gonna make something out of you.” “What?” “Money — there’s a certain mixture of orphan and clown that always packs them in. It has a dirty face, a heart of gold . . . and it sings. It doesn’t smoke, or bite its fingernails or cut its hair without permission. It becomes ‘America’s Little Valentine.’”

Daisy will soon learn that he has already begun to make arrangements for Daisy’s older, married sister, Gloria, to become Daisy’s legal guardian, her legal representative. Swan sees immediately that Daisy’s mother is a problem that must be resolved before he can begin to create his new star.

Daisy’s mother, living on the far edge of reality, has retreated into their trailer which is soon billowing with smoke.

Daisy’s mother, living on the far edge of reality, has retreated into their trailer which is soon billowing with smoke.

“It’s getting pretty hot in there!”

Daisy is left alone outside Swan’s office while Swan, her sister and sister’s husband finalize Daisy’s contract, living arrangements and the problem of The Dealer. She must wait for Baines (Roddy McDowall), Swan’s assistant, to buzz her into the office.

“They’re ready for you now, Miss Clover.”

The offices of The Swan Studios are cathedral-like spaces, but hollow and absent of faith in anything other than commerce. (In the novel, the Swans’ mansion is a former Spanish Catholic mission, with a nunnery converted into bedrooms and a wet bar).

Daisy is a minor. Swan and Sister Gloria (Betty Harford), as Daisy’s legal guardian, agree upon her new contract, and they have Mrs. Clover declared mentally incompetent to care for Daisy, or herself.

Daisy will live with Gloria and her husband; her mother is committed. Melora: “You’re going to be very famous very soon. People will want to know everything about you. They’ll shine bright lights into all your dark corners. Now think of the pain if they tell about your mother. They will, unless we protect her.” Swan: “Unless she’s officially dead.”

Swan and Melora assure Daisy that stardom will be well worth the present unpleasantness. Why, in a couple of years she’ll be free to do as she wishes — and she’ll have plenty of money with which to do it!

The Dealer is taken to the “Twilight Convalarium.”

Daisy is resilient, a tough and prickly ragamuffin. She is given an exterior makeover, something she seems just able to tolerate in return for her chance at stardom. But it is the remake of her person that galls her: “America’s Little Valentine.” She rehearses with Swan the responses to questions she’ll receive at her introduction to the Hollywood press, her “coming-out party” during Christmastime at the Swan estate.

Swan: Alright, Daisy, once more straight through: We hear the picture’s a smash, you were sensational . . . Daisy: It’s the most exciting moment of my life. Swan: Who are your favorite motion picture stars? Daisy: Fred Astaire and Myrna Loy. Swan: Stand up, stand up! Tell me why. Daisy: They have elegance and poise. I wish they’d been my parents. Swan: Who were your parents? Daisy: My father died in a train crash when I was nine. Swan: And what about your mother? Daisy: (hesitates) Swan: Well what about your mother? Come on, come on! Daisy: (softly) She died . . . last year. Swan: I didn’t hear you. Daisy: My mother died, too, last year.

Swan: Oh I’m so sorry. What was she like? What do you remember most about your mother? Daisy: (hesitates again) Swan: Oh, come on, Daisy, come on! You’re mother loved music, her . . . last . . . wish . . . was . . . Daisy (with Swan simultaneously): . . . to hear me sing once more. Swan: Fine! (to his assistant Baines) Kill the choir, dim the lights in one minute.

Melora: Now ‘come let them adore you,’ dear.

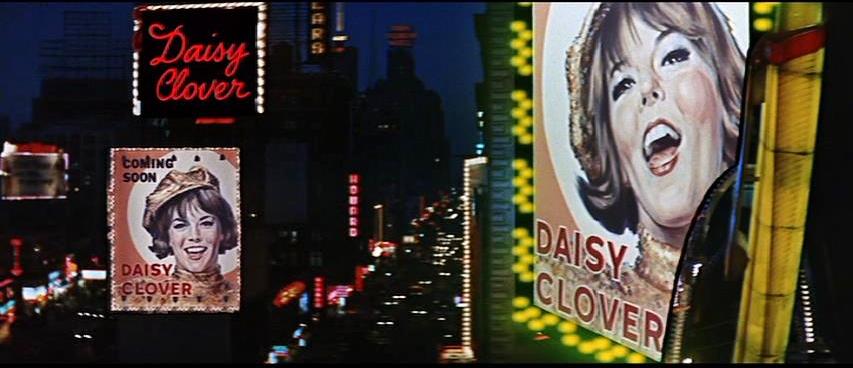

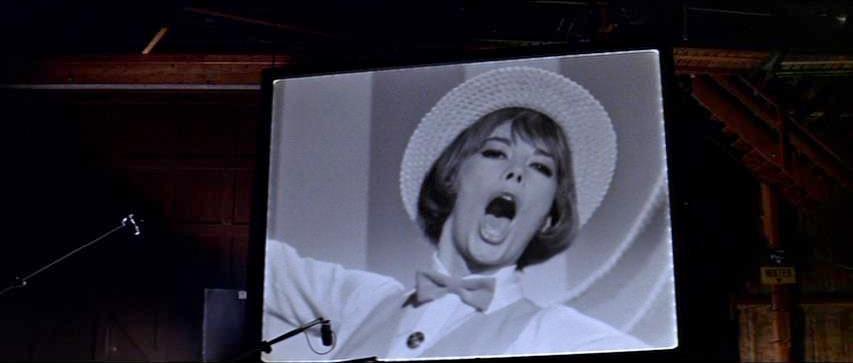

Daisy’s coming-out, her introduction to the press, is a publicity film with an elaborate production number, “You’re Gonna Hear From Me,” to promote The Swan Studio’s latest star, the singing sensation, Daisy Clover.

“You’re Gonna Hear From Me” includes staging that borrows liberally from Busby Berkeley’s dance direction in 1930s Warner Brothers musicals, particularly Footlight Parade, with its image of Ruby Keeler formed by flags wielded by the dancers.

“The world has met Daisy Clover. Now — Daisy Clover meets the world!”

Before she is to appear as part of the Christmas Choir providing the live entertainment for the event, Daisy is given a few minutes alone in Melora’s bedroom to relax after her public début. There she meets the studio’s reigning male heart-throb, Wade Lewis (Robert Redford).

“Daisy Clover? That’s your real name?” “Yeah.” “Sure?” “Yeah. It’s the one thing about me they haven’t changed.”

“It’s the one thing about me they have.” “Your real name isn’t Wade Lewis?” “No. No, it isn’t. It’s Lewis Wade. They took a poll and decided it was sexier the other way around.”

Wade convinces Daisy (without having to make much effort) to blow off the choir, raid Melora’s liquor cabinet and go for a ride in his yellow Rolls. It is Daisy’s first act of rebellion. Melora, who arrives before they take off, knows precisely what Wade is up to with the impressionable Daisy.

Melora: “She’s scheduled to sing with the choir!” Wade: “Well, have a ‘black mass’ instead!”

Melora: “She’s scheduled to sing with the choir!” Wade: “Well, have a ‘black mass’ instead!”

Wade later surprises Daisy as she visits her mother at the “Convalarium.” The Dealer has stopped speaking. (In the novel, this is the result of electro-shock treatments; the film leaves her silence unexplained.)

On the night of the big première of her first movie, Swan has learned that Daisy and Wade have been visiting the “deceased” Mrs. Clover.

Swan: “There are certain risks which must never be taken. From now on I can’t allow you to see her any more.”

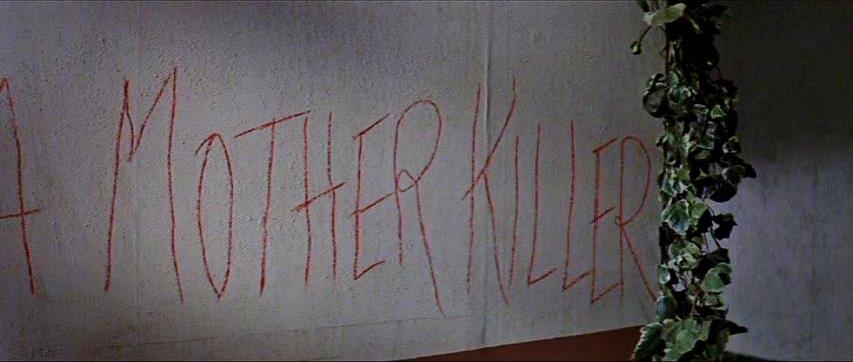

And Daisy finally explodes in rage.

Wade: “I agree!”

Daisy blows off her première to escape with Wade Lewis.

On Wade’s yacht, the couple hides out, spending the night together.

By morning, Wade has disappeared.

Wade’s note to Daisy is cryptic — and he has signed it with his real name, Lewis Wade. (The note is reminiscent of the one left to Jean Harlow by her new husband, Paul Bern, when he committed suicide after their wedding night. Some thought it an indication that he was homosexual, and unable to perform sexually with her. The note likewise impugns a similar motive to Wade, minus the suicide of course.)

But Swan’s eyes, in the person of Baines, miss nothing.

Called into Swan’s office, Daisy expects the worst. Swan, however, has good news.

A new contract. “The future. It’s worth a lot more money. Well, don’t thank me. The picture was a triumph — you’re going to the top of the tree. In the meantime, fame does have its obligations. . . .

. . . We wouldn’t want the newspapers telling us how America’s Little Valentine ‘lost her shoes.’”

Baines: “Miss Clover, you’ll find your shoes on my desk.”

Wade reappears weeks later, with an apology and postcards he never sent. [See this sequence in detail in this prior post.]

Daisy accepts Wade’s sudden proposal of marriage, in defiance of Swan.

Swan: “And it hasn’t even had its first screen kiss!”

After a long drive out into the desert on their wedding night, Wade disappears by morning.

Innkeeper: Could I have your autograph?” Daisy signs it by rote, as if she were still forging the signatures of stars on photos at Angel Beach.

“You’re not Myrna Loy!“

Daisy is once again totally alone, dwarfed by place and circumstance.

“Mr. Swan is meeting with your lawyer. He’ll see you in the morning. Is there anything you need, Mrs. Lewis?”

Melora: “I cut myself when Wade left me . . . Would you like to cut yourself? Would you like to get drunk? I know! You need a good laugh!”

A drunken Melora calls Wade in New York — but another male answers.

Melora to Daisy: “That’s the new lover. I didn’t get his name but he sounds charming. Your husband never could resist a charming boy!”

[It was the insertion of this line, over-dubbed by Katharine Bard while Melora has her face away from the camera, that upset Robert Redford. According to both Redford and Gavin Lambert, the character of Wade Lewis was originally written as a homosexual, but Redford agreed to play the character on the condition that Wade be changed to bisexual, a role he felt he could play much more convincingly, and Lambert agreed to the change. Prior to the film’s première, the change back to homosexual was made by inserting Melora’s new line about the “charming boy” because the producer, director, and writer Lambert all felt that the motivation behind Wade’s behavior toward Daisy was confusing to the audience, and that making him plainly homosexual made for a clearer plot line. Redford was furious — he found out about the change after the film premiered! But as he told Natalie Wood biographer Suzanne Finstad, “Because I liked them [Pakula and Mulligan] and I was pretty young, I chose not to make a big deal out of it. I just went on with my life.” (Finstad, Natasha: the biography of Natalie Wood; Harmony Books, 2001).]

Swan takes Daisy into his own hands . . .

And into his arms. He arranges for Daisy and her mother to live together in a house on the beach; for a time The Dealer and Daisy are together and at peace.

The beach house shared by Daisy and The Dealer. [Originally belonging to actress Barbara LaMarr, this house had been condemned and scheduled for demolition when it was purchased for the film and moved to the seaside location.]

Daisy: “It’s alright! No one’s ever gonna come for you again. It’s all right.”

But work must continue on the next film.

“When the circus came to my home town,

it was fine and funny and shiny new.

So when it left from my home town,

well, of course, I left with it too.

Wouldn’t you?”

The second and last survivor of the original three production numbers written for Inside Daisy Clover by André and Dory Previn, The Circus is a Wacky World, is a hall of mirrors. Daisy’s number in her latest film is intended to spoof the make-believe, cardboard and canvas world of the circus, while at the same time the “Swan studios film crew” shoots her in various camera set-ups, and all the while the crew of Inside Daisy Clover follows every move of Daisy and her crew so that we may see every layer of the fiction.

After an exhausting shoot, Baines informs Daisy that she has a meeting with Mr. Swan in the morning. Baines drives her back to the beach house. When Daisy gets home, she finds a stranger than usual silence . . .

“To my surprise, she was sitting up in bed and watching the early-morning program, somebody lecturing of Faith. The room was extremely untidy, the wind had blown every window open during the night and scattered all her cards, they lay across the floor and the bed. There was even a jack of diamonds stuck in her hair. She didn’t look at me, and a moment later I realized she wasn’t looking at the TV either. I didn’t even have to touch her cold hand to know she’d played her final solitaire.” [From the novel-set in the 1950s, which explains “the TV.”]

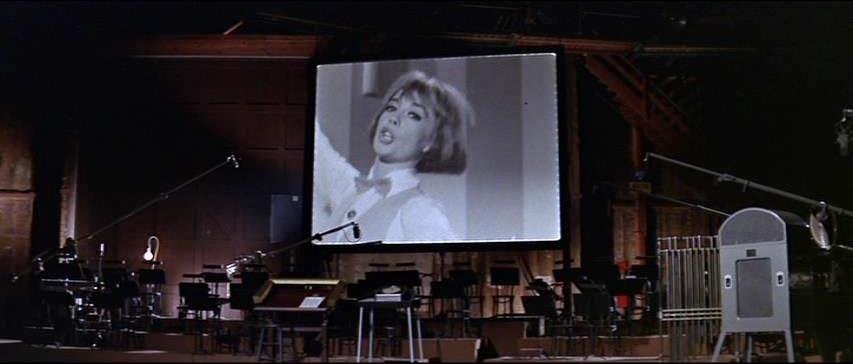

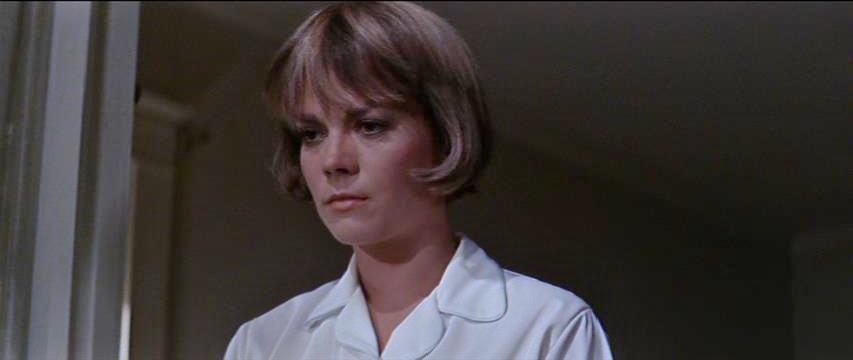

Daisy returns to the studio to complete the dubbing of the “Circus” musical number. The first shot, below, is reminiscent of Daisy’s entrance into The Swan Studio for her first screen test, and brings us full circle from her initial steps toward movie stardom.

The dubbing booth is eerily similar to the recording booth on the pier at Angel Beach, where her story began.

All of the strain, accumulating ceaselessly, finally causes her to crack wide open . . .

Daisy is mocked by her own image on the screen.

Daisy is mocked by her own image on the screen.

* * *

Swan: “Now look here, if she’s sane, cure her. Is she’s mad, certify her. I want her cured so I can finish my picture or certified so I can collect the insurance.” Doctor: “Miss Clover is not certifiable.” Swan: Then she’s sane, and she’d better get up.”

“Trust me Daisy. If there’s a problem, I can solve it. I always have.”

“The world is holding its breath because my little ‘street Arab’ is holding hers. That’s something. The world identifies with you. Bonehead.”

Melora: “I only hope he’s what you need. Ray, I mean. Now. Why don’t you get up and finish the picture and take a long exciting trip. We could go around the world together if you’d like. Try and hang on anyway. Like me.”

“Dear Heart. Yellow Roses, sweet sherry. You can’t stop singing. The world’s still a garbage dump. I don’t blame you for holding out, of course. The hounds are still after you.”

“Won’t you join me back in the limelight, ‘little Lady of Pain?‘”

“Mayn’t I pronounce you officially alive!”

Swan returns, determined to break Daisy. He dismisses her nurse.

Swan: “Don’t you think the little Valentine’s been bluffing long enough?”

Swan: “Missed me? Speak. Say something.” Daisy: “My hair’s going gray.” Swan: “My gray-haired teenager. (Both laugh.) Welcome back. Alright here’s the schedule . . .” Daisy: “Ready to give the devil his dues?”

“Asking to play rough again? You’ll get up and if you don’t you’ll starve and if you starve I’ll sue you!”

You don’t cost me money, you make it!

“The picture is a big investment. I want it finished. Afterward, I don’t care what happens to you. There’s more where you came from. I’ll just write you off.”

Daisy awkwardly — almost comically — attempts “suicide” with her gas oven.

But first the phone rings . . .

Then, her nurse returns to fetch a book she had forgotten . . .

“Miss Clover, I have a favor to ask you for my sister, she’s your greatest fan, she’s just dying for your autograph!”

At this point, Daisy’s voiceover commentary that was heard at the beginning of the film returns. It was originally intended to be used throughout the film, but was cut before the first preview in October of 1965:

“Here’s the situation. I’m pushing seventeen and I’m, uh, America’s Little Valentine. I was married for one day, then I got insulted and divorced. The prince of darkness took me in his arms. And I almost gave myself ‘the works.’ But I haven’t let it go to my head. I’m still the same, happy, adjusted, polite young lady. And I’ll bet my simple healthy instincts against yours any day.”

She leaves the gas oven on and door open, with the stove top flame still burning . . .

“Hey, what happened back there?” “Someone declared war!“

I’ve always found the ending to the film unsatisfying. Daisy’s newfound “freedom” seems forced, and the reinstatement of Daisy’s “narration” in the final sequence is insufficient to explain her change. Maybe the deleted portions of her commentary would have provided the missing pieces to the puzzle, but I’m doubtful.

In the novel, Daisy eventually completes the last few scenes on her unfinished film for Swan. The movie bombs, Daisy doesn’t care, and buys out her contract for something less than six figures. Living on her trust fund, she gets pregnant, decides to have the baby and moves to New York City. After finding an apartment and a coterie of good friends in Greenwich Village, she spends a half-dozen years enjoying life, her little girl, Myrna, and not missing her career. Eventually, the urge to sing comes back, culminating in very unexpected success, not in the movies, but as a concert singer, with nearly all her old acquaintances reappearing for her opening night in Atlantic City, including Wade and his partner Malcolm, sister Gloria, and both Swan and Melora, to pay homage to the talent — and perseverance — of Daisy Clover.

* * *

Inside Daisy Clover premiered in New York at Radio City Music Hall in December, 1965, allowing the film to qualify for the Academy Awards for that year; it received a general U. S. release the following February. Among the major news publications, it was generally panned. It is not a great film. At best, it can be (and has been) called a good but uneven film, with powerful moments interspersed with periods of torpor, a “stiffness” that Redford has commented upon, a heavy silence that can work in the films of Kubrick or Bergman, but does not work in furthering the essential narrative of “Daisy.”

The film lacks sufficient humor to offset its many dark moments, and the comic antics of Daisy in the two sequences that bookend the film (which also retained Daisy’s off-screen narration originally intended for use throughout the film) don’t work particularly well. Unlike the novel, which gives us a consistently funny, irreverent Daisy Clover, one who is actually a bit irritating in her “non-conformity,” the film Daisy is vulnerable. We care about her more than in the novel, especially as we watch her being battered to a catatonic state. In the film, Daisy’s silence comes from her total breakdown — it is a result, a reaction. In the novel, it is largely a ruse. She’s fed up, gets up out of bed, finishes the film and leaves for New York — she doesn’t blow up anything, and she refuses to look back.

Inside Daisy Clover is not a musical, but it is a movie about a singing movie star. Music is at the core of Daisy’s narrative, and the complex score of André Previn (his final complete motion picture score) does as much to enhance the film as any of the performances or the cinematography. Of the three production numbers in the film, one was cut, and another was repeated twice, in different arrangements. One of the high points of the film is “The Circus is a Wacky World” sequence. It is among the most inventive and cinematically interesting musical production numbers of the period, even when compared to full-fledged musical films. This is due to the staging and Wood’s enactment, rather than the song itself.

The other remaining production number, “You’re Gonna Hear From Me,” is a bombastic anthem (covered not surprisingly by Barbara Streisand) that if heard only once in the film would be more than enough. Yet we get three different arrangements of it. This feeling of domination by one number was likely exaggerated when a “middle” production number, “A Happy Song,” aka “The Back Lot Kid,” was cut completely to help shorten the film’s length from more than two and a half hours to two hours and eight minutes, prior to the first preview in October in Los Angeles. This became the final cut of Inside Daisy Clover that premiered in New York in December, and was released nationally in February, 1966.

The other remaining production number, “You’re Gonna Hear From Me,” is a bombastic anthem (covered not surprisingly by Barbara Streisand) that if heard only once in the film would be more than enough. Yet we get three different arrangements of it. This feeling of domination by one number was likely exaggerated when a “middle” production number, “A Happy Song,” aka “The Back Lot Kid,” was cut completely to help shorten the film’s length from more than two and a half hours to two hours and eight minutes, prior to the first preview in October in Los Angeles. This became the final cut of Inside Daisy Clover that premiered in New York in December, and was released nationally in February, 1966.

The sequence that has received the most comment over the years since the film was released is the one that follows the “Circus” number and The Dealer’s death: Daisy’s dubbing booth “breakdown.” It is a brilliant amalgam of film and sound editing with Wood’s searing, frightening and all too real depiction of a total emotional collapse. As Daisy’s mind falls apart, the dubbing count-in continues to beep and flash on-screen relentlessly as the black and white image of a clowning Daisy leers back into the booth, is reflected on the glass, and mocks the real face of Daisy pressed hard against the window, distorted in anguish.

“I felt close to Daisy,” Natalie Wood told an audience at the San Francisco Film Festival in October, 1976, where she was being honored with a career tribute. Years after Inside Daisy Clover, she would explain that she was drawn to the role like no other since she played “Judy” opposite James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause in 1955. “Clover” was a film that, as Suzanne Finstad described in her bio of Wood, “she wholeheartedly believed would move her away from frothy romantic comedies back to the ‘golden world’ of [directors Elia] Kazan and [Nicholas] Ray,” the men who had directed her in Splendor in the Grass (1961) and “Rebel.”

With the exception of the opening sequence, Natalie Wood’s performance is powerful, often brilliant — certainly extraordinary compared to her contemporaries who are typically considered more accomplished or who received more accolades. Most remarkable is her performance over the last third of the film. It is a nearly silent performance, face, hands and body convey virtually all the meaning without words. Wood had worked with directors such as Kazan who had emerged from the New York stage, and she had certainly been exposed to the “method” school of acting through her work with Ray and with James Dean. But having acted in films from the age of 5, she had to fight the tendency to give the conventional performance of a classic Hollywood “movie star actor”- in other words, an actor playing themselves — rather than inhabiting a fully realized character. Suzanne Finstad quotes Robert Redford who explains the contradiction:

“There’s always that veneer of a Hollywood ‘star’ performance, giving the audience what you’ve learned works well. But there wasn’t a whole lot of that [by Wood as Daisy] . . . particularly if you could break through that sometime shield that would come over her — ‘I’m giving you my Natalie Wood performance.’ When you could break through that, which we did, you got in touch with what was really the best of her, which was this totally alive quality . . . I wouldn’t have expected a Hollywood movie person to be that dedicated to want to go for the craft, and she did . . . She really worked hard, she got herself completely into the role.”‘ Robert Redford, to Suzanne Finstad in Natasha: the biography of Natalie Wood.

Gavin Lambert as the author, knew “Daisy” better than anyone and was on the set to watch Wood recreate the character for the cameras. Yet to him, acting remained a mysterious art:

“I had an almost daily opportunity to watch Natalie at work. But as George Cukor once said, ‘Real talent is a mystery, and people who’ve got it know it. The very best actors never talk very much about acting itself-and above all they never talk about it until they’ve done it.’ This was certainly true of Natalie . . .” Gavin Lambert, Natalie Wood: a Life.

Wood had several problems with “Clover” during filming and in post-production. The first was unavoidable. She had long harbored a not-so-secret desire to be a singer, and had a pleasant, but very average singing voice, hardly suitable for a professional vocalist. Yet she was unrealistic about her capabilities. She had not the remotest ability to pull off the vocal pyrotechnics required by the operatic score of West Side Story, nor did it make sense to use her vocals as Daisy. The entire premise of Daisy’s rise to stardom is based upon her amazing ability as a singer (she won a movie-studio talent contest without even submitting a photo of herself). Though Wood was able to use her own singing voice in Gypsy, the character of Louise was a girl with no apparent talent — until she learns to strip. Wood’s light, untrained singing voice was ideal for that part. Not so for Daisy Clover. The only vocal of Wood’s that was kept for “Clover” was the eight bar intro to the screen test version of “You’re Gonna Hear From Me” with simple piano accompaniment. The remainder of that number, and all of the rest of the vocals in the film, were dubbed by a professional singer.

A more serious problem, for both Wood and Lambert, was the elimination of her off-screen narration for all but the opening and closing scenes of the film. In the novel, Daisy’s first person narration is frequently ironic, wry and always pithy — Wood and Lambert felt it was important in defining Daisy’s character in the film. Wood told Lambert, and the audience at an AFI seminar in 1979, that she felt half of her performance was lost with deletion of the voice-over. Judging by what remains, the surviving bits could have been cut, and the result, in my opinion, would be a slight improvement. With the narration, an “all or nothing” approach might have been best. But a rough cut of the film was well received at a sneak preview in Los Angeles, and the changes were kept.

The film premiered at Radio City Music Hall in New York during Christmas week, 1965, and according to Lambert, it’s poor reception by the media was “a painful jolt” to him and to Natalie Wood. But she had already moved on emotionally and professionally. Pre-production on her next film had begun in October. That film, This Property is Condemned, would give her another opportunity to prove herself in a film and role unlike any she had previously attempted. But as Lambert noted in his biography, there was an uplifting coda to the tale of Daisy Clover a decade after its original release when Ronald Haver of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art programmed a series of films “about Hollywood:”

“[Haver] asked me to invite Natalie to the screening of Daisy Clover. ‘I don’t know, what do you think?’ she said. I thought we should accept because Haver liked the movie and thought it was time for a reassessment. So we went. The audience reaction was enthusiastic, she received a standing ovation, and when we talked with various people afterward, it was clear that in spite of the damaging cuts, the movie had appealed to them in the way all of us had intended, as an ironic fable.”

* * *

Source: https://t-tees.com

Category: WHO