“God Rest You Merry, Gentlemen” Traditional English CarolWorship & Song, 3052

God rest you merry, gentlemen, let nothing you dismay, for Jesus Christ our Savior was born upon this day, to save us all from Satan’s power when we were gone astray. Refrain:O tidings of comfort and joy, comfort and joy;O tidings of comfort and joy.

You are viewing: Who Wrote God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen

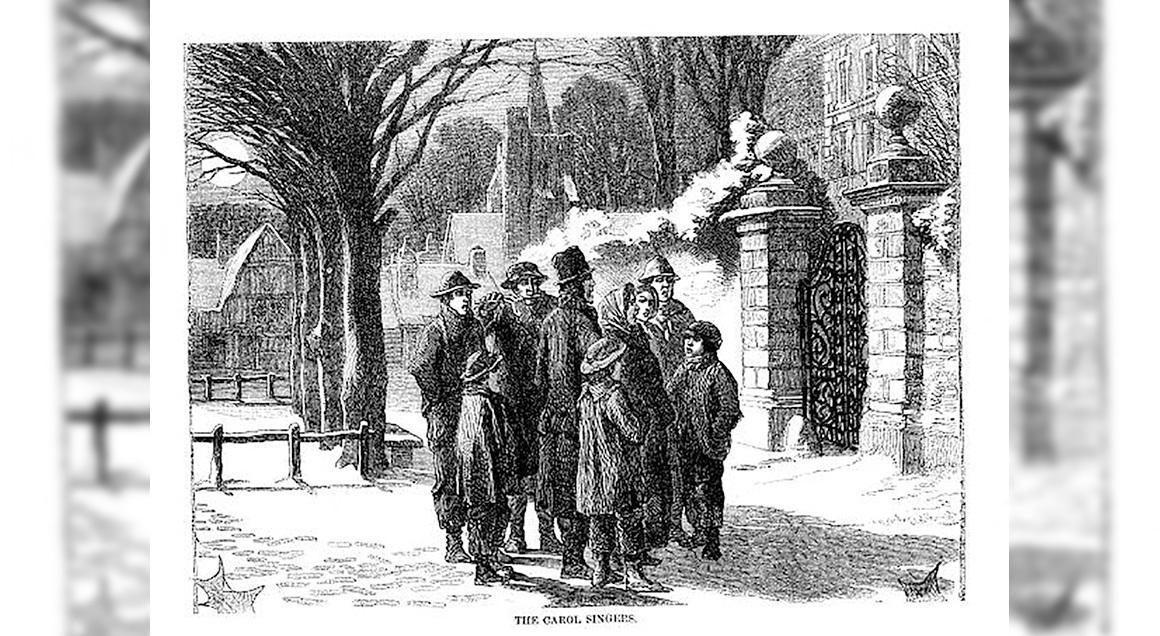

This is a somewhat curious entry in a United Methodist hymnal supplement. Indeed, “God rest you merry gentlemen” does not appear in earlier Methodist hymnals. It is much more likely to be found in Episcopal and Anglican hymnals in the USA, Great Britain, Canada, and Australia, as well as a number of Catholic collections. While selected Protestant hymnals carry the hymn, its apparent English ethnicity conveyed by its language, melody, and possible social use require adaptations to make it appropriate for liturgy. Though its roots are somewhat ambiguous, it seems to have been well known by the time Charles Dickens published his famous A Christmas Carol (1843); when Ebenezer Scrooge heard it being sung outside the door of his office on Christmas Eve, he “seized the ruler with such energy of action, that the singer fled in terror” (Watson, Canterbury, n.p.).

Eminent British hymnologist Erik Routley (1939-1982) classifies this song and “The First Noel” as “ballad-carol.” Rather than the standard hymn meters – Short (6686), Common (8686), and Long (8888) – “God Rest You merry” employs longer three-line stanzas and a refrain associated with many folk ballads (Routley, 1958, p. 50). Unlike “The First Noel,” this carol features only the adoration of the shepherds in Luke 2 and not the appearance of the Magi in Matthew’s account.

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1858) included “God Rest You Merry Gentlemen” in his popular work for baritone, chorus, and orchestra, Fantasia on Christmas Carols (1912), a collage of Christmas folksongs, most of which were collected in southern England by Vaughan Williams and the famous folksong scholar Cecil Sharp (1859-1924), sometimes called the founding father of the folksong revival in England. Stanzas of “God Rest You Merry” are featured throughout the work, sometimes “mashed up” with other carols. The rousing orchestral and choral climax features the following stanza, a conventional New Year’s salutation (Routley, 1958, p. 64), echoed softly by a baritone soloist in the final bars:

God bless the ruler of this house and long may he reign; many happy Christmases may live to see again.God bless our generation who live both far and near and we wish you a happy new year.

Read more : Who Is Desmond Howard Married To

This stanza is usually omitted from hymnals, as it speaks more to a domestic Christmas celebration in the dwelling of the Lord of the Manor. The New Oxford Book of Carols (1992) describes this version of the carol as a “luck-visit song” or a song sung by carolers when visiting a house (Watson, Canterbury, n.p.). Though most of the remaining stanzas present a straight-forward telling of the Christmas narrative (Luke 2:8-16), the “merry gentlemen” in stanza 1 combined with this traditional last stanza call into question its inclusion in many hymnals. Indeed, hymnologist Ray Glover, commenting on its appearance in the Episcopal Hymnals 1940 and 1982, noted: “This is one of the most popular English traditional carols that entered the musical repertoire of the Episcopal Church . . .. It has had, however, a mixed acceptance by hymnal editors of other denominations” (Glover, 1994, p. 105). The incipit, “God rest you merry gentlemen,” needs some interpretation; in the English of the day, the meaning was “God keep you merry gentlemen” (Dearmer, 1928, p. 27).

Exact origins of the carol are difficult to trace, as it has appeared in collections from many places in England including broadsides – large pieces of paper printed only on one side enabling a publisher to disseminate information quickly. Broadsides were commonly used as posters to publicize events and make announcements as well as publishing popular songs and ballads. The most common version with eight stanzas appeared in Christmas Carols Ancient and Modern (London, 1833) by William Sandys (1792-1874), the source upon which most hymnals have based their selection of stanzas. His collection included, according to the subtitle, “the most popular [carols] in the West of England, and the airs to which they are sung. Also specimens of French Provincial Carols.” This was the version that was used for the carol’s appearance in the Episcopal Hymnal 1982 (1985) (Glover, 1994, p. 105). Sandys was an entrepreneur, following this collection with Christmastide, its History, Festivities, and Carols (1852), an immensely popular, though much smaller, compilation. Welsh hymnologist Alan Luff notes that “the introductory material was spun out in a sentimental manner” (Luff, Canterbury, n.p.).

It appears that the editors of Worship & Song drew from Sandys’s version as well. The first stanza is consistent with most popular versions of the carol, establishing the reason for the coming of Christ, “to save us all from Satan’s power / when we were gone astray.” Stanza 2 in Sandys’s collection is slightly modified in Worship & Song: “In Bethlehem in Jewry” in Sandys is changed to “Judah.” This is a straightforward account of the location of Christ’s birth with the addition of an editorial comment at the end of the stanza: “his Mother Mary did nothing take in scorn.” While we cannot be sure of Mary’s emotional state, this phrase seems to indicate that she had no difficulty at all with the long and uncomfortable journey to Bethlehem made under duress as a result of the occupying Roman authorities, rejection by owners of inns for lodging even though her condition was obviously dire, or their final accommodations in a filthy stable. Luke 2 is silent on Mary’s personal feelings until verse 19, “But Mary kept all these things, and pondered them in her heart” (KJV).

The angel comes to the shepherds in stanza 3, an account closely reflecting Scripture (Luke2:9-12). An additional stanza found in Sandys is understandably omitted, since it shifts the focus on the birth of Christ as Savior (John 3:16) to Christ the vanquisher of foes!

“Fear not,” then said the angel,“let nothing you affright, this day is born a Savior, of virtue, power, and might, so frequently to vanquish all the friends [or fiends] of Satan quite.”

In stanza 4, the carol editorializes again, stating that after rejoicing upon hearing the words of the angel, they “left their flocks a-feeding in tempest, storm, and wind.” Verses 15 and 16 in Luke 2 are much more straightforward without comments on inclement weather. It is interesting to think about the angels singing “Glory to God in the highest” in Luke 2:14 while a howling storm was underway.

Read more : Who Is Patricia Richardson Husband

An additional stanza appears here in Sandys:

But went to Bethlehem they came, whereat this infant lay, they found him in a manger, where oxen feed on hay:his mother Mary kneeling, unto the Lord did pray.

Again, the last two lines indicating a prayerful posture by Mary are not biblical – indeed, it is difficult to imagine a woman who had just given birth kneeling in adoration – but an added image indicating Mary’s personal piety and devotion.

The final stanza in Worship & Song (stanza 7; the eighth in the original is cited above) invites all to “sing praises” in response to the good news of Christ’s birth and to embrace one another “with true love and brotherhood.” Curiously, Worship & Song maintains a somewhat enigmatic final line found in Sandys: “this holy tide of Christmas / all others doth deface.” The Episcopal Hymnal 1982 changes this line to: “this holy tide of Christmas / doth bring redeeming grace,” ending on a note of redemption rather than condemnation. For twenty-first century ears, the Hymnal 1982’s modification has more theological integrity and leads more naturally to the refrain: “O tidings of comfort and joy.”

The Music

Historically, two tunes are associated with this text. The first possible printed version of the commonly known version GOD REST YOU MERRY was an instrumental variation by Samuel Wesley (1757-1834), the younger son of Charles Wesley (1707-1788), titled The Christmas Carol, Varied as a Rondo, for the Piano Forte (London, n.d.). It appears that the work was composed in the second decade of the nineteenth century, as a review of it was published in 1815. There are rhythmic variations from the sung version, and the third phrase of the stanza is significantly different from the familiar carol (Glover, 1994, p. 105).

The Oxford Book of Carols (London, 1928) provides two tunes (Nos. 11 and 12). The first version, virtually unknown this side of the Atlantic, is cited as the “usual version” and identified by Routley as “Cornish” (Routley, 1958, p. 89). This was the tune identified by Sandys in his collection. The second version, the one popularly sung today, is listed “as sung in the London streets” (Dearmer, 1928, p. 27). The London tune was collected by E. F. Rimbault (1816-1876), a London organist, and first printed in A Little Book of Christmas Carols, with Ancient Melodies to which they are Sung in Various Parts of the Country (1846) (Firman, Canterbury, n.p.). The melody as we know it was standardized over several publications, a customary process for establishing the commonly known version of a folk tune.

The date of the publication in 1846 may indicate that the less familiar Cornish tune was the melody used in Dickens’s first production of The Christmas Carol (1843). On the other hand, if the commonly known version was being “sung in the London streets” during the decades previous to the publication of the play, then this version may have been used in the performance. From 1919 through 1957, the first two carols sung at the famous Nine Lessons and Carols held on Christmas Eve at King’s College, Cambridge, were “Once in Royal David’s City” and “God Rest You Merry Gentlemen” (Routley, 1958, p. 231).

Source: https://t-tees.com

Category: WHO