The notion of a Universal Basic Income (UBI)—an unconditional minimum income, guaranteed for all without work, or means-testing—is enjoying a vogue. Progressives can support the concept in the name of economic justice. Techies can support it as social insurance against the great impending displacement of workers of which they warn. Even some libertarians can support it as an envisioned firewall against an otherwise expansive social welfare state.

With the COVID-induced economic crisis of 2020, the UBI took its first steps out of the ivory tower and into the world of policy. The CARES Act’s famous $600 a week Pandemic Unemployment Compensation benefit, available irrespective of employment or poverty status, albeit temporarily, was distinctly UBI-like. Similar provisions nevertheless remain in force: in December 2020, for example, roughly 10 million Americans were unemployed, but nearly twice that number were collecting government “unemployment” payments.

You are viewing: What Is A Nilf

To date, most of the debate about UBI has centered on its affordability—i.e., its staggering expense. But a scarcely less important question concerns the implications of such largesse for the recipients themselves and civil society. What would a guaranteed income mean for the quality of citizenship in our country, given that a UBI would allow some—perhaps many—adult beneficiaries to opt for a life that does not include gainful employment or other comparable work?

As it happens, an experiment of sorts is already underway to help us answer this very question. Thanks to the American Time Use Survey (ATUS) from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, we have detailed, self-reported information each year on how roughly 10,000 adult respondents spend their days—from the moment they wake until they sleep.1 These surveyed Americans include prime-age men who are not in labor force (or “NILF” to social scientists), ordinarily in their peak employment years, who are neither working nor looking for work. By examining the self-reported patterns of daily life of these grown men who do not have and are not seeking jobs, we may gain insights into the work-free existence that some UBI advocates hold to be a positive end in its own right.

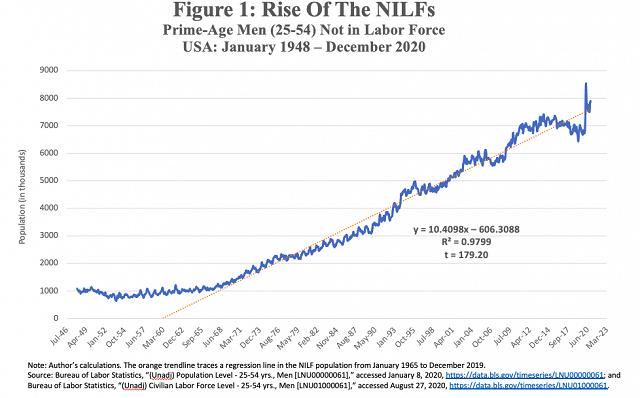

Even without a UBI, America has seen an extraordinary increase in the ranks of workless, prime-age men over the past two decades (see Figure 1). Although the number of prime-age NILF men held steady at roughly one million throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, that total has exploded since. Just before the pandemic hit, almost 7 million civilian, non-institutionalized men between the ages of 25 and 54 were out of the workforce altogether. For over half a century, the growth in America’s population of prime-age NILF men has been astonishingly steady and regular, rising by roughly 10,000 each month from 1965 to 2019.

Just how and why so many men in the prime of life should now be swept up in this flight from work is a matter of continuing scholarly research and debate. For now, it will suffice to observe that these many millions of men already draw on resources sufficient to afford a work-free existence.

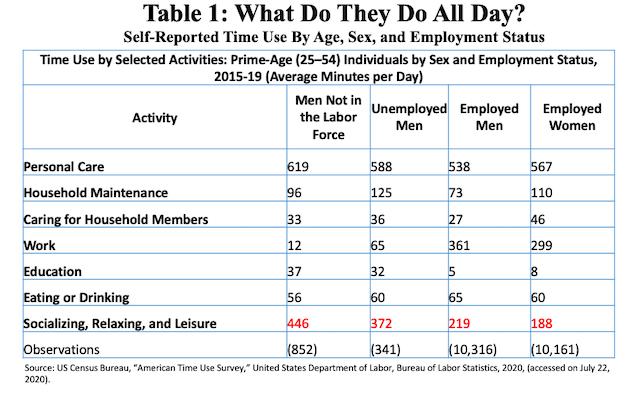

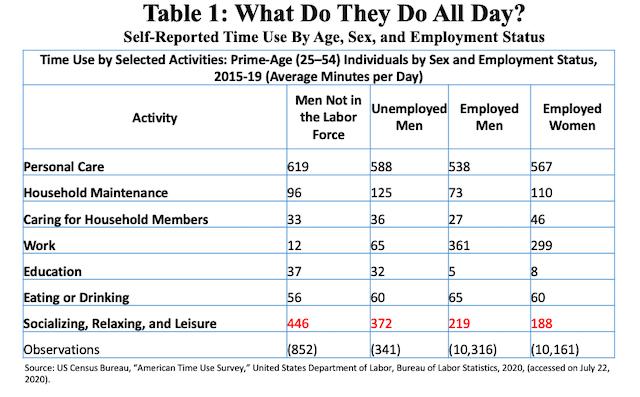

So what do these work-free men do with all their time? We can best answer that question by comparing their self-reported activities with those of other 25-54 year-old Americans surveyed by ATUS: employed men; unemployed men; and employed women. The “employed” men and women in this survey, incidentally, are not necessarily full-time workers—even men and women very slightly employed are counted in this category. The “unemployed,” for their part, are persons currently jobless who want work and still consider themselves part of the labor force.

Though imposing in absolute terms, prime-age NILF men account for less than 3% of pre-COVID America’s adult population, and thus for a small number of observations in any single ATUS survey. For this reason, we pooled the five most recent years of the survey—2015 through 2019—to glean statistically meaningful results from the differences in time use between the prime-age male NILFs and their working counterparts.

Major differences in time use patterns distinguish prime-age male NILFs from other men and women their age (see Table 1 below). It is not surprising that NILF men report much less paid work than their peers—an average of just 12 minutes per day, nearly six hours a day less than employed men, and almost five hours a day less than employed women, but also close to an hour a day less than unemployed men. Perhaps more surprisingly, their time freed from work is not repurposed into helping out around the home, such as doing housework, cooking, and other tasks of home maintenance. In fact, they devote significantly less time to such home chores than unemployed men—less, too, than women with jobs. NILF men also spend much less time helping to care for other household members than working women—less time, as well, than unemployed men.

Read more : What Percentage Of 5 Is 3

Apart from work, by far the biggest difference between the daily schedules of NILF men and everyone else comes in what the ATUS calls “socializing, relaxing, and leisure,” a category that encompasses a range of activities, from listening to music to visiting a museum to attending a party. On average, prime-age NILF men spend almost seven and a half hours a day in such diversions—over four hours a day more than working women, nearly four hours a day more than working men, and over an hour more than jobless men looking for work.

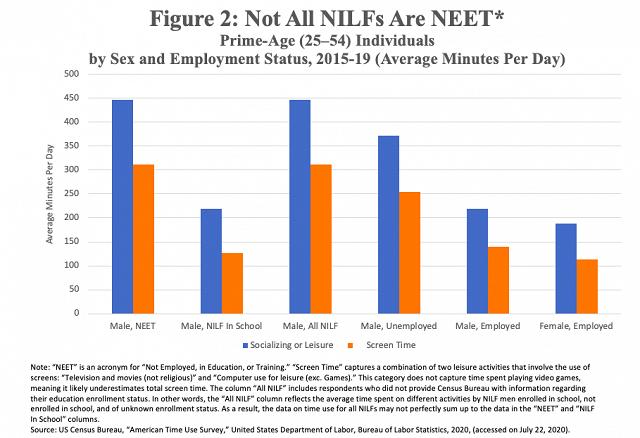

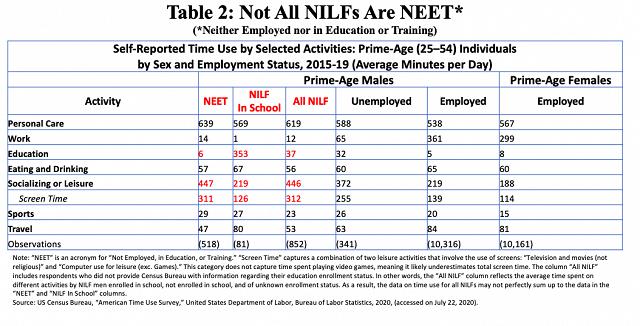

But NILF turns out to be a catch-all category that merges two very different populations. One of them is adult students, out of the labor force for training to improve their job prospects upon return. The other is a group British parlance calls “NEET”—an acronym for “neither employed nor in education or training.” The NEETs are in effect complete labor force dropouts. And in contemporary America, the overwhelming majority of prime-age male NILFs are NEETs: in the years 2015-19, according to Census Bureau data, fewer than one in six NILFs was an adult student. In the lead-up to the COVID pandemic, this meant one in 10 prime-age men was neither working, nor looking for work, nor seeking the skills that might help them return to the workforce.

If we disaggregate prime-age NILFs into NEETs and adult students, two strikingly different ways of life are revealed.

On the one hand, adult students reportedly spend an average of nearly six hours a day on their education or training—and since those averages include weekends and holidays, these men are committing over 2,100 hours a year to their schooling. The converse of such motivation is an unusually low involvement in “socializing, relaxing, and leisure”—distinctly less than for working men, though not as little as for prime-age working women, a notoriously “leisure-poor” population.

On the other hand, self-identified prime-age NEET men spend about seven and a half hours a day in “leisure activities.”2 That works out to about 2,700 hours a year—almost 1,600 hours a year more than working women, nearly 1,400 hours a year more than working men, and remarkably enough, over 450 hours a year more than unemployed men.

Economists and other social scientists often use “leisure” and “free time” interchangeably, but this is a mistake. The “leisure” activities that NILFs and NEETs indulge in are generally not the sort of higher pursuits that, for example, Josef Pieper had in mind in his classic Leisure: The Basis of Culture. The overwhelming majority of this “leisure” is screen time: television, internet, DVDs, and all the rest. NEET men reported an average of over five hours a day in front of screens—nearly 1,900 hours a year, almost equivalent to the time commitment of a full-time job. ATUS does not ask specifically about video games; if it did, even more NEET screen time commitment would almost certainly be recorded.

To go by the time-use surveys, prime-age men without work who are not looking for jobs and not engaged in training spend almost three times as many hours in front of screens as working women and well over twice as many as working men.3 Strikingly, they also report over 300 hours more screen time per year than their unemployed counterparts—men likewise jobless but who want to get back to work. And the reality is even more disturbing than these time-use numbers can convey on their own. According to a 2017 study by Alan Krueger, almost half of NILF men reported taking some form of pain medication every day. The fraction for NEET men would likely be higher still. The rhythms of life for a great many of the prime-age men in America currently disengaged with the world of work is defined not simply by days and nights sitting in front of screens—but sitting in front of screens while numbed or stoned.

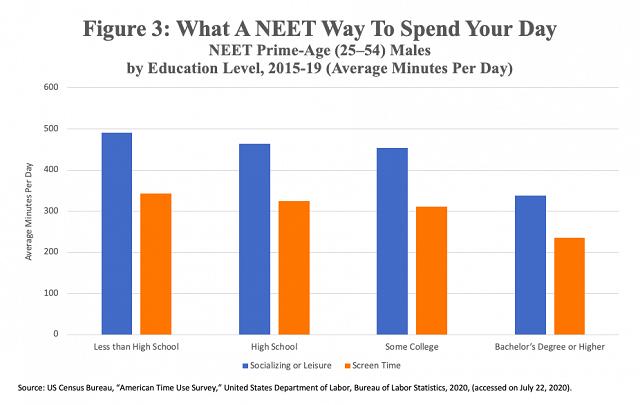

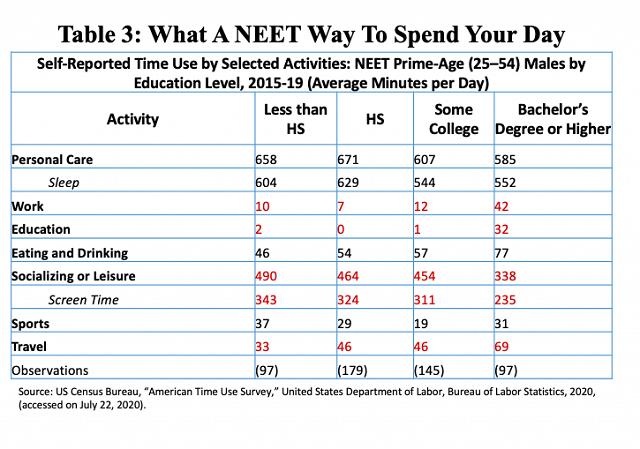

There is plenty of sociodemographic diversity within this enormous NEET contingent, and it casts light on differences in the daily routines of non-working men by education (see Figure 3 below and Table 3 in the Appendix). The lower their educational attainment, for example, the more NEET men tend to sleep (“personal care”) and to sit in front of screens, and the less time they spend out of the house on assorted rounds. Even so, workless male college graduates spend more time sleeping, eating, and drinking than working men and women, and far more time in front of screens—over twice as much as employed women, and nearly twice as much as men with any paid work.

The BLS has been releasing time-use surveys annually since 2003. Over that decade and a half, some of the most dispiriting tendencies in daily life for work-free men seem to have worsened. Screen time seems actually to have risen for NEET men from levels that were already anomalously high. Over this period, the reported gap in screen time between working and unworking prime-age men grew by nearly 300 hours a year—and that gap might look even larger if we had information on video game play.

Read more : What Is Editorial Modeling

The portrait of daily life that emerges from time-use surveys for grown men who are more or less entirely disconnected from the world of work is sobering. So far as can be divined statistically, their independence from obligations of the workforce does not translate into any obvious enhancement in their own quality of life or improvement in the well-being of others.

To go by the information they themselves report, quite the contrary seems to be true. Though they have nothing but time on their hands, they are not terribly involved in care for their home or for others in it. They are increasingly disinclined to embark on activities that take them outside the house. The central focus of their waking day is the television or computer screen, to which they commit as much time as many men and women devote to a full-time job. So far as we can tell, moreover, screen time is sucking up a still-increasing portion of their waking hours.

There would seem to be no shortage of anomie, alienation, or even despair in the daily lives of men entirely free from work in America today. Why, then, would we not expect a UBI—which would surely result in a detachment of more men from paid employment—to result in even more of the same?

Arguments can be made, of course, that UBI would attract a different sort of “unworking” man from those who predominate the prime-age male NEET population today. But the patterns we have presented on the daily routines of existing work-free men should make proponents of the UBI think long and hard. Instead of producing new community activists, composers, and philosophers, more paid worklessness in America might only further deplete our nation’s social capital at a time when good citizenship is already in painfully short supply.

Nicholas Eberstadt holds the Henry Wendt Chair in Political Economy at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) in Washington, DC. Evan Abramsky is a Research Associate at AEI.

1. Since ATUS covers the population 15 years of age and older, some of the respondents included are not legally adults; however the under/over 15 year demarcation comports with global demographic conventions, which classify those under 15 as children or young dependents and this 15-64 as the economically active age group.

2. In the ATUS surveys, many of the prime male NILFs not engaged in education or training do not specifically report this. In our study we present findings only for those NEETs who actually identify themselves as such. That omission, however, does not appear to affect results for prime age NEETs appreciably. We can be confident of this because there are no major discrepancies between results for self-reported NEETs on the one hand and the entire pool of NILFs with self-reported students subtracted from it and the other.

3. Prime-age male students who are out of the workforce spend even less time in front of screen than employed men and women—another sign of their focus and motivation.

Appendix (Tables)

Source: https://t-tees.com

Category: WHAT