Omar Vizquel played more games at shortstop than any other man in the history of baseball. His career spanned four decades and 24 seasons, over which he won 11 Gold Gloves. Vizquel will be on the Hall of Fame ballot for the seventh time this December and is seeing his chances at the Hall of Fame disappear because of two scandals involving domestic violence and sexual harassment.

Prior to the two “character clause” issues, the center of the debate about Vizquel’s worthiness for a plaque in Cooperstown was between the community of sabermetricians and people who follow their instincts when evaluating a player’s Hall of Fame candidacy. Essentially, it was a WAR test vs. an eye test. Now it’s all about the character clause.

You are viewing: How Many Golden Gloves Did Omar Vizquel Win

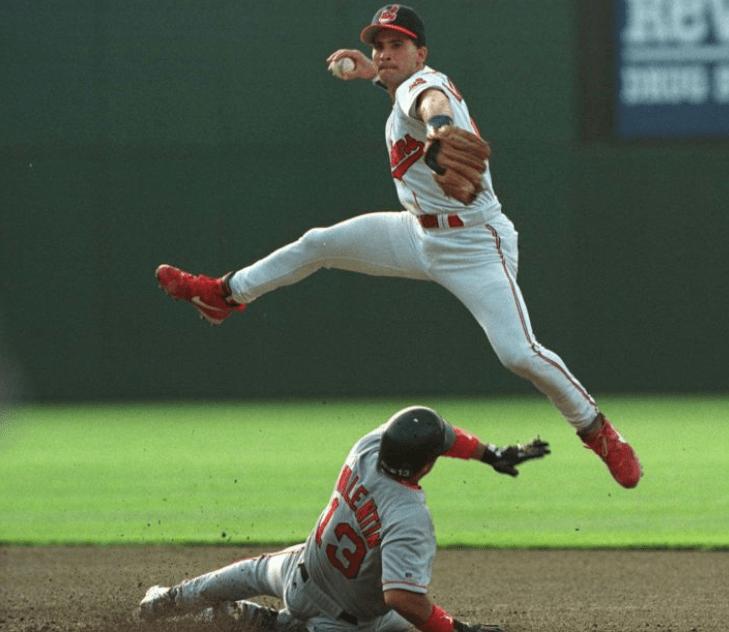

Vizquel, a flashy defensive player at shortstop, was considered the natural heir to the great Ozzie Smith. Omar and Ozzie. Vizquel and the Wizard. The Viz and the Wiz. Ozzie was known for his signature back-flips. Omar was known for his acrobatic play and, in particular, his ability to cleanly field a bouncing ball with his bare right hand and throw to first base in one fluid motion.

In his first year on the BBWAA (Baseball Writers Association of America) ballot, the Venezuelan Vizquel got 37% of the vote. That’s far short of the 75% needed to be granted a Cooperstown plaque but it’s a fairly good tally for a first-year candidate. Excluding those still on the ballot, in the history of the Hall of Fame voting, only Steve Garvey, Curt Schilling, and Roger Clemens got more than 37% of the vote on their first ballot without eventually getting elected to the Hall of Fame (Barry Bonds clocked in at 36% in his first year).

As a comparison, Luis Aparicio, a fellow Venezuelan shortstop, got 28% of the vote on his first ballot in 1979. Five years later he was in the Hall of Fame.

Vizquel’s BBWAA Vote Share Craters

In 2019, Vizquel crept up to a 43% tally. In 2020, he received the support of 52.6% of the electorate. In January 2021, however, his vote percentage sagged to 49.1%, a result of the breaking news in December 2020 that his wife Blanca had accused him of multiple instances of domestic violence.

Then, in the summer of 2021, we had more disturbing news about Vizquel’s character. In a civil lawsuit, an autistic man accused Vizquel of sexual harassment. The man was a batboy when Vizquel was the manager of the Birmingham Barons, the AA affiliate of the Chicago White Sox. The details of the allegations are lurid and disgusting.

As a result of the sexual harassment allegations, Vizquel’s support among the voting members of the BBWAA fell off a cliff. He received just 23.9% of the vote, a drop of 25.2%. In the modern history of voting (starting in 1966), Vizquel blew away the record of year-to-year loss in the vote, which had previously belonged to Luis Tiant.

El Tiante got 30.9% in his first year on the ballot (1988) but dropped to 10.5% in 1989, a result of an exceptionally strong list of first-time-eligible players (Johnny Bench, Carl Yastrzemski, Gaylord Perry, and Fergie Jenkins). Only seven players since 1966 have lost as much as 15% of their voting support from one year to the next.

WP Table Builder

Incidentally, the biggest drop for a player’s BBWAA vote share belongs to Charles “Chief” Bender, who got 44.7% of the vote in 1947 but just 4.1% in 1948. There was a reason for this, however. The Hall instituted a rule change for the 1948 vote, indicating that only players from 1922 to 1946 should be considered. Bender, whose career ended in 1917 with the exception of a one-inning cameo in 1922, wasn’t eligible but got five votes anyway. The right-handed pitcher, a three-time winner of the World Series with the Philadelphia Athletics, was voted into the Hall in 1953 by the Veterans Committee.

Anyway, in the 2023 voting cycle, it got even worse for Omar Vizquel. He received just 19.5% of the vote. It now seems nearly impossible that he’ll clear the 75% in his next four turns on the ballot.

Regarding his performance on the field, Vizquel had a devoted legion of backers who feel like he was the best defensive shortstop not named Ozzie that they ever saw. At the same time, he has always had a large contingent of critics who claim that his defensive prowess was overrated and that he wasn’t nearly proficient enough with the bat to merit a Cooperstown plaque. Despite the prior history that predicted that Vizquel would climb above 75% in upcoming BBWAA votes, the ballots of 2022 and 2023 have changed all of that.

This piece will share a recap of Vizquel’s career and take a deep dive into the baseball arguments for/against his Cooperstown candidacy before circling back to the support he’s lost from the BBWAA writers.

Cooperstown Cred: Omar Vizquel (SS)

7th year on the BBWAA ballot (received 19.5% of the vote in 2023)

- Mariners (1989-93), Indians (1994-2004), Giants (2005-08), Rangers (2009), White Sox (2010-11), Blue Jays (2012)

- Career .272 BA, 404 SB, 82 OPS+, 45.6 WAR (Wins Above Replacement)

- 2,877 career hits (5th most ever among MLB shortstops, behind Jeter, Wagner, Ripken, and Yount)

- 11 Gold Gloves, 2nd most ever for a shortstop (Ozzie Smith had 13)

- Career: .9847 fielding percentage (best ever for all MLB shortstops) (min. 1,000 games)

- Led league in fielding percentage 6 times

- 2,709 games played at shortstop (most all-time)

- 1,744 career double plays turned (most for SS all-time)

(cover photo: Cleveland Plain Dealer/Chuck Crow)

Portions of this piece were originally published in October 2017 and have been updated in advance of the 2024 vote.

Omar Vizquel: Early Years

Omar Vizquel was born on April 24, 1967 (one day before the author of this piece, incidentally) in Caracas, Venezuela. The Seattle Mariners signed Vizquel for $2,000 in 1984.

The young switch-hitter spent five seasons in the minor leagues before making his MLB debut with the Seattle Mariners on April 3, 1989, 21 days shy of his 22nd birthday. Vizquel’s debut occurred on the same day as the major league debut of his highly heralded teammate, Ken Griffey Jr.

In his rookie campaign, Vizquel mostly fielded his position well but contributed virtually nothing offensively, hitting .220 with a .273 on-base% and a .261 slugging% (translating to a park-adjusted OPS+ of 50). Based on OPS+ (in which 100 is average and, thus, 50 is WAY below average), it was the second-worst offensive season in the first 14 years of Mariners’ baseball for a player with at least 400 plate appearances, second only to the 1979 campaign of Mario Mendoza.

Because of an injured knee, Vizquel didn’t join the Mariners in 1990 until July 5th. In a half-season in ’90 and a full season in 1991, Vizquel emerged as one of the best defensive shortstops in the game but still contributed very little with the bat. In his first three seasons, with 1,198 plate appearances, the young shortstop managed just a .230 BA, .290 OBP, and .283 SLG, which translates to a woeful OPS+ of 60.

“Little O” quickly gained a reputation for being a slick fielder as a young player. It’s difficult to fully trust defensive metrics (especially prior to 2002) but, according to the “Zone Runs at SS” metric on Baseball-Reference and FanGraphs, Vizquel was a top 4 defensive shortstop in the American League in each year from 1990 to 1993.

Embed from Getty Images

Breakthrough Season and Emergence as Defensive Star

In 1992, Omar Vizquel had a mini-breakthrough with the bat, hitting .294. He regressed a bit offensively in 1993, his fifth year in the majors, but his reputation as a sterling defender was growing. It was in ’93 that Vizquel won the first of his nine consecutive Gold Gloves.

The Mariners weren’t a very good team in Omar’s years there but these were the early years of ESPN’s Baseball Tonight, affording fans throughout the nation the opportunity to see his or any other player’s spectacular plays on a nightly basis, including West Coast games in-progress.

In April 1993, the nation got the opportunity to see Vizquel’s signature defensive move on the last out of Chris Bosio’s no-hitter on April 22. Click here to watch Vizquel’s bare-handed catch and throw to preserve the no-no.

Trade to Cleveland

After the ’93 season, Omar Vizquel was traded to Cleveland in exchange for another Latin American shortstop (Dominican-born Felix Fermin) and first baseman Reggie Jefferson. Let’s just say that trade was not a good one for the Mariners.

Vizquel spent 11 productive seasons with the Indians, winning seven Gold Gloves while appearing in the post-season six times and the World Series twice, though his teams never won the Fall Classic. The Indians were a team that was filled with offensive stars (Albert Belle, Jim Thome, Manny Ramirez, Eddie Murray, Kenny Lofton, and Carlos Baerga). Being a solid contributor defensively was just what the doctor ordered and Vizquel was that.

On the 1995 team (which went 100-44 in a strike-shortened season and made it to the World Series before falling to the Atlanta Braves), Vizquel was installed by manager Mike Hargrove as the Tribe’s 2nd-place hitter, Although hardly a star offensively, Vizquel made modest contributions, setting career highs with 6 home runs, 28 doubles, 56 RBI, 87 runs scored and 29 stolen bases. However, in the ’95 post-season, Vizquel struggled mightily with the stick, hitting just .138 in 58 at bats.

In 1996, Vizquel established career highs for his entire slash line (.297 BA/.362 OBP/.417 SLG) while scoring 98 runs. His offensive numbers declined slightly in 1997 but he still contributed 89 runs scored, helped by a career-high 43 stolen bases. The ’97 Indians returned to the Fall Classic but fell short again, this time in 7 Games to the Florida Marlins. Again, the Tribe didn’t get much offensively from their shortstop; Vizquel hit just .233 with a .569 OPS in the playoffs.

All-Star Omar Vizquel

In 1998, with Hargrove skippering the team, Omar Vizquel made his first All-Star squad. With Derek Jeter, Alex Rodriguez, and Nomar Garciaparra re-defining the position, it was not easy for an American League shortstop to make the Mid-Summer Classic in the late 1990s.

Still, Vizquel made it back in ’99, in which he had the best year offensively in his career, establishing 24-year highs across his slash line (.333 BA/.397 SLG/.436 SLG), along with 42 steals and career bests in hits (191) and runs scored (112). His WAR of 6.0 was good enough for the 11th-best in the entire American League (for both pitchers and position players). For his efforts, Vizquel finished 16th in the MVP voting.

1999 was also the season in which Vizquel welcomed a future Hall of Fame double-play partner in switch-hitter Roberto Alomar. Like Omar, Robby dominated the Gold Glove Awards during this era, winning 10 awards in 11 years between 1991-2001. In the three years that the slick-fielding duo played together (1999-2001), they became the first keystone combination to win three straight Gold Gloves together since the 1970s, when Joe Morgan and Dave Concepcion were each awarded the hardware for four years in a row in the N.L. (1974-77); Bobby Grich and Mark Belanger also did it in the Junior Circuit from 1973 to ’76.

In the years that followed his signature 1999 campaign, Omar was unable to maintain his All-Star batting form and his base-running game declined as well. After averaging .300 with 39 stolen bases per year from 1996-99, he fell to .269 with 15 steals per year from 2000-03. Still, in 2002 he made his third and final All-Star squad in a season in which he set career highs with 14 HR and 72 RBI. However, 2002 was the year that his streak of 9 straight Gold Gloves came to an end (Rodriguez won it in 2002 and ’03).

Final Years in San Francisco, Texas, Chicago, and Toronto

After a solid age-37 campaign (in 2004), Vizquel left the American League, signing a 3-year contract with the San Francisco Giants, where he would win his final two Gold Gloves. He spent four seasons in the City by the Bay before spending his final four seasons bouncing from the Rangers to the White Sox to the Blue Jays.

In his first two seasons with the Giants, besides winning the Gold Glove hardware, Vizquel was respectable offensively. However, starting in 2007, despite still playing well in the field, Little O started to become an offensive liability. Over 6 seasons (as a mostly part-time player), he posted a woeful slash line (.250/.305/.310), which translated to a 63 OPS+. According to Stathead’s Play Index (as ranked by OPS+), Vizquel was the third least effective offensive player in baseball for that six-year period, this for players with at least 1,500 PA.

Vizquel retired after the 2012 season at the tender age of 45.

Making the Hall of Fame Case for Omar Vizquel

I never considered Vizquel to be a Hall of Fame player but many people do. I was struck by a column I read in January 2017, shortly after that year’s vote was announced, in which espn.com’s Jayson Stark said that Vizquel would get a checkmark next to his name on his 2018 Hall of Fame ballot.

Stark’s primary case was, of course, about Vizquel’s defensive prowess, that he was the most sure-handed shortstop of all time. Stark acknowledged that Vizquel’s defensive range statistics showed that he actually wasn’t a modern Ozzie Smith but that “nobody was.” Stark noted that Vizquel had three seasons in which he played at least 140 games and had less than 5 errors, which is more than all other shortstops since 1900 combined.

Stark ultimately did not vote for Vizquel in 2018 (a casualty of the 10-player limit) but his column woke this writer up to the idea that Omar’s Cooperstown candidacy should be taken seriously. With less-stacked ballots, Vizquel did get Stark’s support in 2020 and 2021 but the writer did not vote for him in 2022 because of the domestic violence and sexual harassment allegations.

There are some lists upon which Vizquel sits that speak positively to his Hall of Fame candidacy:

- He’s one of only 22 players to last long enough to accumulate over 12,000 plate appearances. All of the others are in the Hall of Fame except for gambling-tainted Pete Rose, PED-tainted Barry Bonds, Rafael Palmeiro, Alex Rodriguez, Adrian Beltre (who will be on the 2024 ballot), and Albert Pujols (2028 ballot).

- Omar is one of 7 position players to win at least 11 Gold Gloves. The only one not in the Hall is Keith Hernandez, who played first base, a much less important position on the defensive spectrum. (Hernandez is Cooperstown-worthy, in my humble opinion).

- Vizquel is one of 11 shortstops to get over 2,500 career hits. All of the others (except for A-Rod) are in the Hall of Fame.

- He had 2,877 career hits. The only players with more who do NOT have a plaque in Cooperstown are either ineligible (Rose), not YET eligible (Ichiro Suzuki, Beltre, Pujols, Miguel Cabrera), or tainted by PEDs (A-Rod, Bonds, and Palmerio). With the election of Harold Baines to the Hall in 2019 by the Today’s Game Committee, Vizquel is the only eligible non-scandal-tainted player with over 2,800 hits who is not in the Hall.

Ozzie v Omar

Anyway, if Ozzie Smith is the most germane comparison for Omar Vizquel, let’s stack up their numbers against each other, remembering of course that, for each, it’s the more difficult to measure defensive skills that are at the core of their greatness. Just going by the hardware, Ozzie finished his career with 13 Gold Glove Awards, two more than Omar’s 11.

First, the offensive profiles:

WP Table Builder

Well, if you just look at that, Omar Vizquel looks pretty good.

Similarity Scores

Omar Vizquel’s offensive statistical profile, in fact, matches up very well in comparison to multiple already-enshrined Hall of Fame shortstops. On Baseball Reference, every player profile contains something called “Similarity Scores.” This was a Bill James invention designed to simply compare the statistical profiles of two players. If you are interested in the details, the methodology is linked here.

Anyway, here is the list of the top 8 players with the most “similar” offensive profiles to Omar Vizquel:

- Luis Aparicio

- Rabbit Maranville

- Ozzie Smith

- Bill Dahlen

- Dave Concepcion

- Luke Appling

- Pee Wee Reese

- Nellie Fox

With the exception of Concepcion and Dahlen (a turn of the 19th-century player), all of the most “similar” players have plaques with their names on them in the Hall of Fame. As for Dahlen, Bill James wrote (in his Bill James Handbook 2019) that he is the best position player who is eligible for the Hall but not in it.

The Case Against Omar Vizquel for the Hall of Fame

With 11 Gold Gloves and nearly 2,900 hits as a shortstop, that should be enough for a Hall of Fame plaque, right? Well, not so fast, there are three major problems.

- Some of the defensive metrics don’t back up Vizquel’s reputation as an all-time premier defender. I realize that this will be a point of contention for many people since defense is more difficult to quantify numerically.

- On balance, he was not helpful to his teams offensively.

- Finally, while the game’s coaches and managers gave Vizquel all of that hardware shaped like a glove, the writers who covered the sport did not accord that same respect when it came time to cast MVP votes. Only once (in 1999) did Vizquel receive any MVP consideration at all. In addition, he only made 3 All-Star teams in 24 years.

Read more : How To Customize Goalkeeper Gloves

We’ll go through each of these objections one at a time, starting with the criticism that his defense wasn’t perhaps as great as our memories of it.

The Basic Defensive Statistics

At the most basic level, there is this: as of the end of the 2022 season, Omar Vizquel’s fielding percentage of .9847 is the best in the history of baseball for shortstops. Considering that the Baseball-Reference page that lists him at #1 only requires 500 games played to be eligible for the list, his spot on top is even more impressive because he maintained that success over the course of 2,709 games.

This statistic is the one that most certainly forms the primary basis for the 11 Gold Gloves.

Vizquel wasn’t as sure-handed in his 20s as he would become later in his career. In his first eight seasons, his fielding percentage was .979, still excellent but only .008 better than the league average. Since turning 30 years of age, however, he posted an astounding .988 fielding percentage. That might seem like a trivial difference, but it isn’t. It’s remarkable.

- 1989-1996: in 1,008 games played, Vizquel committed 95 errors at shortstop.

- 1997-2012: he committed just 88 miscues in 1,701 games at the position.

Range Factor

As we’ve learned over time, there is much more to defensive excellence than not making errors. Omar was never at the top when it comes to metrics that relate to his range factor. Bill James made us aware of Range Factor as early as the 1980s in his annual Baseball Abstract, must-reads for yours truly as a teenager. Unlike most of the modern metrics, Range Factor is pretty simple to understand:

Range Factor per 9 innings = 9 *(putouts + assists)/innings played

In his career, Vizquel’s Range Factor per 9 innings was 4.62. The league average over those 24 seasons was 4.61. This essentially means that Vizquel, over his entire career, was merely “average” when it comes to how many plays per 9 innings he was involved in.

What makes this metric meaningful in conjunction with Fielding Percentage is that a player with a super-high Fielding Percentage but a lower Range Factor can be fairly viewed as a player either with limited range or a cautious player. Having watched many of his games over the years, I’m inclined to view Vizquel as the cautious type.

This is not necessarily a bad thing. Many infielders, in a futile attempt to make an impossible play, throw the ball away. Sometimes it’s better to eat it and allow the runner to reach base. My point is that, statistically, a super-high fielding percentage combined with a league-average range factor is indicative of a smart player who makes lots of plays but doesn’t hurt his team by making foolish throws when there’s no chance for an out.

Embed from Getty Images

Taking a Deep Dive into WAR

Anyway, advanced metrics available to us now combine these factors into one number. A brief warning to those not statistically inclined: this is a deeper dive into the weeds than I usually go. If that dive is too deep for you, feel free to scroll down to “The Art of the Bunt.”

In the next table, there will be two metrics shown:

- “WAR Runs Fielding”: from Baseball-Reference, the number of runs better or worse than average the player was for all fielding plays. This is one of the five elements that make up a position player’s WAR, the others being batting, base-running, double-play avoidance, and positional adjustment.

- “Defensive WAR”: also from Baseball-Reference, this is a “defense only” Wins Above Replacement calculation, adjusted for each position on the defensive spectrum.

I’m sharing the Top 15 for each category dating back to any player who debuted in 1902 or later. If you’re wondering why I picked the somewhat arbitrary year of 1902, it was to exclude Hall of Famer Bobby Wallace, who debuted in 1894. It’s nothing against Wallace; I just wanted to limit this to the modern game. Also excluded by choosing 1902 instead of 1901 was George McBride, a lifetime .218 hitter who would not have made the top 10 in the defensive metrics and is not germane to this discussion.

WP Table Builder

As an aside, if you’re wondering why Jack Wilson and Rey Sanchez crack the top 15 in WAR Runs Fielding but not in dWAR, it’s because of longevity. The dWAR metric gives players credit merely for playing the position of shortstop. Therefore, the more games you play, the more “position points” you get. However, this does mean that Wilson and Sanchez were really spectacular defensive players and play for play, better than Vizquel (if you believe the metrics).

Longevity is important and most of the players on the Defensive WAR (dWAR) Top 15 list are in the Hall of Fame. Therefore, it’s logical to conclude that Vizquel might belong in Cooperstown as well. Anyway, the numbers here generally back up Vizquel’s defensive reputation but there are some other players on this list who are not Hall of Famers, most notably Mark Belanger. It’s worth a moment to look at that.

The Offensive Record

So, let’s look at a few offensive numbers for the top 7 members of the dWAR leaders, the Hall of Famers on the list, and also two members of Omar Vizquel’s “similarity score” list (Concepcion and Appling). We’ll rank the players by OPS+ (on-base% + slugging% adjusted for ballparks and seasons).

WP Table Builder

First of all, we can see why comparing Mark Belanger to a prospective Hall of Fame shortstop with a defensive resume is not needed. The longtime Orioles shortstop may have won 8 Gold Gloves but a .228 career batting average and 68 OPS+ do not cut it.

What jumps out here regarding our man of the hour is that Vizquel’s 82 OPS+ is really poor but that it’s identical to two Hall of Fame shortstops (Aparicio and Maranville) and just a few ticks below that of the Wizard of Oz. So let’s shorten the list to those at the lower end of the chart with respect to offensive productivity and, if we can conclude that Vizquel is in the same class as the others, then perhaps he belongs in the Hall.

The chart below is a “WAR” chart. It shows each player’s overall WAR, their offensive WAR, and also two key components that go into the offensive component (“runs above or below average batting” and “runs above or below average for base-running.”) The latter includes stolen bases, stolen base success percentage and extra bases taken, such as going from first to third on a single.

I’m adding one other player to the conversation here. It’s the longtime member of the 1970s Oakland A’s dynasty, Bert Campaneris. He, like Vizquel, played a great many years on a team of superstars. Campy’s presence is germane because he is the only Hall of Fame-eligible shortstop in the modern era with a WAR of over 50 who is not enshrined in Cooperstown.

The Components of WAR

WP Table Builder

OK, so now we understand, whether you believe in the metrics or not, why WAR puts Omar Vizquel 10 wins below his boyhood idol Aparicio (another Venezuelan product). Aparicio was better as a hitter and much better as a base-runner. Meanwhile, Ozzie Smith was also a superior batsman, a better base-runner, and, of course, the owner of off-the-charts defensive metrics. Hence why Ozzie was a first-ballot Hall of Famer and Vizquel has been the subject of what may now seem to you (the reader) an endless discussion of the topic. It’s also a fair question to ask whether Campaneris (who won three World Series titles) would be a better Hall of Fame choice than Vizquel.

As you can see from this and the previous chart, the player most truly similar to Vizquel is the Hall of Famer Maranville, who is often noted as one of those first half of the 20th century Hall of Famers who probably would not have made it through today’s stacked ballots.

For whatever it’s worth, Bill James, in a recently published series on his website, ranks Vizquel as the 37th-best shortstop of all time, well behind the others on this list. James ranked Ozzie 13th, Campaneris 26th, Aparicio 29th, Maranville 30th, and Concepcion one spot behind Omar at #38.

Embed from Getty Images

Other Offensive Ranks

I need to put some perspective on the “WAR runs from batting” number. Omar Vizquel’s negative 244.2 is really, really miserable, almost as miserable as Rabbit’s minus 228.6. Since 1901, there have been 220 shortstops who have accumulated at least 3,000 plate appearances. Of those 220, Vizquel ranks #210 with respect to WAR runs gained or lost due to batting. That’s the 11th to last in 122 years of baseball. That may seem hard to fathom for a man who racked up 2,877 hits but 79% of those hits were singles and Omar made a lot of outs along the way as well.

There are 36 players who finished their careers with between 2,700 and 2,999 hits. Of those 36 players, Vizquel is last in OPS and OPS+, by a lot. He made the most outs in this group.

Of the 20 players with over 12,000 career plate appearances, only he and Barry Bonds failed to make it to 3,000 hits (but Bonds walked 2,558 times in his career, by far the most ever).

2,877 hits put Vizquel in 44th place all-time. The 44th place-holder on the all-time home run list is Jason Giambi, who is one spot behind Dave Kingman. I’m sorry but 2,877 hits are not a legitimate offensive Cooperstown credential, not with an 82 OPS+.

The Base-Running Record

In addition to his woeful offensive record, you might be surprised that Omar Vizquel gets no credit from WAR for his base-running ability, despite his 404 career stolen bases. So, let’s stack him up against the others (excluding Maranville because Caught Stealing statistics are not complete from the years that he played).

WP Table Builder

Well, here it is in a nutshell. Vizquel was successful only 71% of the time when attempting to steal. Any base-runner who is successful less than 75% of the time is not really helping his team. Aparicio and Ozzie, both near 80%, were assets on the bases in a way that Omar was not.

In addition, taking an extra base was not something that Vizquel excelled at. An Extra Base Taken (XBT) rate of 42% is a really low number for a player with good speed. It does play into the narrative of Vizquel as a somewhat cautious player who did not like to make mistakes, either an error in the field or by getting thrown out on the bases.

Incidentally, it did occur to me that Omar might have been overly cautious on the bases because he spent his best years in an Indians’ lineup that was packed with home run hitters. However, the numbers don’t back up that notion. Vizquel’s rate of extra bases taken was 44% in his 11 years with Cleveland. However, teammate Kenny Lofton had an Extra Bases Taken rate of 58% in 10 years, which included one season in Atlanta. Heck, Jim Thome had an XBT rate of 36% with the Tribe; Manny Ramirez was at 39% and Albert Belle’s was 47%, better than Vizquel’s XBT rate.

The Art of the Bunt

There is one offensive statistic in which Omar Vizquel reigns supreme. As a reader pointed out to me a couple of years ago, Vizquel was the Sultan of Sacrifice. With 256 sacrifice hits (bunts) and 94 sacrifice flies, Vizquel has the most combined sacrifices (350) since 1954, the first year Baseball Reference measures sacrifice flies. Ozzie Smith is a distant second with 277.

Vizquel started 2,181 games while batting either 2nd or 9th. Both batting order positions are the ones in which managers traditionally have employed a bunt to move a runner up a base. With the exception of pitchers hitting in the National League, the sacrifice is slowly becoming extinct because modern metrics generally show that it’s not worth giving up an out to move a runner up one base. Still, Vizquel was asked to do this a lot.

Besides his 256 sacrifice hits (bunts), Vizquel had an additional 151 base hits in his 509 plate appearances defined as having a “bunt” trajectory.

Baseball-Reference’s Stathead has splits for a hit or out trajectory going back to 1988, the year before Vizquel’s debut. During that time 35 players had at least 200 plate appearances that were characterized as bunts. Vizquel’s 151 bunt hits are the 5th most (behind Juan Pierre, Lofton, Brett Butler, and Otis Nixon). However, his batting average on bunts (.592) is the best of the 35. In case you’re curious, Omar is in good company here. Lofton is 2nd best with a .577 average on bunts; Roberto Alomar is 3rd (.572); Craig Biggio is 4th (.544). (Kind of neat that the top three were all teammates in Cleveland).

Of course, we will never know the career batting average on attempted bunts by early players such as Eddie Collins, Willie Keeler, or Phil Rizzuto. We do know, for however you want to value it, that nobody since 1988 was able to accomplish more positive outcomes for his team by bunting than Omar Vizquel.

In 509 career bunt attempts, Vizquel moved the runner up 256 times and got a hit 151 times. That’s a positive outcome in 407 out of 509 tries for a success rate of 80%. That’s superb, the best “positive outcome” success rate of the 35 most frequent bunters.

The Bad News Splits

OK, we’ve established that Omar Vizquel was a superior practitioner in the art of the bunt. The next question I wanted to explore is whether there was some other good news in Vizquel’s splits that show some hidden offensive value in his lowly career .688 OPS.

Baseball Reference lists 40 players with at least 1,500 line drives between 1988-2022. Vizquel achieved a line drive off the bat in 18.1% of his career plate appearances, a solid number, better than all but 7 of the 40 studied players. The bad news is that his 1.599 OPS on line drives is 37th out of the 40 players. The overall MLB average is a 1.729 OPS on line drives.

It gets worse. 44 players have had at least 3,000 ground balls during the relevant 35 years. Vizquel’s batting average on ground balls was just .214, the 3rd lowest out of the 44 players. That’s a very low number for a fast player. By comparison, Ichiro Suzuki hit .286 on ground balls. Even the slow-as-a-turtle Albert Pujols hit .234 on grounders.

As for fly balls, one would not expect good results for Omar because he was not a power hitter. The results, however, are flat-out terrible. Of the 33 players with at least 2,500 fly balls since 1988, Vizquel’s .319 OPS is by far the worst. The 2nd worst number is Orlando Cabrera’s .470. 3rd worst? Jimmy Rollins at .570.

If you widen the study to look at the 225 players with at least 1,500 fly balls, Vizquel’s OPS is still last at .319, 41 points below Neifi Perez’s .360. Vizquel’s batting average on fly balls (.104) is also the lowest out of all of the 225 players. If you add Omar’s 85 sacrifice flies as a “positive outcome” for a fly ball, the “positive outcome rate” is still just 13%, the worst of all 218 players.

The conclusion? Vizquel was the best in the game at producing positive results on bunts but the worst on fly balls. The problem is that bunt plays account for just 4.2% of his career plate appearances while fly balls account for 26.4%, and ground balls 33.1%.

The Accolades Problem:

Summarizing what we’ve discussed, here are the arguments against Omar Vizquel for the Hall of Fame:

- Not a good hitter: his career batting average (.272) and on-base% (.336) were about league average; his slugging % (.352) was poor.

- Not a great base-runner: 404 career steals negated by 171 times caught stealing for a middling 71% success rate.

- Sure-handed defender but one with merely average range: his career Range Factor (putouts + assists) of 4.62 per 9 innings was barely above league average.

- Never in contention for an MVP award and only made three All-Star squads.

Read more : How Much Did John Glover Get Paid

Arguing in favor, it comes back once again to these three things:

- 11 Gold Gloves at one of the top two key defensive positions on the diamond.

- Highest fielding percentage at his position in the history of the sport.

- 2,877 hits, which is the most for any eligible player not in Cooperstown already except those tainted by scandal.

It’s the Gold Gloves that are key. They were conferred upon Vizquel by the collective will of the league’s players and coaches.

However, the BBWAA membership never saw fit to give Omar the same level of recognition when it came time to vote for the league’s Most Valuable Player each year. So finally, let’s look at Vizquel’s MVP problem, perhaps the biggest missing piece on his resume.

Never among the Most Valuable

As we’ve seen, in 24 big league seasons, Omar Vizquel’s best offensively was in 1999, when he hit .333, had a .397 on-base%, stole 42 bases, and scored 112 runs. Still, even though he also occupied a key defensive position and was part of a flashy DP combo with Roberto Alomar, when it came time to select the MVP, Vizquel finished just 16th in the voting. He was overshadowed by two of his teammates (Alomar and Manny Ramirez) who finished tied for 3rd.

All in all, Omar’s 16th-place finish put him just ahead of the legendary Matt Stairs, John Jaha, and B.J. Surhoff. Only one of the 28 voting writers conferred an MVP vote to Vizquel. It was Evan Grant of the Dallas Morning News, who gave him an 8th-place nod. (Incidentally, Grant did not vote for Vizquel in his first two BBWAA ballot appearances but did check his name on the less-stacked ballot of 2020 but withdrew his name in 2021 and 2022).

This is important: 1999 was the only time in his 24-year career that Omar Vizquel received even one MVP vote. Vizquel was considered one of the top 8-to-10 players in his league just once, and only one out of 28 writers had that opinion.

Now, regarding the MVP issue, it is fair to ask if there’s an anti-defensive player bias. So let’s look at that. The chart below shows the number of times that the Hall of Fame shortstops since 1931 have received MVP votes and made the All-Star team. Why 1931? It was the first year that both leagues voted for an MVP without interruption in subsequent years.

I’ve also included Jimmy Rollins, who is on the BBWAA ballot with Vizquel.

We’ll list the players in order of the number of career All-Star appearances.

WP Table Builder

We can see plainly that Omar Vizquel was never accorded even close to the same level of respect by the writers as other top shortstops in history when it came time to cast MVP votes or by the league managers when it was time to pick All-Stars. It’s not that the writers voting for MVP simply ignored defensive-oriented players. Every single Hall of Fame shortstop since 1931 received some MVP love at least 6 times in their career.

One more look at the Defensive Metrics

So this is the bottom line. The biggest selling point for Omar Vizquel for Cooperstown is his 11 Gold Gloves, which are the 2nd most by any shortstop not named Ozzie Smith. But Gold Glove voting is a mostly subjective process, conducted by the league’s managers and coaches. Using objective methodology, this final chart shows where Vizquel ranked in Defensive WAR (dWAR) during his 11 Gold Glove seasons.

WP Table Builder

Even if you are suspicious of retroactive defensive metrics (as I am), this is an amazing chart and almost impossible to disregard. In the 11 years that Omar Vizquel won a Gold Glove, he never led his league in Defensive WAR and only finished in the top four twice.

If Gold Gloves were handed out based on dWAR, he would have none instead of 11. Incidentally, Vizquel did finish second in dWAR in the A.L. in 1991 & 1992; he was second to Cal Ripken Jr., who won the Gold Glove in both of those years.

OK, so does that mean that dWAR is a useless statistic, or does it mean that Vizquel’s greatness was overrated? Well, by point of comparison, Ozzie Smith (the undisputed gold standard at the position) won the Gold Glove award 13 times. In those 13 seasons, he led the National League in dWAR (among shortstops) 10 times and finished 2nd the other three times. So, based on that information, it’s hard to simply dismiss the defensive metric dWAR as being categorically flawed.

The Wizard was famous for the acrobatic backflips that he performed to delight the crowd before the game. Vizquel also displayed an acrobatic flair in the field and reminded us all (players, coaches, managers, writers, and fans) just a little bit of the great Ozzie. He established his golden reputation early in his career and the reputation stuck with him. And he absolutely was an excellent defensive player.

I don’t profess to be an expert on how dWAR or “Total Zone Runs” are calculated but I think it’s likely that it underrates Vizquel’s sure-handedness, and his extraordinary ability to minimize errors. However, is it also possible that the official scorers throughout the league gave him, based on his reputation, the benefit of the doubt on the borderline “hit or error” scoring decisions? Yes, that’s very possible, even likely.

Vizquel was an excellent defensive player but he wasn’t so great that one can ignore that he was worse than mediocre when it comes to the offensive side of the game and just average as a base-runner.

The “Eye Test”

Despite the less than other-worldly defensive metrics and his obvious shortcomings with the bat, Omar Vizquel did quite well with the voters before his scandals, getting 52.6% on the 2020 ballot, which was the last one before the domestic violence allegation was made against him. That news broke in December 2020, after most writers had sent in their ballots, so he sagged only to 49.1%.

This is a brief sample of some of the things written in favor of Vizquel for the Hall of Fame in the years prior to the news of the domestic violence allegation.

“Yes, my small Hall includes Vizquel. Go ahead and torch me for that, but I believe that longevity matters — especially at the most grueling position on the infield — and there aren’t metrics that can adequately assess the transcendent joy he brought to anyone who watched him play.”

— Andrew Baggarly (The Athletic Bay Area, 12/30/19)

“I have two very simple Hall of Fame criteria: The first is the ‘see’ test. In watching a player for 10 or more years, did I say to myself: ‘I’m looking at a Hall of Famer?’ The four greatest fielding shortstops I ever saw were Vizquel, Ozzie, Luis Aparicio and Mark Belanger. Ozzie had the flair and the back flips, but Vizquel, for me, was the best. Made every play look easy.”

— Bill Madden (New York Daily News, 12/8/17)

“A consummate fielder — I said consummate — fielder, and teamed with Hall of Famer Roberto Alomar to form the best DP combo I ever saw. Yes, I am partial to defensive whizzes, and I refuse to apologize for it.”

— Bob Ryan (Boston Globe, 1/8/18)

“Face it, Vizquel’s was his generation’s Ozzie Smith, or the closest facsimile… Stats are important, and newer metrics that better compare players through different eras are valuable. But they are the sum of a player’s career. If you use numbers alone to shunt Vizquel into that mythical Hall of the Very Good, it’s a fair bet you did not see him play. Sometimes a man is a Hall of Famer because, well, he just is.”

— Henry Schulman (San Francisco Chronicle, 12/26/17)

If the eye test is enough for these writers, that’s fine. They’ve been covering the sport for a long time and have earned their Hall of Fame votes. Their eyes and the opinions formed by them represent a legitimate point of view. But these gentlemen, veteran baseball writers all, are part of a fraternity that almost never considered him one of the top 10 players in the league.

Remember, however, that these comments are part of the historical record that indicated that Vizquel was on track to eventually make the Hall of Fame. But that’s all changed.

Fall from Grace

With the second piece of shocking news regarding Vizquel (the lurid sexual harassment lawsuit) having been revealed in the summer of 2021, Vizquel’s support cratered to 23.9% in 2022 and dropped even further (to 19.5%) in 2023. As we’ve already documented, it’s by far the biggest nosedive in BBWAA support in the modern history of the vote (since 1966). Although neither allegation has been proven, there’s the old “fool me once, fool me twice” mantra that is clearly in play.

“I’m dropping Vizquel while he remains the subject of active litigation as well as an investigation by Major League Baseball. I still believe Vizquel’s on-field performance warrants induction. But he has five more years on the ballot, and I have no problem hitting pause on his candidacy when I consider 10 others deserving. Frankly, this is the course I should have taken all along.”

— Ken Rosenthal (The Athletic, 12/16/21)

“This is Vizquel’s fifth year on the ballot and the first time I have not voted for him. I have been a supporter of his candidacy because, unlike defensive metrics (that I typically don’t trust), I believe he was among the best defensive players to ever handle shortstop. I also believe, offensively, he was what teams wanted in a No. 2 hitter in the era he played… But in light of two ugly reports about his off-field conduct, that character check has switched spots on the ledger. I’m not the moral police. And I know the Hall isn’t filled with choir boys. But there are some offenses that shouldn’t be overlooked.”

— Dan Connolly (The Athletic, 12/28/21)

“In my eyes, Vizquel is one of the best defensive players in history and therefore deserves to be, at some point, in the Hall of Fame. Sadly, I don’t think that time should be next summer… As the father of six children, I do not take these allegations lightly or underestimate them down to a simple ‘they are things that happen in a dressing room.’ Especially if the potential victim is someone with autism. Hoping to have more clarity on the matter, I decided not to vote for Vizquel this year. I reserve the right to change my mind in the future.”

— Enrique Rojas (ESPN Deportes, 12/31/21)

Update for 2023 on Vizquel’s Troubles

On December 27, 2021, after most of the BBWAA writers had made up their minds, Omar Vizquel issued a statement on Twitter in which he declared that “the supposed domestic violence accusations put forth by my now ex-wife Blanca García were disregarded by the judge due to a lack of evidence or any supporting evidence,” adding that García “intentionally used my name and my persona in a defamatory manner but that her allegations were ultimately denied and dismissed.”

Hall of Fame historian Jay Jaffe, in his thoroughly researched piece about Vizquel and his issues, notes that “his statement appears to conflate activity in his divorce proceedings (mainly a matter of dividing up assets) with clearance of domestic abuse (while he was arrested in 2016 on a charge of fourth-degree assault, he was never prosecuted because she declined to testify.” Jaffe also noted that the divorce proceeding was ongoing, as of December 2022.

Regarding the sexual harassment allegation (that he exposed himself to an autistic batboy while managing the minor-league Birmingham Barons), the White Sox and Vizquel reached a confidential settlement with the batboy in June 2022.

Jaffe has many more details about Vizquel’s domestic abuse and sexual harassment cases at the end of his piece about Vizquel, and sums up his thoughts about Vizquel’s Cooperstown candidacy this way:

“While it does not necessarily follow that voters would or should directly connect allegations of domestic violence or sexual harassment against any candidate to the ‘integrity, sportsmanship, [and] character’ clause in the Hall of Fame’s voting instructions, it’s not out of bounds for a voter to do so, viewing such matters as far more serious than, say, PED violations. In that light, it’s understandable why voters might choose to withdraw their previous support, and/or to withhold it even after the cases have been closed. This is all dark stuff, and even for those of us who were prepared to squabble over the shortstop’s statistical qualifications for the remainder of his candidacy, nobody could have imagined his case would take this surreal and disheartening turn.”

— Jay Jaffe, FanGraphs (Dec. 22, 2022)

Conclusion

Omar Vizquel’s support from all of the voters who left his name off the ballot could, of course, return if he’s cleared of the allegations against him. I’m not a BBWAA member but, as someone who writes more about Hall of Fame candidates than all but a couple of them, I never felt that Vizquel was worthy of the Hall based on his performance on the field. In my view, you can’t have it both ways. You can’t say “this guy isn’t one of the 10 best players in the league,” virtually ever (the lack of MVP votes), and then say “he’s one of the top 1% of all players in the history of the game.” That is inconsistent.

Vizquel was a very good player and perhaps the most sure-handed shortstop in the history of the game. However, there is statistical evidence that his defensive prowess might be overrated and, with virtually no MVP votes in his entire career and no World Series titles, it’s hard to make a Hall of Fame case.

Having said that, I used to think it was a near certainty that Vizquel had a Cooperstown plaque in his future simply because history has shown us that players who cross the 50% vote barrier eventually get inducted, either via the BBWAA or the Veterans Committee. It’s quite possible, in the absence of the domestic violence and sexual harassment allegations, that Vizquel would have made it into the Hall of Fame this summer or in 2024. That’s not a certainty, of course. He might have run into a sabermetric “wall” of writers such as myself who didn’t believe his numbers matched the reputation.

Regardless, as long as Vizquel has the cloud of these allegations hanging over him, the point is moot. He’s not getting anywhere close to Cooperstown.

Thanks for reading. Please follow Cooperstown Cred at @cooperstowncred.

Embed from Getty Images

Source: https://t-tees.com

Category: HOW