Does the removal of a tyrant remove tyranny? This question is worth having a stab at, especially in terms of understanding how political performances are used to engage an audience. Caesar’s epic assassination, which has inspired and foreshadowed so many acts of liberators against tyranny, has many insights to offer, both as an historic event and as a political performance. In a modern world of Twitter and Instagram, images and acts often supercede words, going “viral” to a broad audience in a matter of hours. In the ancient world, however, a broader audience could only be reached during large public events, and afterwards by word of mouth or subsequent accounts. This meant that actions and, particularly, performances played a profound role in shaping public consensus. It was not only what people said, which could always be subject to manipulation, but how people behaved, that affected the public perception of an event. Modern neuroscience has recently proven what leaders like Caesar already knew: people don’t follow or recall words as clearly or as quickly as they interpret imagery.

Performance culture is so effective in ancient and modern contexts because it is an act that engages all the senses. Spoken words engage the ears, written words engage the eyes. But a performance appeals to numerous sensory receptors simultaneously. The more senses employed to corroborate an account, the more credible it seems, and the more likely it is to survive as a memory. In order to understand political life and the surviving literary accounts, one has to consider how experiencing public events can shape a narrative, not only in terms of what a person sees but also in what he/she remembers. Neither perception nor memory are perfect. How one feels about an event can fundamentally impact both of these processes. Part of reconstructing an historic event is reconstructing the experience: the stage, the characters, the actions (the performance) and the reactions (the audience’s response).

You are viewing: A Guard Who Tears Decorations From Caesar’s Statues

Caesar’s assassination is an excellent case study for experiencing history. Surviving historic accounts by Suetonius, Plutarch and Cassius Dio paint a vivid picture of events before and after Caesar’s murder. This imagery has been used by subsequent authors, such as William Shakespeare, to recreate a dramatic performance of history, that has been the subject of reinterpretation for hundreds of years. The assassination of Julius Caesar represents both a moment of political transition from republic to monarchy as well as one of life’s most difficult quandaries: is murder ever justified?

Although ancient accounts reflect different perspectives and agenda, perhaps the most interesting aspect of Caesar’s assassination, as it is recorded through three different characters in Plutarch’s Lives (Antony, Brutus, and Caesar) and interpreted in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, is the absence of a hero or a villain in the tale. Rather than offering a judgment, this episode offers a demonstration of how political culture operated in ancient Rome and particularly, how politicians used performances and public media to convey a message. The victor, not necessarily the hero, is the man who manipulates the crowd.

Did Caesar want to be king?

“Uneasy lies the head that wears the crown” –Shakespeare, Henry IV Part II, Act 3 scene 1

The prevailing question for many historians is whether or not Caesar wanted to be a king. The fact that most ancient sources were written afterwards, when the Emperor Augustus and his successors were indeed trying to establish a monarchy, imposed considerable restraints (more detailed study here). Claims of kingship, had a profoundly negative reception in Rome, kings were expelled, and people accused of behaving in a kingly manner (e.g. Tiberius Gracchus) were cudgelled to death on the steps of the Capitol. For someone as politically savvy as Caesar, moves towards outright kingship would have been a very risky manoeuvre. More likely, Caesar was beginning to behave like a bit of a “diva”: not a god or a king but someone who expects preferential/ “royal” treatment. He did hold an unprecedented concentration of political power, especially after being awarded the title “dictator for life” by the Senate, for which he seemed to expect a degree of preferential treatment. A few key events are cited by Roman historians as illustrations of Caesar’s increasingly majestic airs: his triumphal return to Rome (Autumn of 45 BC), the “statue incident” (ca. early 44 BC), and his behaviour at the Lupercalia festival (mid February 44 BC). *The exact chronology of the last two events is not clear: timing switches between Suetonius and Plutarch.

Caesar’s Triumphant Return to Rome:

Plutarch’s account of Caesar’s return to Rome presents the Roman audience as the crown bearers for Caesar: “…the Romans bowed their heads before Caesar’s good fortune and accepted the bridle”. The triumphal procession, in which a successful general returned on a chariot in purple robes bearing a crown of victory, likely derived from Etruscan traditions, did present a victor in a royal manner. However, this was an established ritual for victors in Roman culture. Caesar’s subsequent behavior towards those who had fought against him (Brutus & Cassius) was merciful, as was his treatment of Pompey, his deceased adversary, whose fallen statues he restored (Caesar 57). Caesar’s refusal to take on a personal guard (the hallmark of a tyrant) was also exceptional: “he refused personal guards, instead he wore his popularity, which he regarded as his best and reliable protective talisman….”. Shakespeare’s play begins with members of the crowd (a carpenter and a cobbler) in awe of Caesar’s triumph, for which they have been given a holiday (something guaranteed to win public approval).

After his election as “dictator for life” (dictator perpetuo) by the senate, concerns arose regarding Caesar’s role: “…when permanence is added to the unaccountability to the autocracy, tyranny is the result.” (Plutarch Caesar 57) There was a public incident where two men had dressed Caesar’s statues with filleted laurel wreathes (the sign of a King). The tribunes Epidius Marullus and Caesetius Flavus, who appear in the opening lines of Shakespeare’s play, shoo these men away (they were arrested according to Plutarch & Suetonius) and remove decorations from the statues. Caesar’s reaction, taking the tribunes to the senate and having them stripped of their office, was probably a bit heavy handed. While Caesar claimed that he had wanted a chance to refute the claims himself, many believed that his actions reflected his growing pride and arrogance. From this point onwards, Plutarch and Suetonius cast Caesar as a man with royal aspirations. It is probably worth differentiating between behaving like a “diva” and believing that one should be king. When called “King” by the crowd Caesar responded clearly “I am Caesar, not Rex” (Plutarch, Caesar, 60-61, Suetonius Julius 79, Cassius Dio 44.10 and Appian’s Civil Wars 2. 16. 108). The opportunity to publicly refute claims of kingship to a broader audience was clearly something that Caesar desired.

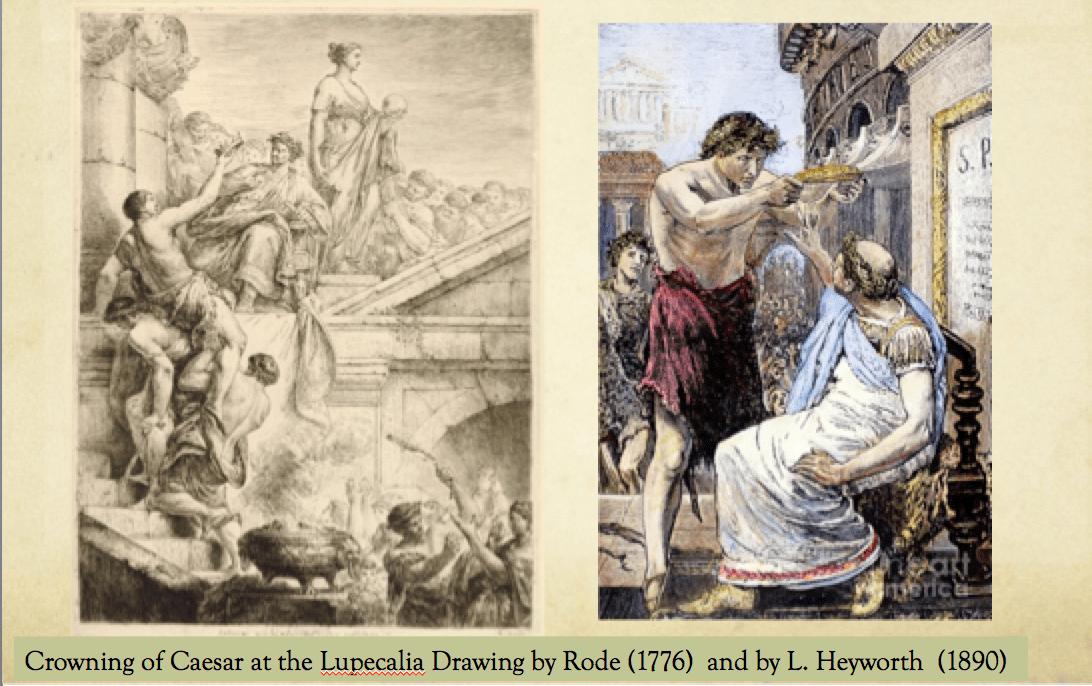

Caesar at the Lupercalia: Whipping up popular support

Caesar’s behaviour at the Lupercalia, one month before his assassination, is often presented as key point of agitation for his assassins (Suetonius Julius 79 and Plutarch Antony 13). The Lupercalia ( See my blog entry ) was a raucous festival of role reversals, where young aristocrats (including Mark Antony) were oiled up and ran about in their pants with a piece of goatskin, playfully whipping matrons for fertility. It is important to understand this context: the Lupercalia was a popular festival with a large public audience and a relaxed and jovial atmosphere. Any political message conveyed in this context was likely to be light hearted:

“They (the Luperci) run about in sport and strike at anyone they meet. Antony was one of these runnners but instead of carrying out the traditional ceremony. He twined a wreath of laurel around a diadem and ran with it to the rostra… placing the diadem on Caesar’s head, implying by this gesture that he deserved to be made king, At this Caesar made a show of declining the crown, whereupon the people were delighted and clapped their hands… this pantomime continued…. the crowd greeted every refusal with shouts of applause”: Plutarch Antony 12 trans. I. Scott-Kilvert (Penguin edition) 281-282.

In Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, Caesar playfully entreats Mark Antony to remember to whip his wife Calpurnia, to which Antony replies “I shall remember. When Caesar says ‘do this’ it is performed.” This is a clear reference to performance that the two have scripted for the day, which Plutarch described as a “pantomime”. The Greek is διαμαχομένων “a struggle or fight” but the playful context and the fact that one of them was mostly naked presented a comic altercation with a clear message: people might want to crown Caesar but Caesar did not want to be crowned. Casca, one of the chief conspirators, reports the event as “mere foolery” in Shakespeare’s version.

While Plutarch considers the ulterior motives that may have been at work, he also notes a crucial dichotomy in the audience: though they are willing to be ruled by a kingly figure, they unanimously reject the title. Caesar seems to have understood this, as did his successor Octavian (later the emperor Augustus), who made a show of turning down honorary titles offered by senate. The need to juxtapose and differentiate Augustus from his predecessor may also explain why Caesar is presented in in later accounts with such a lust for power and kingship. The idea that Caesar, who was widely viewed, even by a disapproving Cicero, as a savvy spin doctor, chose to ignore his audience’s innate hatred of kings, is hard to accept. At the Lupercalia, in a merry context before a large audience, one could see Caesar’s performance (almost certainly pre-planned) as a light hearted attempt to diffuse a potential public relations disaster. Rather than casting Caesar as a king, his role at the Lupercalia more likely represents an attempt be viewed as one of Rome’s founders, like Romulus and Remus: For a more detailed analysis the event see J. North’s compelling article.

Beware the Ideas of March! Caesar’s Assassination

Read more : Who Is Pablo Lyle Wife

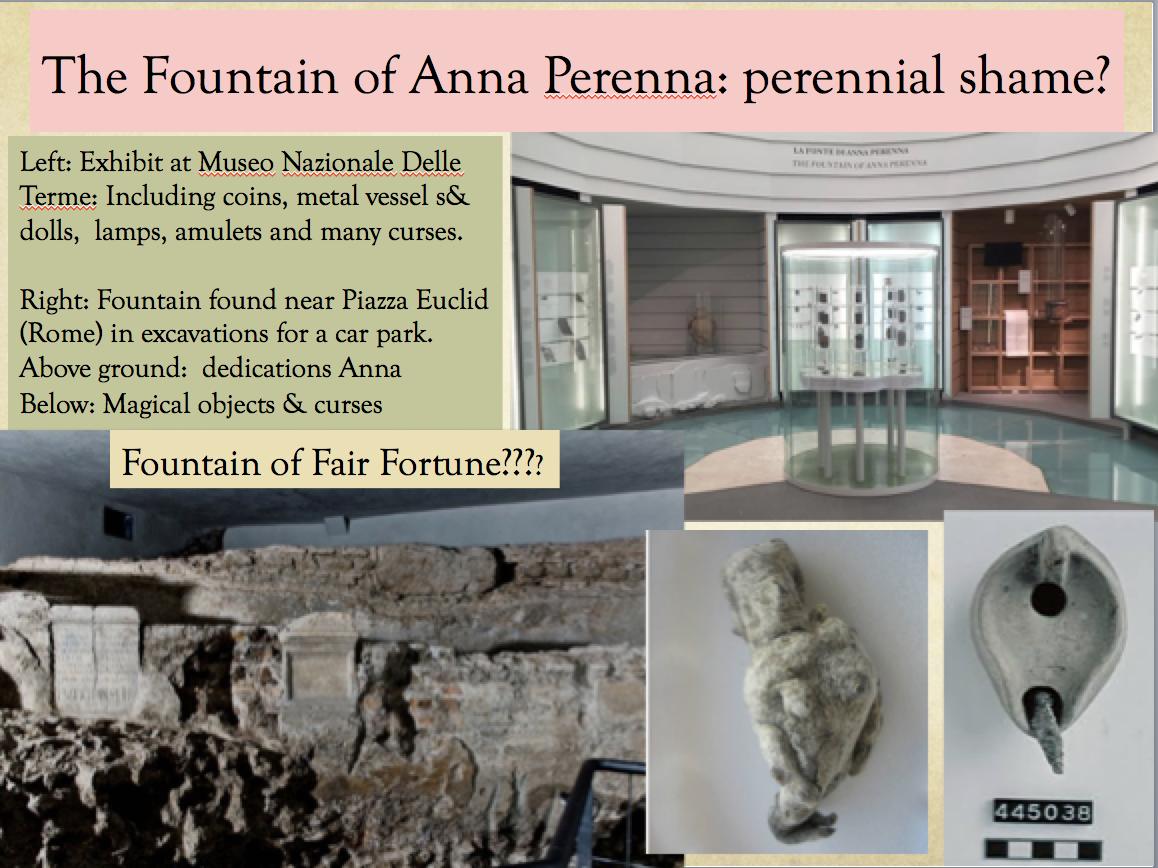

The Ides of March (March 15th), the feast day of Anna Perenna, whose name “to live (and last) throughout the years” refers to the perennial turning of years (in the old Lunar calendar, it referred to the first full moon). The festival of Anna Perenna, according to Ovid (Fasti 3.523-696.) took place in her sacred grove outside the city, by the first milestone of the Via Flaminia. Young Roman couples stayed up, camped out in the trees, drank together and …. it was probably not dissimilar to modern festivals with songs, mimes and dancing, literally and figuratively “letting their hair down” (e.g. Woodstock, Glastonbury).

The people come and drink there, scattered on the grass,

And every man reclines there with his girl.

Some tolerate the open sky, a few pitch tents,

And some make leafy huts out of branches….

..But they’re warmed by sun and wine, and pray

For as many years as cups, as many as they drink.

to celebrate the perennial changing of the seasons.

Ovid Fasti 3. Trans. Online A. Kline

But it was not all song and dance. Despite Ovid’s raucous accounts her festival, the recent discovery of a fountain for Anna Perenna off the Via Flaminia in Rome in 1999 (photo) revealed numerous curses (including amulets, lamps containing metal tablets and dolls with nails struck through them) Marina Piranomonte’s article of magical finds from the fountain. These objects, beautifully studied and displayed the Museo Nazionale Epigrafico in Rome (Link), attest to a darker more vengeful side of perennial sentiments. The beginning of one cycle and the end of another, the Ides of March was the perfect context for both a political transition between republic and empire, as well as the thin line between love and hate.

Caesar’s assassination was not a “public” event: it took place in the Curia Hall of Pompey’s theatre, in the shadow of Caesar’s former adversary: Pompey. Accounts of how Caesar died, how he delayed attending the meeting, how the plot was nearly foiled, add to the dramatic quality to the event as well as the sense of ensuing chaos. Suetonius records how Caesar fought the first blow, stabbing Casca with his stylus, but when he saw all the men, he covered his face and hiding his legs (Julius 82). Suetonius acknowledges other accounts, where Caesar spoke to Brutus in Greek : καὶ σύ τέκνον “And you my child”. While it is unlikely that a dying man, recently stabbed in the throat, spoke (in Greek?), Caesar’s final comment hangs like a ghost in the air. It acknowledges the depth of Brutus’ betrayal and foreshadows Plutarch’s account of how Brutus was haunted by Caesar’s ghost.

“he fell on the ground on the pedestal on which the statue of Pompey stood: and the pedestal was so drenched with blood from the murder that it seemed as though Pompey himself had presided over the punishment of his enemy, who lay on the ground jerking convulsively from his many wounds…in an revealing outcome, a number of conspirators accidentally wounded each other in the process.” (Plutarch Caesar 66; Brutus 17).

Caesar’s assassination was not a public event, but outcome was still chaotic: Caesar fell at the foot of Pompey but no one steps up to fill the void. The senators rushed outside and fled in confusion, an act which appeared to the public as panicked rather than triumphant. The Roman people fled home and locked their doors (Plutarch Caesar, Suetonius, Julius 82), a PR outcome that would have left Caesar turning in his grave. The “liberators” were so focused on the assassination they did not take the time to plan or coordinate the practical consequences: how to spin Caesar’s murder in their favour.

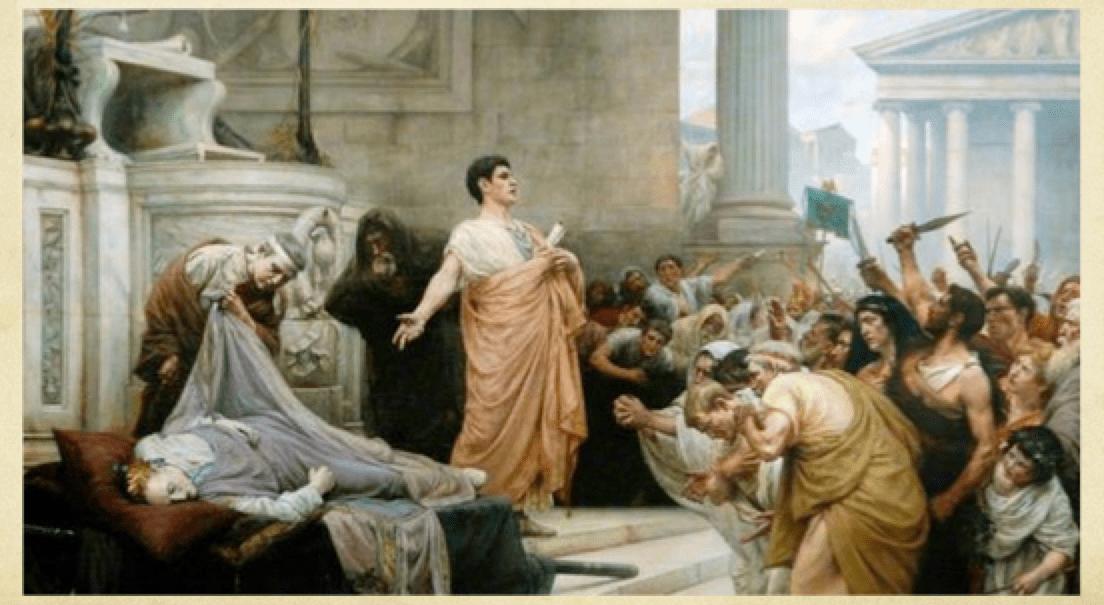

The Funeral: Inflaming the Public

“Stike me down and I shall become more powerful than you can possibly imagine” –Obi Wan Kenobi

The lack of planning by the conspirators became clear in the days that followed. The same men who betrayed their pacts of forgiveness with Caesar, entered naively into a truce with Mark Antony. To legally justify their actions, the liberators needed to declare all actions of Caesar null and void. However, the clementia (mercy) these men had betrayed came back to bite them as Senators realized that offices, promotions and the settlements for Caesar’s army would also be nullified. Brutus’ arguments to save Mark Antony’s life and his approval of Antony’s request for funerary oration were acts of great virtue, but they would eventually result in Brutus’ death. While senators tarried, Marc Antony got hold of Caesar’s will, which (supposedly) contained a settlement of 3 gold pieces for every Roman citizen.

While Shakespeare’s play made compromises in historical accuracy and timing, the speeches of Brutus and Antony are brilliant reflections of character, and in particular, their ability to sway popular opinion. Brutus’ words are straightfoward and connect his actions with virtues.

Read more : Who Makes A Split Cal King Mattress

As Caesar loved me, I weep for him;

as he was fortunate, I rejoice at it; as he wasvaliant, I honour him: but, as he was ambitious, Islew him. There is tears for his love; joy for hisfortune; honour for his valour; and death for hisambition.

The crowd replies positively “live Brutus live!” then they suggest that he be Caesar: “Caesar’s better parts shall be crown’d in Brutus”. This popular response highlights Plutarch’s claims: the Roman people didn’t want a liberator, they wanted a Caesar. Brutus’ attempts to depose Caesar have only created a void for Brutus to fill.

Reacting to the popular response, Mark Antony offers a more compelling impression of Caesar. Although his speech was recreated for dramatic effect by Shakespeare, it follows the sentiment of Plutarch’s account, in which Antony “casts a spell over the people” by his words and sways them with a performance (Plutarch Brutus 20, Antony 13, Suetonius Julius 84). Antony’s speech is the antithesis of earnest values and virtues presented by Brutus. His words stand in contradiction to his actions and the performance he presents, complete with props (a will, tears and a bloody robe).

Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears;I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him

Antony asks the Romans for their ears, but he appeals to their senses. And of course, he is there to praise Caesar. Rather than citing intangible virtues, Antony relies upon public consciousness and memory: Caesar’s victory processions and the money he brought, his tears for the poor, Caesar’s refusal of the crown at the Lupercal. Were these acts ambitious? By accessing existing memories of public events, Antony provides a more persuasive proof. His audience is swayed by what they can see, touch, hear, and remember. The opinion of the crowd shifts, as one observes the grief in his tone, the redness of his weeping eyes.

Having gained both the ears and the emotive sympathy of his audience, Antony presses his advantage: setting out the terms of Caesar’s will, which (supposedly) promised each citizen three gold pieces. Finally, he picks up Caesar’s bloody robe. After two days, the sight, the smell of Caesar’s body and the robe must have been wretched but truly gripping imagery. So inflamed were the people that they ran for wooden benches and tables and began a pyre (Plutarch Antony 13, Brutus 20; Suetonius Julius 85). Afterwards with torches, they threatened the homes of Cassius and Brutus.

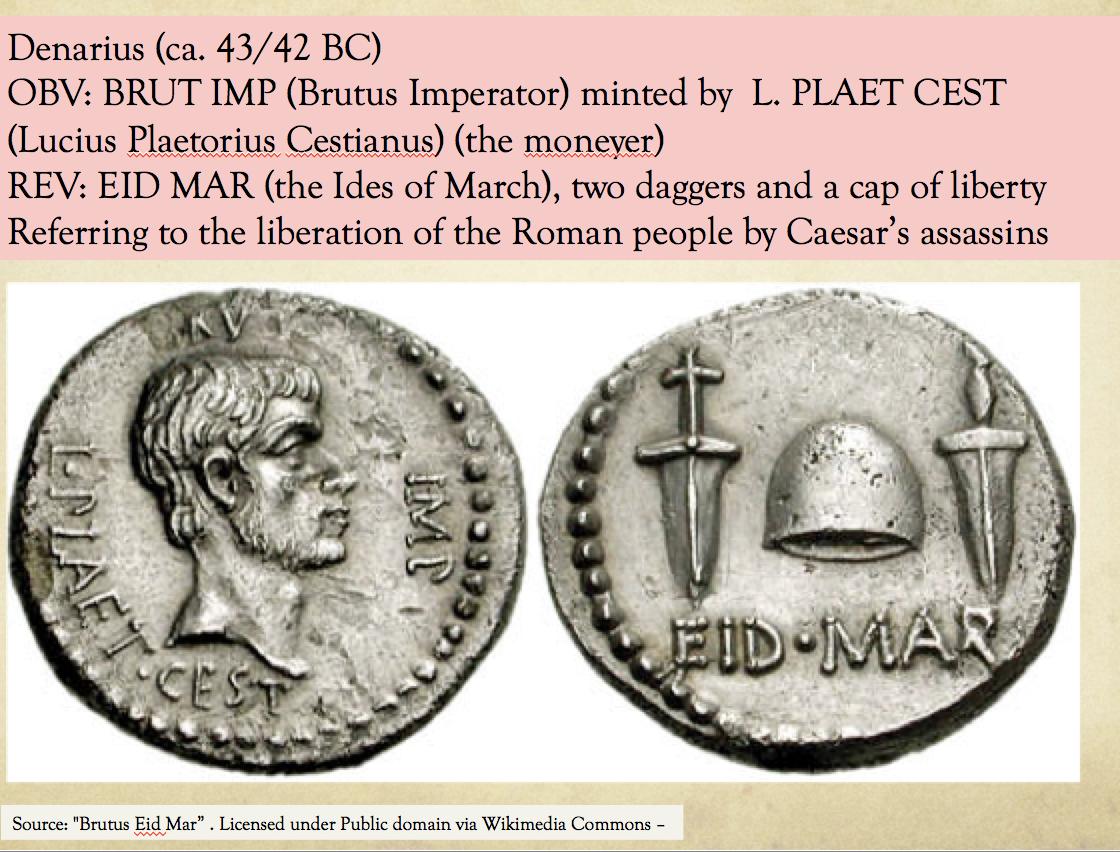

Liberty or Death: Visual Media & the Roman Legacy of Ides of March

The assassination of Caesar was not a success for the liberators. Brutus may have wanted liberty for the Roman people, but did his audience understand this aim? The aim of the liberators was to free the Roman Republic. However, as advocates of a constitutional government, the liberators actions defied its most fundamental tenet: murdering a Roman citizen without of proper trial. If one has to operate outside of a system of laws in in order to support them; then what it the merit or values of these laws. The only person with the legal power to take a citizen’s life in Rome was a Dictator. However Caesar might have behaved, his wielded this particular power with far more care than his opponents, leaning towards clemency, rather than death.

How does one legitimise an illegitimate act? The coins (a few gold (aurei) but mostly silver (denarii) minted by the liberators were designed to convey solidarity and positive imagery for the assassination to a broader audience. They present Brutus’ portrait and name and the title “Imperator” and image of two daggers and a cap with the insignia “EID MAR”. The reference to the calendar and a day of “turning the years” implied turning point for the Roman people towards liberty. However, the existence of only two daggers (for Brutus and Cassius?) does not present the murder as a collective act. Brutus’ use of his own portrait on the coin, discussed by Cassius Dio (47.25) was a potentially confusing contradiction: if putting his face on coins had made Caesar a tyrant, how were Brutus coins different? Replacing Caesar’s portrait with his own cast Brutus in a similar role: as Caesar’s replacement. Attempts to equate or juxtapose Brutus with Caesar were also unflattering: Caesar was a legally appointed ruler whose actions had been formally legitimised by the senate, Brutus’ role and his actions as a “liberator” were not (though they were pardoned).

The legacy of the Ides of March lived on. Octavian, whose legitimacy was defined, at least initially, by his relationship to Caesar, made an ostensible show of loyalty. He called himself “Caesar” and continued building projects in Rome (including a temple to Mars the Avenger). He commemorated the Ides of March in 40 BC with the sacrifice of 300 prisoners of war from the siege of Perusia on the Altar of Divine Julius in Rome (Suet. Aug. 15, Dio 48.14.2). There is a public performance with a very clear message. In addition to avenging Caesar’s death, the triumvirs (Mark Antony, Octavian and Lepidus) and the emperor Augustus sought to reinscribe history in the written accounts of the assassination and in Rome’s urban space. Pompey’s Curia Hall was converted to public latrines and the statue of Pompey was moved to the stage. The arrival of Halley’s comet after Caesar’s assassination was seen as a symbol of deification for Caesar, shifting focus away from his death even further.

Reception : Sic Semper Tyrannis “Thus always to tyrants”- words shouted by John Wilkes Booth after shooting Abraham Lincoln, attributed to Brutus.

Of all the political assassinations in the history of world, why has Caesar remained such a prominent model across history? Greg Woolf‘s book “Et tu Brute” is an excellent attempt to examine this phenomenon across the Roman world and beyond. The legacy of assassination haunted the majority of Roman emperors, whether plots were successful or not (they often were). The accessibility and the popularity of Plutarch’s Parallel lives, whose engaging, enlightening, and often moralising accounts of Rome’s most honourable men, inspired Christian audiences (particularly monks making copies of illuminated manuscripts). As questions of political power and monarchy arose in the Renaissance, Caesar presented a captivating figure.

Printing presses and a rise in multi-lingual translations increased the audience of readers. Shakespeare used Thomas North’s 1577 translation of Plutarch for his historic plays. Plutarch’s Parallel lives were an inspiration for a number of America’s founding fathers, including Benjamin Franklin and Alexander Hamilton. Shakespeare’s play has carried a legacy of its own with each new generation re-interpreting history through the lens of the present. John Wilkes Booth, the assassinator of Abraham Lincoln, appeared in at the Winter Garden in New York City in a version of Julius Caesar (as Antony). Orson Welles 1937 production viewed Caesar (who was idealised by Mussolini) through costumes in Fascist and Nazi styles.

Recent American productions of the play have cast Julius Caesar as a presidential figures including John F. Kennedy, Hilary Clinton, Barack, Obama, and recently in New York Public theatre (June 2017): Donald Trump. While there were some protests, reviewers sought to place the performance in context: this historic episode/play does not advocate assassination, rather, it reveals its perils of political violence (Photo). A recent production (2018) by the Bridge Theatre in London, which placed the audience within the stage, portrayed this in a captivating dramatic performance, where the audience could truly experience a version of history.

How do we understand history? politics? propaganda? How do we separate performance from reality? Each of us is a member of a media audience, which has expanded in recent times from being physically present at an event to being global viewers of visual and social media. Part of navigating this increasing media labyrinth is understanding our role as an audience. How are emotions and opinions can be manipulated by what we see, hear and experience. Perhaps the most brilliant aspect of Caesar’s assassination and Shakespeare’s play is the image of history it presents: an event with no villains or heroes but a world where virtues, vices, friendship, honour and patriotism clash, tearing at the fabric of society. It feels remarkably like the present.

What lessons can we learn for Caesar’s assassination? Forgiveness has a price. Violence often results in more violence. Ideological actions without practical considerations (e.g. an exit strategy) can be disastrous. Our eyes, ears and memories, may not be as reliable as we think. These are life’s perennial struggles as the years turn, they are what the Ides of March and the feast of Anna Perenna prompt us to remember: it is through the lens of past that we come to understand our role in the present, both as an audience and as a performer.

Source: https://t-tees.com

Category: WHO