Moody, methodical and measured, “Road to Perdition” takes a brooding look at the wages of sin and the heritage of violence among hoodlums during the dark days of Prohibition. Predominantly concerned about the passing of nasty traditions from fathers to sons, and the strenuous effort of one killer to be redeemed through his boy, Sam Mendes’ much-anticipated second effort after his Oscar-winning “American Beauty” finds him working in a very different key while displaying an even more pronounced attentiveness to tone, genre variations and artistic niceties. Absorbing drama sees Tom Hanks fitting comfortably into the role of a morally aware bad guy, and while history has shown that one should never underestimate Hanks’ extraordinary B.O. draw, production’s autumnal feel and A-plus awards-season pedigree will make it fascinating to see if DreamWorks can pull off its gamble of putting this over as a summer attraction that can successfully duke it out with the more obvious popcorn pictures. Its seriousness notwithstanding, crime drama looks to play well with all audiences, although appeal to women could be somewhat limited.

“Sons are put on this earth to trouble their fathers,” Illinois mob boss John Rooney (Paul Newman) confides to his top enforcer and surrogate son, Michael Sullivan (Hanks), a remark that has deep significance for both men and frames the concerns of the movie. Rooney, now an old man, has seen his biological son, Connor (Daniel Craig), go hopelessly astray into reckless (as opposed to “respectable”) criminality, while Sullivan still hopes he can somehow keep his two pre-teen boys from inheriting his bloody legacy, having kept the nature of his work a secret for as long as possible.

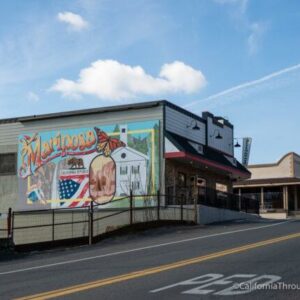

You are viewing: Where Was Road To Perdition Filmed

It’s a potent theme, one that recalls not only “The Godfather,” with which “Perdition” shares “family” concerns, a dark look and period detailing, but also such explosive father-son dramas as “East of Eden.” The connections to Coppola and Kazan are telling in the precision performances, resonant settings and perhaps above all in the unhurried pacing; while crisply edited and unindulgent, Mendes’ work is gratifyingly old-school in its rejection of modern-day stylistic agitation, the better to achieve a slow but inexorable build to its climax.

That said, the film’s heart still rests in the realm of pulp fiction, in this instance a 1998 graphic novel penned by Max Allan Collins (who wrote 15 years’ worth of the “Dick Tracy” comic strip in addition to the historical Nathaniel Heller thrillers) and illustrated by Richard Piers Rayner. David Self’s adaptation retains the 300-page tome’s basic structure and principal characters while elaborating many scenes and tamping down its sensationalism.

One thing the film doesn’t clarify at the outset is its setting, which might seem to be a suburb of Chicago but is actually Rock Island, Ill., clear across the state on the Mississippi River. Irish mob kingpin Rooney (changed from the character’s real-life inspiration, John Looney) is presiding over the wake for the wayward son of a longtime foot soldier (Ciaran Hinds), and when the latter gets out of hand by (rightly) accusing Rooney of his son’s killing, Sullivan effectively intervenes.

Read more : Where The Forest Meets The Stars Summary

But when Rooney later tells Connor and Sullivan to pay the bereaved father a visit on a rainy night, Connor overdoes things as usual by shooting him, an effort quickly joined by Sullivan, who machine guns some other goons. Unbeknownst to them, Sullivan’s 12-year-old son Michael Jr. (Tyler Hoechlin) has observed the whole thing, and the disturbed father receives his son’s assurances that he’ll never mention what he saw to a soul.

But Connor isn’t so sure and, egged on by the knowledge that his father has always much preferred Sullivan to him — a fact vividly conveyed after a tense mob board meeting by a great shot of Rooney walking away, his arm around Sullivan, with the ignored Connor in the foreground — Connor goes to Sullivan’s house to snuff the potential squealer when he knows the man’s away, but kills the wrong son, the younger favorite Peter (Liam Aiken), as well as Sullivan’s wife (Jennifer Jason Leigh).

As with most of the considerable violence in the film, the murders are handled obliquely by placing them offscreen, the aftermath dealt with in understated fashion. For his part, Rooney is furious at Connor, beating him and cursing the day he was born, while the two remaining Sullivans get out of town, knowing it’s too dangerous to stick around even to bury their loved ones.

At the 45-minute point, they hit Chicago, beautifully evoked on modern La Salle Street with a modest amount of digital erasures to convey 1931. Sullivan offers to go to work for Al Capone’s (real-life) right-hand man, Frank Nitti (Stanley Tucci), for whom he has done jobs in the past. But Nitti’s ties to the Rooneys prove more binding, resulting in the Italian’s recruitment of gimpy freelance hitman (and professional crime-scene photographer) Maguire (Jude Law) to do Sullivan in.

Film’s second half, then, consists largely of a slow cat-and-mouse chase, with Maguire pursuing his prey across the flat Midwestern rural landscapes while Sullivan tries to stay one step ahead, break through to the son to whom he’s never been close and even get the upper hand on the Capone gang. The latter he achieves through the ingenious ruse of robbing small-town banks where the Chicagoans have deposited “dirty” money, a sequence of events wonderfully and concisely expressed in a fluid montage of lateral left-to-right tracking shots intermingled with Maguire calmly rolling a quarter through his filthy fingers.

Read more : Where To Buy Deadstock Fabric

In one very fine scene, Maguire catches up to Sullivan in a lonely roadside diner, where they exchange some cryptic remarks before the inevitable fireworks. Significantly less satisfying is a crucial encounter Sullivan has with a mob accountant (Dylan Baker) who inexplicably is running around the boondocks with incriminating financial documents in hand. After Sullivan manages to exact the rain-soaked revenge he has so patiently sought, climax and coda fulfill the promise of fateful inevitability while providing the right measure of final dramatic release.

Practically every effect in the movie has been calibrated to the nth degree, from the nuances of the family dynamics and the color coordination of the decor to more subtle details such as laying a coffin on ice to keep the body cold but also to link with the winter snow outside, to emphasize the frigid ossification of the mobsters’ lethal behavior patterns. But the picture is able to deflect charges of preciousness by putting narrative and character first; it’s suffused in a distinct sense of aestheticism, but not artiness.

Of all the film’s accomplished creative contributions, certainly the most notable is Conrad Hall’s extraordinary cinematography. Whereas “American Beauty” was distinguished by its vibrant coloration, “Road to Perdition” is characterized by seemingly infinite shadings of brown, with strokes of black and green but little real color. Pic is filled with soft shadows, and backgrounds that tend to vanish in obscurity. As in “Beauty,” lensing has been intricately coordinated with other primary craft efforts, particularly the deeply evocative production design of Dennis Gassner, Albert Wolsky’s fabric-heavy cold-weather costumes and the superbly chosen Chicago-area locations. Thomas Newman’s inventive score, while appropriately serious toward the end, seems intent upon lightening the mood earlier on with some overly busy and cutesy orchestrations and melodic doodlings.

Playing his first outright bad man, albeit one with commendable traits of loyalty and filial responsibility, Hanks happily resists any temptation to soften his character or quietly suggest to the audience that he’s really an OK guy under it all; Sullivan is tough, clammed up and not easily expressive even to his son, who is compellingly underplayed by Hoechlin. His late-career vocal rasp scarcely in evidence, Newman is in excellent form as the mob boss with a stranglehold on his medium-sized town, and his intimate scenes with Hanks possess a lovely great-star-to-great-star quality, without ostentation. His hair thinned and his body bent at odd angles, Law makes a memorably creepy assassin, a sort of Weegee willing to kill to create his artistic subjects. Carefully selected supporting cast is spot-on.

With “Gangs of New York” yet to come, this looks like the year of the Irish-American gangster.

Source: https://t-tees.com

Category: WHERE