The Missing Link

If you remember heading west on the Big Bend stretch of Interstate 10 in the 1980s, it would be nearly impossible to forget the rhythmic sound heard by every driver from Tallahassee to Pensacola: Ba-bump. Ba-bump. Ba-bump. A fitting soundtrack to play against 200 mind-numbing miles of green trees, grey pavement and straight, yellow lines.

In January 1966, that annoying soundtrack was little more than a song waiting to be written. But for Big Bend residents and businesses, announcements about the proposed location of Leon County’s sweep of I-10 had become like a broken record. Ten years had elapsed since former President Dwight Eisenhower had signed into law the legislation creating the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways. West of Tallahassee, the now-iconic 2.5-mile bridge over Escambia Bay was already open to traffic. Drivers to the east could take I-10 from Lake City to Jacksonville. But for East-West travelers wanting in, out or around the Capital City, Highway 90 was the best available option among the reliable, but slow, existing roads.

You are viewing: When Was I10 Built

Beyond inconvenience, Leon County drivers, residents and businesses were angry and embarrassed that their portion of I-10 — dubbed “The Missing Link”— was among the last sections of the cross-country highway to get underway. Over the years, as many as 14 routes north, south and through the center of Tallahassee had been selected for survey, repeatedly raising and dashing the expectations of area residents and businesses.

Between 1964 and 1965 alone, four possible I-10 paths were considered. These were narrowed to three after the Federal Bureau of Public Roads (then part of U.S. Department of Commerce) rejected a central route submitted by the Florida Department of Transportation (then the State Roads Department) that would have run parallel to the Seaboard Airline Railroad tracks, just below the Capitol complex. One of the three remaining routes would have run south of the city, following Orange Avenue in and out of Leon County. This route fell to arguments that the single access point it would provide Tallahassee would lead to traffic woes and cause travelers to bypass the city altogether. A northern path similar to today’s existing route would have entered Leon County south of U.S. 90 at the Jefferson County line and run northwest, near what today is Killearn Estates and through the southern portion of Lake Jackson before entering Gadsden County 4.5 miles above the city limits. But opposition to dividing Lake Jackson — as well as a well-heeled, nearby residential area — prevailed. A fourth route was needed.

In August 1965, the Tallahassee Chamber of Commerce proposed a northern route circumventing Lake Jackson and the adjacent upscale neighborhood, instead running through a nearby, less-developed area from which fewer families would have to relocate. City and county officials backed the plan, and the State Roads Department (SRD) followed with a decision to study the route. Tallahassee exhaled; it seemed The Missing Link finally had been found.

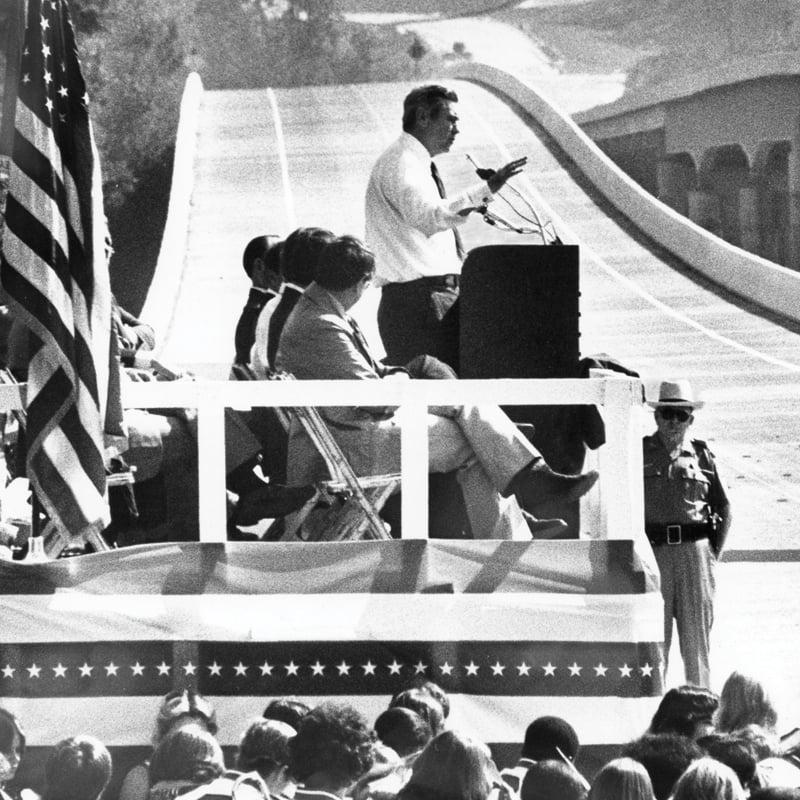

But relief was short-lived. In November 1965, the SRD unexpectedly came forward with new plans to route I-10 south of the Tallahassee city center as part of a proposal supported by then-Gov. Haydon Burns. While on the campaign trail through Northwest Florida in 1964, Burns had championed a southerly route running as near as possible to Panama City. His new proposal drew a bee-line from Live Oak, through Leon County and south of Blountstown to a small, unincorporated city of 200 called Ebro, 32 miles from Panama City and adjacent to Eglin Air Force Base. The SRD responded with an alternate route for I-10 that ran through northern Leon County, dipping sharply south at Blountstown to join Burns’ proposed bee-line in Washington County.

Again, the Big Bend’s hopes were dashed. In the wake of another possible eight to nine months of waiting for new survey results, the issue reached a fever pitch. Years of indecision had cost Tallahassee millions in lost industry and jobs in addition to citizens’ countless hours idling in traffic caused by city transportation infrastructure in need of advancement but also dependent on I-10’s unknown ultimate location for effectiveness.

By January 1966, a delegation of city and county officials and Chamber leaders had met in-person with Gov. Burns to underscore support for the previously agreed-upon northern route. By this time, local public concern centered less on where I-10 would be built and more on whether it would be built at all. Though the southern route would be less expensive than its preferred northern counterpart, every day spent considering it exposed Florida to a more costly risk: States were required to have all interstate highways approved, in construction or built by 1972 to qualify for federal funding, which would cover a whopping 90 percent of the cost of building the roads.

Read more : When Is Jensen Ackles Birthday

In the weeks and months following, news reports identified possible causes for the last-minute change. One involved a connection between State Road Board Chairman Floyd Bowen and the Washington County Kennel Club, for which incorporation papers listed Bowen’s brother-in-law, A.J. Dunn, as vice president. The financially embattled dog track was located in Ebro, the westernmost point on Burns’ bee-line before the road turned north toward Defuniak Springs. Other reports pointed out the potential for an easy state purchase of the Leon County property along Burns’ route. Nearly all of it was owned by the St. Joe Paper Company, part of the Alfred DuPont Estate and managed by Wakulla Springs owner Edward Ball, negating the need to obtain right-of-way from multiple, smaller landowners.

But the bee-line had a hitch: As drawn, it would have to traverse Eglin Air Force Base. Since the early 1960s, Eglin officials had quietly and consistently refused to accommodate any road that would divide the base or force relocation of its vital functions. Eglin also refused the northern Leon County option that dipped sharply southwest at Blountstown to join the bee-line, citing dangers posed to drivers by close-by, “heavily used bombing and gunnery areas.”

Over the 1965 holiday season, progress on a decision had ground to a halt. The Big Bend was exasperated nearly to the point of indifference. In a January 1966 editorial, Tallahassee Democrat Editor Malcolm Johnson captured local sentiment: “All we in Tallahassee want is a fixed route.”

Via a March 8 letter to Gov. Burns from the U.S. Department of Commerce, the Big Bend got what it wanted. Burns’ request to defer I-10 development for another study was denied, and the decision to construct the road as planned along North Leon County would stick. Within days of settling the highway’s location, in-city wheels of advancement began to turn. With an I-10 route established, City Planner Phillip Pitts announced Tallahassee’s plans to proceed with its major downtown thoroughfare, designed to increase access to downtown Tallahassee, accommodate an influx of students at Florida State University and Florida Agricultural & Mechanical University, and group downtown streets in one-way pairs to reduce traffic congestion and confusion.

Though a small number of local citizens expressed discontent with the location of the road, most of the capital city’s general population had abandoned ideals in favor of filling in the Missing Link as expeditiously as possible. By 1970 the gap was fading into history, and ground for I-10, largely as it exists today, had been broken. I-10 opened to traffic between Pensacola and Lake City in 1978.

Remembrances of Using an Unfinished Highway for Youthful Adventures

Now often referred to as a dull drive, I-10 once was a wonderland for local children.

Rob Vickers, a senior program manager at CDM Smith (formerly Wilber Smith, which recommended an early I-10 route through the city center) lived on his parents’ tract of land, which directly abuts the I-10 corridor. Vickers was 8 years old when construction began.

Read more : When Is Jake Paul’s Fight

“I was a kid, so I didn’t see a massive infrastructure project happening 200 yards from my house,” Vickers said. “I saw a source of fun.”

For Vickers and his siblings, “fun” included exploring the nearby underground cavern created by a “borrow pit” developed by engineers as a source of soil needed at other construction points. As is common in low-lying areas, the borrow pit began to collect groundwater. Vickers remembers water entering the cavern looking “like waterfalls.” After I-10 had been paved, but was not yet open for traffic, it served Vickers’ siblings as a great place for bike riding. Vickers’ father sometimes used the empty stretch for high-speed driving to “blow out the carburetor,” on his 1971 Chrysler Newport.

And then, there were the Caterpillars. Caterpillar Earth Movers, that is, parked by the developer on the Vickers’ property. When nobody was watching, Vickers and his siblings often climbed the dirt-hauling vehicles. One day, Vickers’ brother, Mitch, mustered up the gumption to crank one.

“We couldn’t turn it off,” Vickers said with a chuckle. “Had it been put in gear, it would have mowed down part of a subdivision directly ahead.” Fortunately, the group was discreetly rescued by Vickers’ uncle, whom he describes as “a mechanic who could keep a secret.”

Things that Went Bump on I-10

I-10’s most famous construction wrinkle was heard and felt but never seen. For several years after I-10 opened from Tallahassee to Pensacola, drivers unknowingly helped the elements compose the pulsing thump beneath their tires as they drove the 200-mile stretch. By the 1980s, complaints began to rival the bumping itself. Less than 10 years after I-10 opened to the public, the state began construction to address design flaws leading to the tiresome sound.

“I-10’s original slabs were made of Portland Cement Concrete laid directly onto an aggregate base on top of clay soil, and were not tied together with reinforcing steel known as dowel pins,” said now-retired, 31-year DOT construction training engineer Gordon Burleson. Also, he explained, the clay soil’s impermeability enabled it to trap water under the pavement. “The weight of passing cars, combined with a soft base caused the slabs to tilt and make a bumping sound as cars moved from slab to slab,” he said.

Several methods were used to correct the problem. In some areas, dowel pins were placed in the joint area between slabs and the tilted joints were milled (ground) smooth. In other areas the original Portland Cement Concrete was removed altogether, crushed at a rock crushing plant and used as an aggregate for asphaltic concrete. Another method was to completely crack the concrete slabs transversely every two to three feet and apply a “crack relief layer” of liquid asphalt with rock laid on top, followed by another layer of asphalt and smaller rock with the final layer being an asphaltic concrete riding surface.

Source: https://t-tees.com

Category: WHEN