CCSS-M G-CO 5: Given a geometric figure and a rotation, reflection, or translation, draw the transformed figure using, e.g., graph paper, tracing paper, or geometry software. Specify a sequence of transformations that will carry a given figure onto another.

You are viewing: Which Transformation Will Always Map A Parallelogram Onto Itself

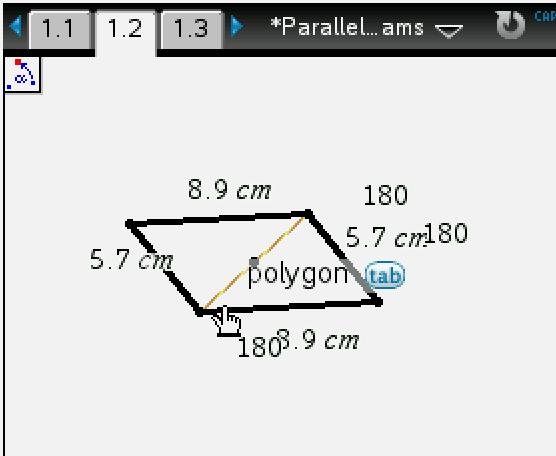

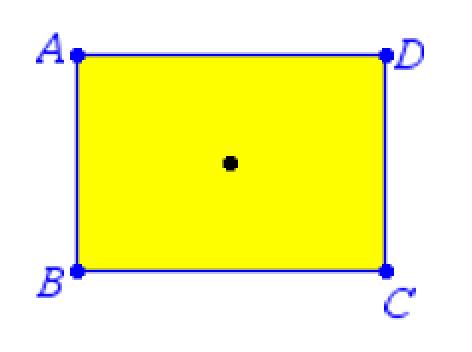

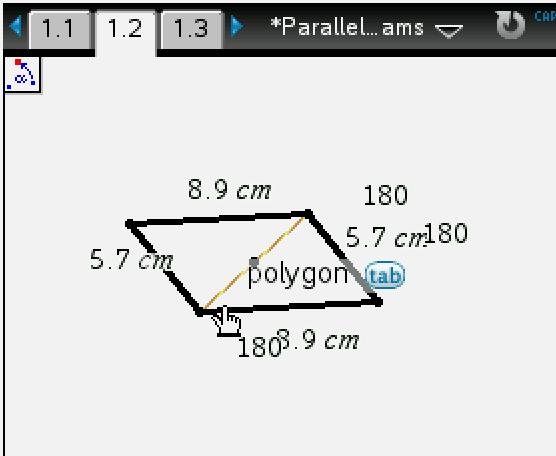

We define a parallelogram as a trapezoid with both pairs of opposite sides parallel. Students constructed a parallelogram based on this definition, and then two teams explored the angles, two teams explored the sides, and two teams explored the diagonals. I monitored while they worked.

We discussed their results and measurements for the angles and sides, and then proved the results and measurements (mostly through congruent triangles).

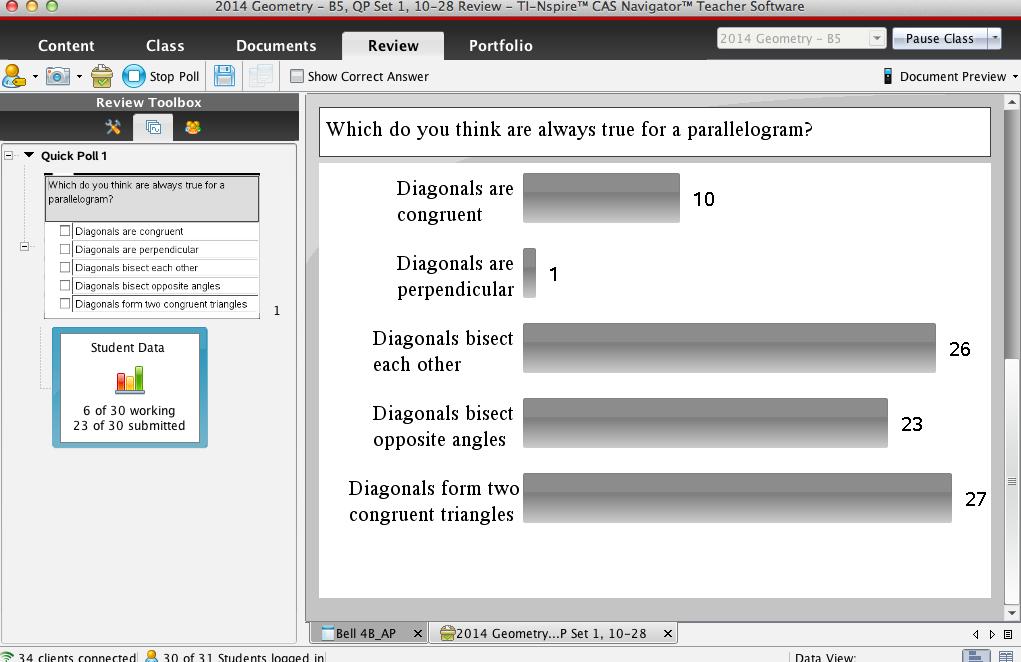

I asked what they predicted about the diagonals of the parallelogram before we heard from those teams.

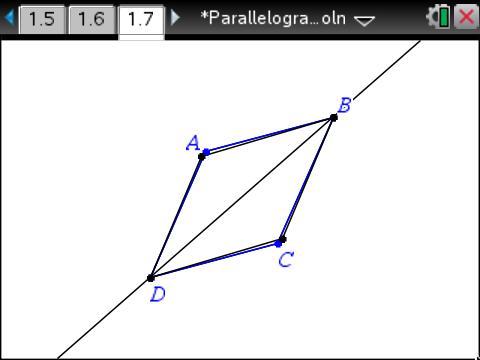

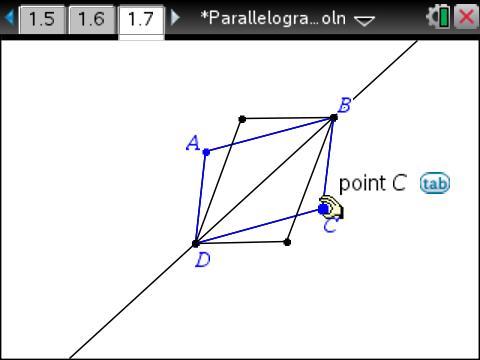

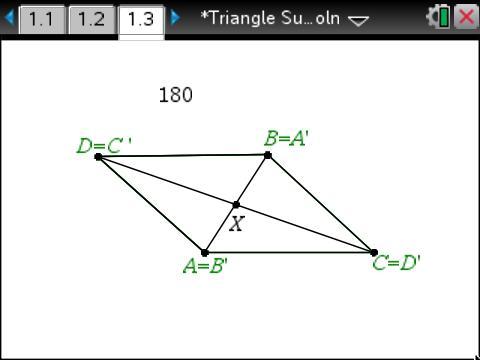

We saw an interesting diagram from SJ. She explained that she had reflected the parallelogram about the segment that joined midpoints of one pair of opposite sides, which didn’t carry the parallelogram onto itself.

So how many ways can you carry a parallelogram onto itself?

Or can you?

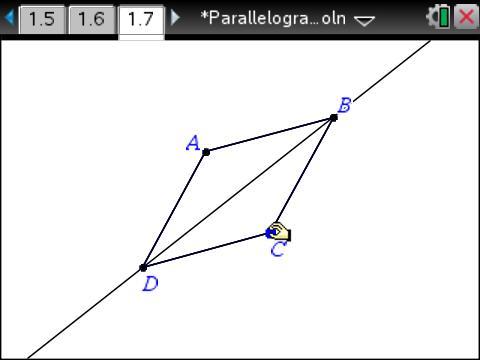

What if you reflect the parallelogram about one of its diagonals?

It doesn’t always work for a parallelogram, as seen from the images above. But we can also tell that it sometimes works. For what type of special parallelogram does reflecting about a diagonal always carry the figure onto itself?

Read more : Which Liens Are Correctly Identified As General Or Specific

It’s obvious to most of my students that we can rotate a rectangle 180˚ about the point of intersection of its diagonals to map the rectangle onto itself.

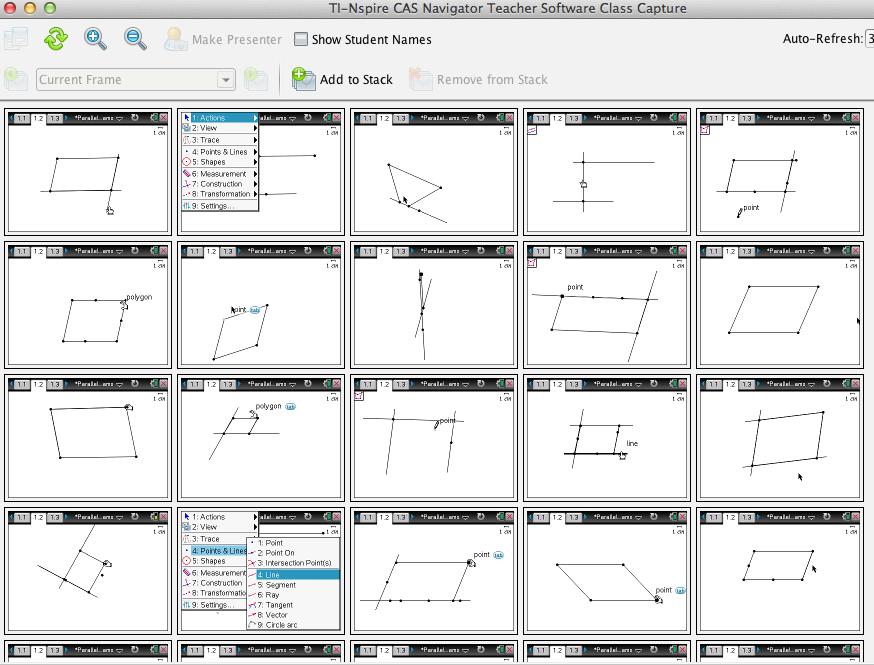

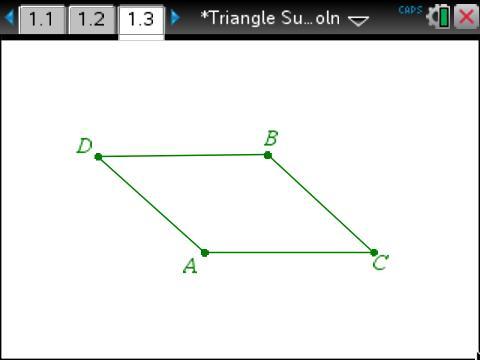

It’s not as obvious whether that will work for a parallelogram. We need help seeing whether it will work.

One of the Standards for Mathematical Practice is to look for and make use of structure.

Drawing an auxiliary line helps us to see.

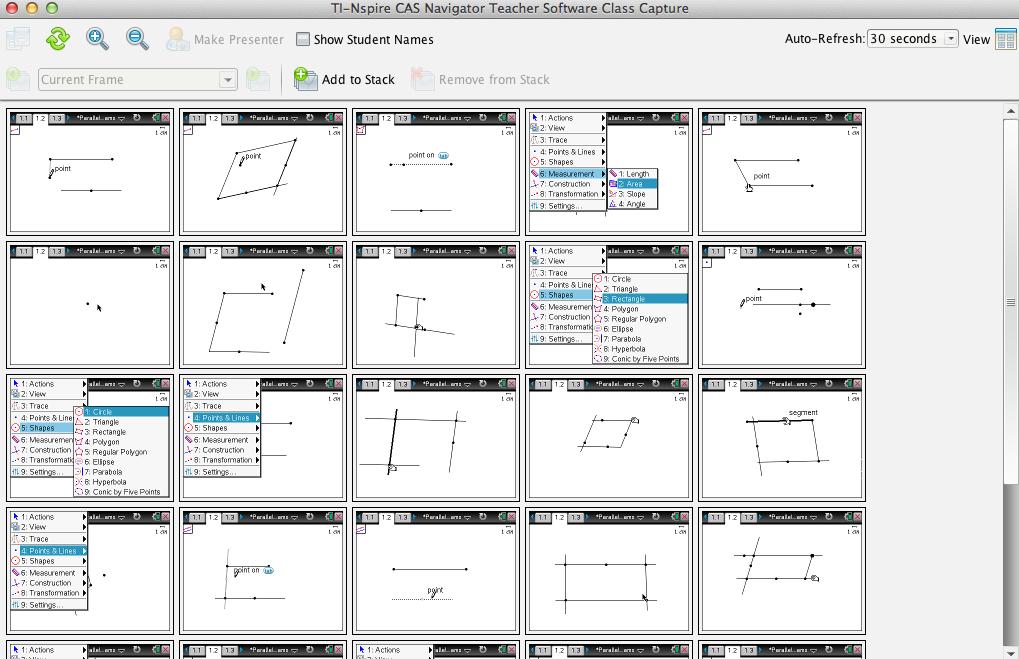

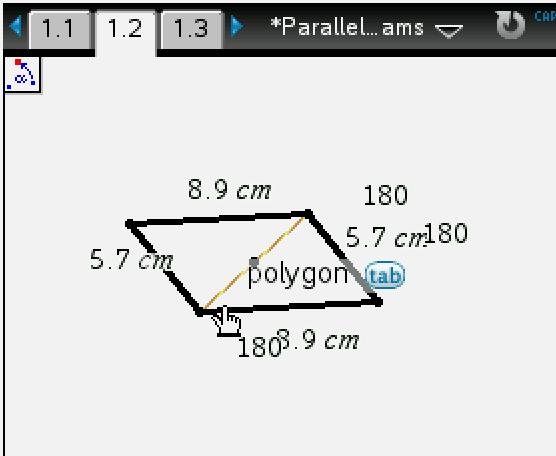

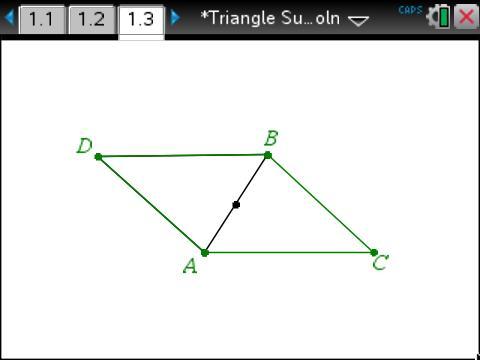

The diagonals of a parallelogram bisect each other. Since X is the midpoint of segment AB, rotating ADBC about X will map A to B and B to A.

Since X is the midpoint of segment CD, rotating ADBC about X will map C to D and D to C.

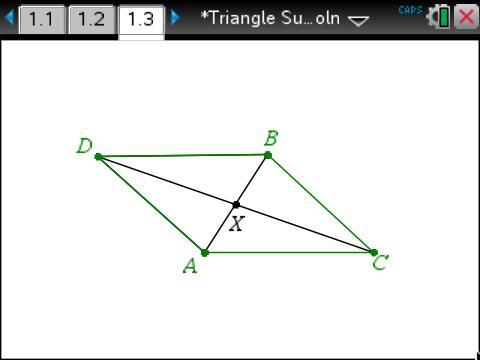

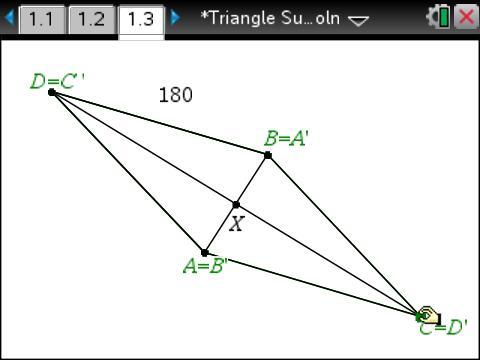

We can verify with technology what we think we’ve made sense of mathematically using the properties of a rotation.

The change in color after performing the rotation verifies my result.

The dynamic ability of the technology helps us verify our result for more than one parallelogram.

Read more : Which Hotels Let You Check In At 18

Is rotating the parallelogram 180˚ about the midpoint of its diagonals the only way to carry the parallelogram onto itself?

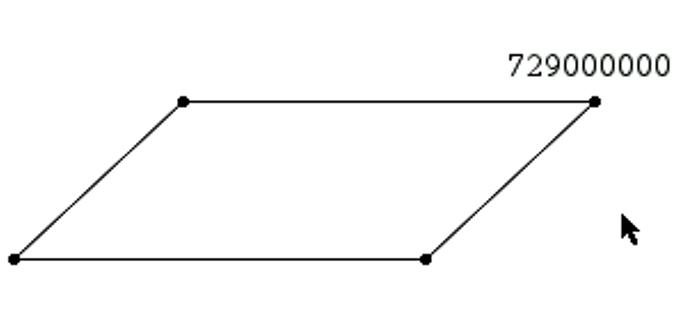

Before I could remind my students to give everyone a little time to think, the team in the back waved their hands madly. 729,000,000˚ works!

Did you try 729 million degrees? Why does it work?

And yes, of course, they tried it. Because they can.

And they even understand that it works because 729 million is a multiple of 180. (I’ll even assume that SD generated 729 million as a multiple of 180 instead of just randomly trying it.)

We did eventually get back to the properties of the diagonals that are always true for a parallelogram, as we could see there were a few misconceptions from the QP with the student conjectures: the diagonals aren’t always congruent, and the diagonals don’t always bisect opposite angles.

@jgough tells a story about delivering PD on using technology to deepen student understanding of mathematics to a room full of educators years ago. A college professor in the room was unconvinced that any student should need technology to help her understand mathematics.

Jill looked at the professor and said, “Sir, I need you to remove your glasses for the rest of our session.”

He looked up, “Excuse me?”

Jill answered, “I need you to remove your glasses.”

He replied, “I can’t see without my glasses.”

Jill said, “You have a piece of technology (glasses) that others in the room don’t have. You need to remove your glasses.”

The college professor answered, “But others in the room don’t need glasses to see. I do.”

Jill’s point had been made. As the teacher of mathematics, I might not need dynamic action technology to see the mathematics unfold. But we all have students sitting in our classrooms who need help seeing.

What opportunities are you giving your students to enhance their mathematical vision and deepen their understanding of mathematics?

Source: https://t-tees.com

Category: WHICH