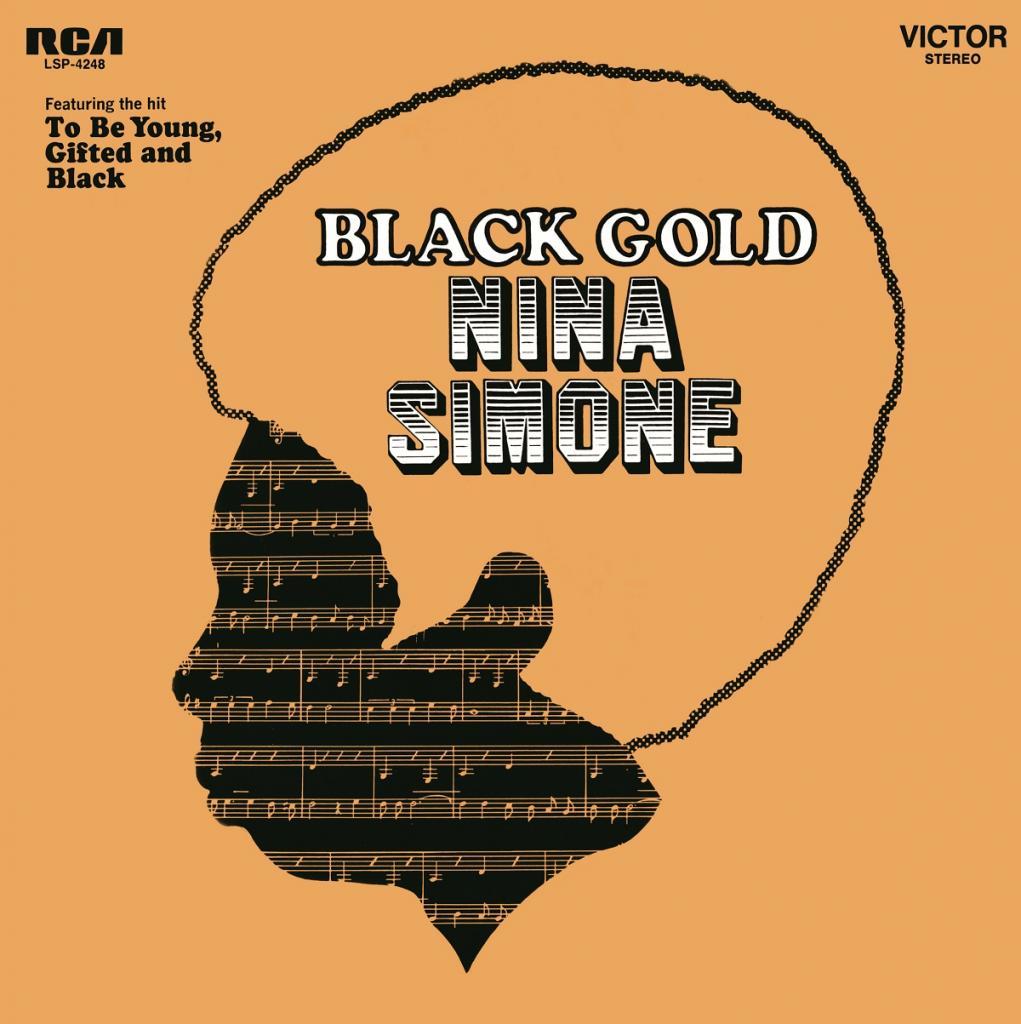

Nina Simone’s haunting reading of Sandy Denny’s ‘Who Knows Where the Time Goes’ was released on Black Gold (1970), a live album recorded during a New York concert in October 1969. Simone was only 36 when she recorded the song but she manages to pour a lifetime’s experience into her rendition. What is perhaps more remarkable is the sense of experience already extant in the original version of the song by the young Sandy Denny (b. 1947). Denny first recorded the song with the Strawbs in 1967, when she was twenty, and again two years later with Fairport Convention (on the album Unhalfbricking). It’s worth dwelling on Fairport’s version before turning to Simone’s.

Nina Simone’s haunting reading of Sandy Denny’s ‘Who Knows Where the Time Goes’ was released on Black Gold (1970), a live album recorded during a New York concert in October 1969. Simone was only 36 when she recorded the song but she manages to pour a lifetime’s experience into her rendition. What is perhaps more remarkable is the sense of experience already extant in the original version of the song by the young Sandy Denny (b. 1947). Denny first recorded the song with the Strawbs in 1967, when she was twenty, and again two years later with Fairport Convention (on the album Unhalfbricking). It’s worth dwelling on Fairport’s version before turning to Simone’s.

The recording opens with the narrator gazing “across the evening sky” at the birds departing for the winter and wondering how they know “it’s time for them to go”. Having set a pastoral scene of herself dreaming before the winter fire, Denny moves into the song’s meditative refrain, the repeated line “Who knows where the time goes?” She lingers on the second “goes”, running it over several resolution bars and musically connecting with bandmate Richard Thompson’s bubbling guitar. As Thompson takes the baton, Denny’s voice fades with her dwindling breath, a reminder of time’s inexorable march. A second verse likens the departure of “fickle friends” to the birds in the first verse. Again, the singer remains rooted to the spot, with “no thought of leaving” and no fear in the passing of time and companionship; again, the refrain sings otherwise, its unanswerable question swept downstream by the music’s relentless current. The third and final verse suggests the singer has a lover near and that it is their presence which banishes the fear of time, along with the knowledge that the birds will return in Spring. In each verse, a claim is made (“I have no thought of time”, “I do not count the time”, “I do not fear the time”) which seems to be disputed by the refrain.

You are viewing: Who Knows Where The Time Goes Meaning

Should we hear the song as one of innocence or experience? Perhaps it is both. On the one hand, it is a song of youthful wonder; experience may not only be unnecessary but it may be the very lack of experience that can command such wonder. The question posed by the young Sandy Denny is a more sophisticated version of the child’s endless “Why…?”, of a seemingly infinite fascination with the world. On the other hand, the sense of childhood’s end, of being abandoned by “fickle friends” and loss of what was taken for granted is palpable. Experience hardens the dreamer and warns that, as the cycle of the seasons turns, so loss will be recurrent on the journey through life. One thus steels oneself against inevitable loss: “I have no fear of time” builds a façade of confidence that the subsequent music cannot support. But just as importantly, the words are timeless and this no doubt accounts for the number of cover versions of the song and of its ability to mean different things at different stages of its performers’ and audiences’ lives.

Read more : Who Has Tessa Brooks Dated

It is possible that Nina Simone heard ‘Who Knows Where the Time Goes’ on Judy Collins‘s album of the same name (1968), given that she attempted to record Collins’s song ‘My Father’ (from the same album) not long after recording Denny’s song. Collins was the first artist to release a recording of the song, having initially placed it on the b-side of her single relaase of Joni Mitchell’s ‘Both Sides Now’ (also released prior to its writer’s own version). Like Collins, Simone changes the first line to “Across the morning sky”, thus suggesting a paradox: if Denny’s version was a song of innocence, why did it start in the evening? Surely this “morning sky” version gets closer to the wide-eyed wonder of the innocent? However, Simone offers a preamble to the song that emphasizes its reflective aspect and makes it clear that she reads the song as one of experience:

Let’s see what we can do with this lovely, lovely thing that goes past all racial conflict and all kinds of conflict. It is a reflective tune and some time in your life you will have occasion to say “What is this thing called time? You know, what is that?” … [T]ime is a dictator, as we know it: where does it go? What does it do? Most of all, is it alive? Is it a thing that we cannot touch and is it alive? And then one day you look in the mirror – how old – and you say, “Where did the time go?” We leave you with that one.

Where Denny’s version of the song with Fairport Convention drew much of its affect from its stately pace, Simone’s derives its power from its use of silence, beginning with the introduction. She speaks very softly, creating an intimacy that invites her audience to start to think about time. Such intimacy can cause an awareness of time’s passing that, contrary to the assertion in Denny’s lyric, brings about fear. Eva Hoffman, describing the “chronophobia” she experienced as a child, recalls reading in the silence of her room and “listening to the clock … aware that each tick-tock was irreversible, and that the stealing of time, second by second, would never stop”. On the other hand, an imposed silence can encourage us to turn to our memory in order to negotiate sensory confusion. As Pierre Nora writes in regard to official silences, “the observance of a commemorative minute of silence, which might seem to be a strictly symbolic act, disrupts time, thus concentrating memory”. As both Nora and Hoffman observe, it is time that allows us to think about time: “the need for reflection, for making sense of our transient condition, is time’s paradoxical gift to us, and possibly the best consolation for its ultimate power” (Hoffman).

Read more : Who Owns Cassena Care

Although ‘Who Knows Where the Time Goes’ engages with chronophobia, it is arguably more concerned with reflection. This is true for the versions by Denny, Collins and Simone; what Simone’s version may be said to add is a sense of “dislocation” that “exacerbates the consciousness of time” (to use Hoffman’s words). This results from the silence and stillness at the heart of Simone’s rendition, a silence which seems to be, paradoxically, even louder on record because of the listener’s knowledge that they are listening to a live recording. The “silence” of the concert hall is not really that silent, as John Cage and others proved long ago, and the addition of audience, equipment and other background noise adds layers of sound against which the fragility of Simone’s stark performance is forced to compete. Initially backed only by a gently strummed acoustic guitar, she slowly sings the first two verses and refrains before taking a brief yet quietly virtuosic piano solo. The sense of reverie is enhanced when, in the first verse, she stretches the word “dreaming” (3:02-3:09) and uses melisma to make the word flutter slightly above the melody, as if relocating the song itself to a space of dreaming and contemplation. During the second verse soft percussion enters (4:15 onwards), a single, steady beat that, at 60 bpm, echoes the ticking of a clock and serves as a reminder of the passing of time. For the third verse the piano is silent again and Weldon Irvine’s organ shimmers ghostlike in the background. The overall impression is one of peaceful, thoughtful reflection and a yearning devoid of any bitterness (it “goes past … all kinds of conflict”). This makes what happens next all the more surprising. Before the final “goes” has disappeared the band comes crashing in, organ, electric guitar and percussion providing what is presumably a climax to the show (“we leave you with that one”). It is a shocking moment, jolting us from our reverie. Time seemed to have stood still, we let it go by, not knowing where it went, unworried until the band returned like a superego telling us to move on from our fantasy. It is both part of the masquerade – the abrupt climax to the show – and brutally honest, suggesting that experience can be a shattering process as much as the gradual one Simone narrates in her introduction. It might also be likened to an alarm clock recalling dreamers to the demands of the day.

Interestingly, when including ‘Who Knows Where the Time Goes’ on the box set To Be Free, the producers chose to remove both Simone’s introduction and the band’s conclusion, allowing it to retain its sense of reverie and to be considered as a song outside the context of the concert, while also making it more directly comparable to versions by Denny and Collins. Mike Butler’s description of the performance (in the CD liner notes to Black Gold) as “a dream encounter between Nina and Sandy Denny” seems entirely apt, even if it is not clear whose dream Butler is referring to. “Dream” captures something of the ethereal, uncanny otherness of this magisterial performance, while “meeting” recognizes that Simone’s version does not replace, better or reinvent Denny’s, but rather encounters it in a timeless and liminal space. Rarely has the fragility of time, space and existence been caught so effectively on tape.

This entry was posted on June 14, 2013 at 3:22 pm and is filed under Lateness with tags folk, fragility, lateness, time, yearning. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

Source: https://t-tees.com

Category: WHO