![Nathan Benderson, a developer since the end of WW II, stands inside what will be a Target store off University Parkway near Interstate 75. [HERALD-TRIBUNE STAFF ARCHIVE / 2006 / DAN WAGNER]](https://t-tees.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/who-is-nathan-benderson.jpg)

This biography of the founder of the Benderson Development Co. appeared in the Herald-Tribune in 2007. Nathan Benderson died April 7, 2012, at the age of 94.

By age 15, Nathan Benderson was making more money than his father.

You are viewing: Who Is Nathan Benderson

Three years into the Great Depression, Benderson’s father, Isaac, had a broken spirit and was afraid to take a risk after making a decision that cost his family their home.

His son was not afraid of anything. He still is not.

Now 90 years old, Nathan Benderson’s development company, with more than 8,000 employees, is a national commercial real estate powerhouse. Benderson helped create one of the first outlet malls and was one of the first developers to venture into suburbia. Benderson Development Co. owns or manages 250 properties, a portfolio that includes 30 million square feet of office buildings, industrial parks, residential communities and hotels.

Among his holdings is a project that promises to upend Southwest Florida retailing: a 1 million-square-foot “lifestyle center” on the Manatee-Sarasota county line. The open-air mall, the first of its kind in the region, has landed high-end retailers Neiman Marcus and Nordstrom.

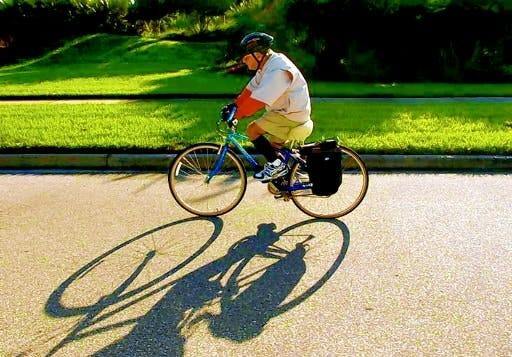

But Benderson, who moved his headquarters to Manatee County nearly four years ago, does nothing to trumpet that scope. Though he likely would make the Forbes 400 list of the world’s richest people, he lives in a relatively modest house in Manatee County’s University Park and likes to bike to work. The man who collected broken glass as a child to afford a new pair of shoes prefers to keep his fortune closely guarded and in the family.

“We’re not interested in being Donald Trump-type business people,” Benderson said. “That’s just an ego trip as far as I’m concerned.”

Starting young

Nathan Benderson began making business deals even as his father Isaac withdrew from that world.

As an elementary school student, the son walked up and down the front of his grandfather’s Buffalo, N.Y., cigar store selling Christmas tinsel. He sold fireworks for Fourth of July. He collected glass shards for his father to recycle.

Isaac Benderson was strict, never giving Nathan the 10-cent admission to Saturday matinees, so Nathan walked a mile to the Utica Avenue theaters, picking up pennies from tin cans at newspaper stands along the way.

He counted them first “to figure out how many I could steal,” he said. “If there were only four or five, I’d take one or two. If there was eight or nine, I maybe took two or three.”

As a teenager, Benderson figured out that he could make more buying and selling bottles from breweries than recycling glass. By 16, he quit school and bought an old truck, hauling bottles to as far away as Cleveland.

His father’s career was going in the other direction. When Benderson was 12, his mother came home one day to say she had sold the stock she had inherited from her parents. His father convinced her to buy back everything. A week later, the 1929 stock market crash occurred. The family lost its home.

By the time his father recovered, Benderson had given his parents the down payment for a new home, bought his own factory and was making “Old Favorite” root beer under his Niagara Dry Beverages label.

Bottles and a brewery

In 1939, soda was a seasonal business. To keep his plant going, Benderson slept in his car outside the plant in the spring and summer. Still, he was barely making it financially. When the weather cooled and demand dropped, the bill collectors arrived.

He took a trip to Florida, telling a friend who stayed at the plant it was OK to tell creditors exactly where he was. “They were so happy to think that I could afford to be in Florida. He didn’t have any trouble that whole winter,” Benderson said.

But in 1941, just as business started to pay off, Benderson was drafted. He left the factory in his friend’s care, shipping off to Bermuda, where he and others in the Army monitored shipping channels for German U-boats.

Within a year, the factory was losing money and Benderson could not pay his lenders. He took leave, came home and sold everything.

During the war, Benderson was sent to Mississippi, a “dry” state. Many fellow soldiers wanted something harder than base-served beer. Benderson made regular trips to Louisiana to slake the troops’ thirst for liquor. The business meant more money to send home for his wife, Dora, and their first son, Ronny.

After returning to Buffalo, Benderson’s father-in-law convinced him to come to work for him, making $100 a week. It lasted only three weeks. Benderson got back into bottles for five years, then decided to buy a brewery – trucks, equipment, beer, bottles, cases and all – at a foreclosure auction.

Read more : Who Wears The Oregon Duck Mascot Uniform

The bankers balked when Benderson handed over only $10,000 of a $275,000 bid, but he convinced them to let him take over the mortgage.

“I think in two years or so, they had all their money as I promised,” said Benderson, “and we owned the property.”

Building buildings

It was the brewery that made Benderson a real estate developer. He demolished the brewery’s tallest building to rent parking spaces to retailers nearby. Soon the gas company asked him to build an office. Then Metropolitan Life asked for space above the gas company.

“We had never built a building in our lives,” Benderson says.

Met Life was pleased enough that it ordered another dozen buildings during the next few years, trusting Benderson to get them done.

“That helped us get a start,” he said.

Early on, he struggled to get loans from Buffalo banks. Because no one in Buffalo knew where he got his money, there were rumors that Benderson had mob ties. Benderson blames the talk on anti-Semitism. The rumors kept him out of the Montefiore Club, an exclusive Jewish club, after he refused to sign an affidavit saying his money was not mob-related.

“More people thought we were going to go broke than thought we would become successful,” Benderson said. “We used to pay good interest.”

Today, of course, Benderson is part of Buffalo’s establishment. His involvement in projects “adds credibility and confidence,” said former Buffalo Mayor Anthony Masiello.

“The Bendersons don’t fool around. When they decide to do something, they do it. And they do it faster and better than anyone else,” Masiello said.

Bad deals

Like most developers, some of Benderson’s deals went sour. He lost $1 million lending money to a company working on a highway project. Once, he was sued after the wall of one of his buildings collapsed into another, killing an office worker. His construction company was found at fault.

In the 1960s, Benderson bought a downtown Buffalo office building and decided to convert it into condos. When the project failed, he lost $1 million.

After that loss, Randy Benderson remembered seeing his father cry for the first time. But he was back at work the next day, looking for another real estate development.

“We’ve never made a bad deal,” Nathan Benderson likes to joke. “Some just turned bad.”

Secret of his success

Jordan Levy, now a venture capitalist, recalls that Benderson was a favorite in their middle-class neighborhood.

Every evening, Benderson gathered Randy and his friends for an ice cream trip. They never went to the same place, so they got to sample most of what the Buffalo suburbs had to offer. What they did not know is that the trips were never about the ice cream. Benderson was driving around Buffalo scouting new sites for shopping centers and inspecting his developed properties.

“He had us all fooled,” Levy said.

Nathan Benderson is famous for his work ethic and his questions, the way he drills down into every detail of a deal – whether it is business or philanthropy. He expects those he deals with to have done their homework.

Ruth Kahn Stovroff, 93, remembers asking Benderson for a donation to build a hospice center in Buffalo. Her husband had grown up with him and their fathers were friends, but Stovroff was not prepared for Benderson the businessman.

When she walked into his offices, she was stunned at the extent of his holdings. Just as stunning was the way he questioned Stovroff about Hospice.

Read more : Who Are The Walter E Smithe Ladies

“He asked the most probing questions, some of which we couldn’t answer,” Stovroff said. “I was ashamed because you don’t go to Nate with just a request, ‘Hey, write a check.’ He gives so intelligently because he has to find out everything about the agency or the organization to which he gives.”

A year later, Benderson called Stovroff to set up a $250,000 endowment for Hospice.

‘Remarkable’ mind

Business associates all note Benderson’s ability to figure a deal in his head.

“He’s remarkable,” said Wayne Wisbaum, an attorney whose family has had a long association with Benderson. “He knows every tenant, every lease, the terms, the rents and he knows the vacancy rates at each of his shopping centers.”

Benderson poohs-poohs that talk: “Everything is hard work and common sense. If you don’t have common sense, you don’t have anything.”

Hard work to Benderson has always meant long hours. At age 90, there are still days when he is up at dawn and working late into the night. He never leaves the house before he exercises. He swims daily.

He expects the same work ethic from employees. Those who do not like the hours or expectations leave, but many have stuck with Benderson for decades, some in multiple generations.

Benderson is also famous for his frugality. He still picks up pennies and searches chairs and cushions for loose change. He would rather walk a few blocks than feed a parking meter. He does not eat in restaurants that do not offer free refills on iced tea and coffee.

For years Benderson drove beat-up cars. Today he drives Fords – although in Sarasota he sometimes pulls out a Rolls-Royce that his children bought him for his 80th birthday, a gift he tried to return.

The Benderson children knew their father was a hard worker and somewhat successful.

His oldest son, Ronny, who now runs Delta Sonic, a chain of car washes that offers rust-proofing, oil changes and gourmet meals, remembers the bottle business. He also remembers learning early on to turn off the lights and to always count his change.

Benderson said the lessons were intentional: He never wanted his kids to “get spoiled.” At restaurants he would not allow them to order Coca-Cola.

“I’d tell them, I’m not paying 75 or 80 cents in a restaurant,” he said. “On the way home, I’ll stop and get you a bottle of Coke for a nickel.”

To this day, Ronny meets his father at restaurants carrying a bottle of Coke and a bottle of Perrier, “and sits there smiling, just to aggravate me,” Benderson says.

Staying private

Three grandsons work for Benderson Development. One of them, Shaun Benderson, is an executive in the Florida operations. Benderson would not consider taking the company public.

Being independent has meant that he could pursue projects others thought were too risky.

His company is in the midst of two right now: a waterfront project in Buffalo and the University Town Center Mall on the Sarasota-Manatee county line.

For University Town Center, Benderson never had his doubts – even though the project is beyond his usual retail project.

Benderson said it used to make him sick to think that someone was going to buy the land before he could.

Skeptics have said the waterfront development in Buffalo, an old steel town, is foolhardy.

But the state has kicked in $300 million. Bass Pro Shop has signed on to put a mega-store at the center.

“We just feel we want to be our own people,” Benderson said. “A lot of people who have gone public over the years have been sorry that they’ve done it. This way, we can do our own thing and make our own mistakes, and nobody can criticize what we do.”

Source: https://t-tees.com

Category: WHO