On Wednesday, the Treasury Department announced that a portrait of Harriet Tubman will grace future $20 bills starting in 2030. It’s a fitting, and long overdue tribute to a genuine hero of American history who helped end the gravest evil this nation ever perpetrated.

But the department also announced that the man currently on the bill — perhaps America’s worst president and the only one guilty of perpetrating a mass act of ethnic cleansing — will still be on there: Andrew Jackson. This is unacceptable. Jackson was a disaster of a human being on every possible level, and should not be commemorated positively by any branch of American government. And as a slave owner, putting him on the other side of Tubman’s bill is particularly disgraceful.

You are viewing: Why Is Andrew Jackson Bad

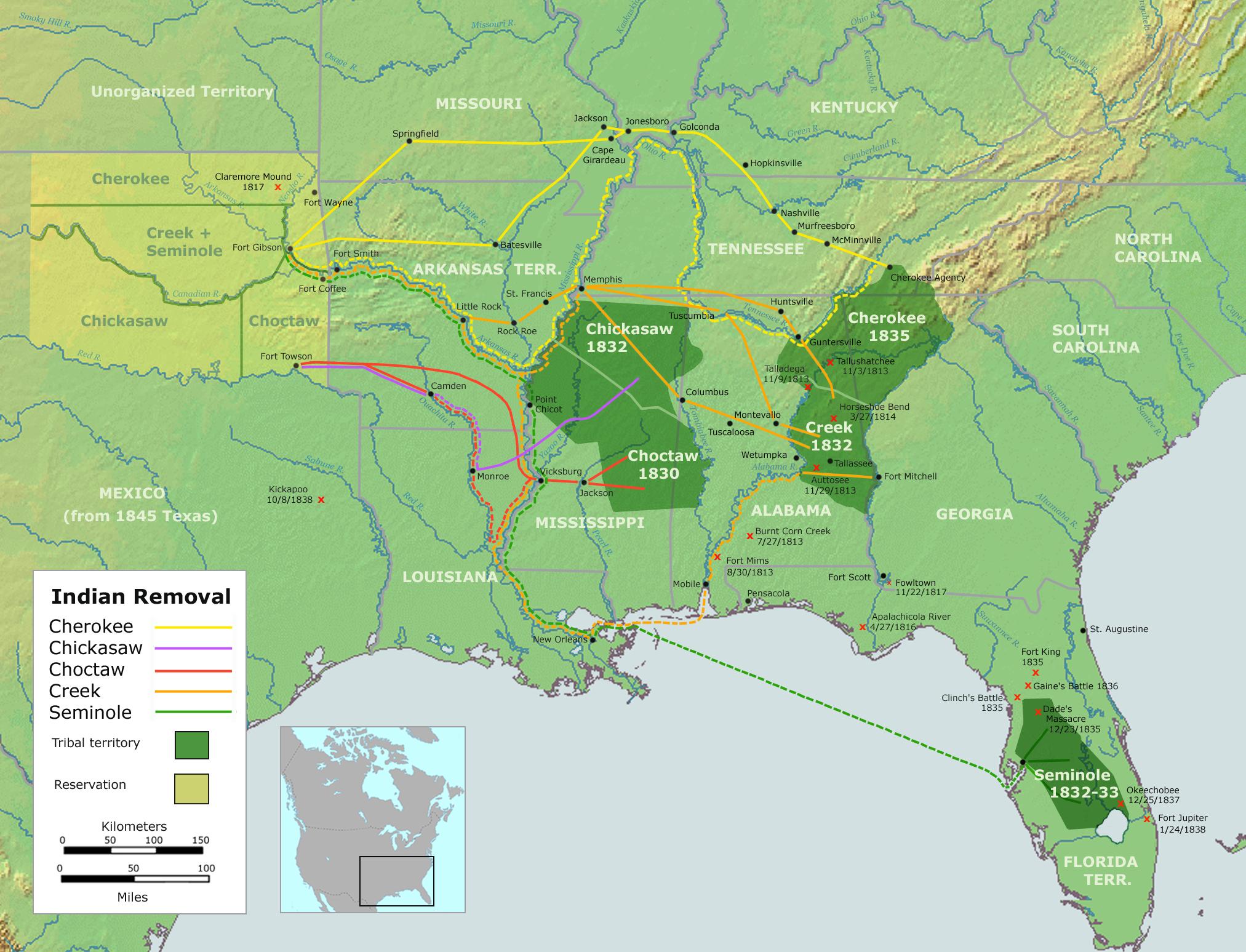

After generations of pro-Jackson historians left out Jackson’s role in American Indian removal — the forced, bloody transfer of tens of thousands of Native Americans from the South — a recent reevaluation has rightfully put that crime at the core of his legacy.

But Jackson is even worse than his horrifyingly brutal record with regard to Native Americans indicates. Indian removal was not just a crime against humanity, it was a crime against humanity intended to abet another crime against humanity: By clearing the Cherokee from the American South, Jackson hoped to open up more land for cultivation by slave plantations. He owned hundreds of slaves, and in 1835 worked with his postmaster general to censor anti-slavery mailings from northern abolitionists. The historian Daniel Walker Howe writes that Jackson, “expressed his loathing for the abolitionists vehemently, both in public and in private.”

Jackson’s small-government fetishism and crank monetary policy views stunted the attempts of better leaders like John Quincy Adams to invest in American infrastructure, and led to the Panic of 1837, a financial crisis that touched off a recession lasting seven years. If that weren’t enough, he was a war criminal who suspended habeas corpus and executed prisoners for minor infractions during his time as a general in the War of 1812.

Andrew Jackson deserves a museum chronicling his crimes and dedicated to his victims, not commemoration on American currency.

Andrew Jackson, ethnic cleanser

Any evaluation of Jackson must begin with American Indian removal, his policy of coercing Native American tribes into leaving their historical territory and embarking on dangerous and often deadly relocations.

Jackson’s support for Native American removal began at least a decade before his presidency. From 1815 to 1820, he served as a federal treaty commissioner dealing with Southern Indians, and “persuaded the tribes, by fair means or foul, to sell to the United States a major portion of their lands in the Southeast, including a fifth of Georgia, half of Mississippi, and most of the land area of Alabama,” the anthropologist and historian Anthony Wallace writes in The Long, Bitter Trail: Andrew Jackson and the Indians. “Andrew Jackson had a personal financial interest in some of the lands whose purchase he arranged.”

But Jackson didn’t only want removal for personal enrichment. He also wanted it as a way to further white supremacy and slavery, and to shore up his Southern support. “The hunger for Indian land was most intense in the Southern slave-owning states, and Jackson as a politician generally reflected Southern economic interests,” Wallace writes. “Jacksonian Democracy … was about the extension of white supremacy across the North American continent,” Howe writes in What Hath God Wrought, his history of the 1815 to 1848 period. “By his policy of Indian Removal, Jackson confirmed his support in the cotton states outside South Carolina and fixed the character of his political party.”

Jackson wasn’t alone; the entire Democratic party was in thrall to the slave power at this point, and receptive to policies like Native American removal that freed up land for slavery. “The exaltation of the common man (meaning, on the frontier, the settler and speculator hungry for Indian land), the sense of America as the redeemer nation destined for continental expansion, the open acceptance of racism as a justification not only for the enslavement of blacks but also for the expulsion of Native Americans — these were popular, politically powerful themes that would have driven any Democratic President to press for a policy of Indian removal,” Wallace writes.

According to Howe, Indian removal was Jackson’s top legislative priority upon taking office in 1829. He quotes Jackson’s vice president and successor, Martin Van Buren, as declaring, “There was no measure, in the whole course of [Jackson’s] administration, of which he was more exclusively the author than this.”

While the law Jackson pushed through Congress in 1830, the Indian Removal Act, theoretically only authorized Jackson to negotiate removal with the tribes, Jackson had no interest in making deals. “To him, the practice of dealing with Indian tribes through treaties was ‘an absurdity,'” Howe writes; instead he believed “the government should simply impose its will on them.”

Read more : Why Are My Mums Turning Brown

Jackson’s stance triggered huge opposition. Evangelical Christians opposed removal as a betrayal of Native Americans, and an impediment to missionary work. Congressional opponents like Sen. Theodore Frelinghuysen assailed it on moral grounds. The proposal only barely passed the House, 102 to 97, with Jackson supporters in the North defecting to the opposition. “The vote had a pronounced sectional aspect,” Howe writes. “The slave states voted 61 to 15 for Removal; the free states opposed it, 41 to 82. Without the three-fifths clause jacking up the power of the slaveholding interest, Indian Removal would not have passed.”

Jackson set about implementing the measure as soon as he was given the authority. “In principle, emigration was to be voluntary,” Wallace writes. “But the actual policy of the administration was to encourage removal by all possible means, fair or foul.”

To weaken tribal chiefs, Jackson’s administration stopped paying them annuities to spend on behalf of their tribes. Some tribes were given tiny individual grants (each Cherokee got 45 cents a year, and then only once they got to the West), others nothing at all. Meanwhile, Southern state governments set about destroying tribal governments, banning tribal assemblies, making it illegal to pass tribal laws, denying Native Americans the right to vote or sue or testify in court or even dig gold on their own land (a provision passed only after gold was discovered).

Jackson’s administration stood idly by and let it happen, knowing that the more Southerners harassed Native Americans, the easier it would be to coerce them into removal treaties. “It is abundantly clear that Jackson and his administration were determined to permit the extension of state sovereignty because it would result in the harassment of Indians, powerless to resist, by speculators and intruders hungry for Indian land,” Wallace concludes.

The first post-Act treaty, the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek on September 27, 1830, securing Choctaw removal, was achieved “against the wishes of the majority of the tribe, by excluding the Indians’ white counselors from the negotiations and then bribing selected tribal leaders,” Howe writes.

Once Jackson’s administration secured its fraudulent treaties, it set about the actual process of removal. From the very beginning, the process was deadly. About four thousand Choctaws died of cholera, and hundreds more died from hunger, exposure, and accidents, per Wallace. A steamboat carrying 611 Creeks up the Mississippi collided with another boat and was cut in two, killing 311 Indian passengers. Anywhere from 20 to 25 percent of Eastern Cherokees died either being rounded up or transported West.

The problem was not one of faulty implementation; Jackson’s own actions made the process of removal bloodier and crueler. “During the Removal process the president personally intervened frequently, always on behalf of haste, sometimes on behalf of the economy, but never on behalf of humanity, honesty, or careful planning,” Howe writes. “Army officers like General Wool and Colonel Zachary Taylor who attempted to carry out Removal as humanely as possible or to protect acknowledged Indian rights against white intruders learned to their cost that Jackson’s administration would not back them up.”

The actual death toll of removal is uncertain. The toll for Cherokees alone is typically given as 4,000 to 8,000, per Amy Sturgis’s book, The Trail of Tears and Indian Removal. But thousands more Creek, Choctaw, Seminole, and other Indians died in the process as well, direct victims of the signature policy of the Jackson administration.

Andrew Jackson, laissez-faire zealot

It’s genuinely bizarre that some modern liberals, like Sean Wilentz and Arthur Schlesinger, have claimed Jackson for liberalism, ostensibly for his embrace of “populism” (read: rejection of northern anti-slavery white men in favor of Southern pro-slavery white men). In reality, Jackson’s economic policy views were almost cartoonishly right wing.

Context is important here. Jackson was succeeding John Quincy Adams, a truly great, scandalously underrated president who was an enthusiastic supporter of government intervention to build necessary infrastructure (“internal improvements”) and fuel economic development. Adams believed that “taxing and being taxed were essential to responsible self-government; the country required a modern, national, and regulated banking system … and the federal government had an important role to play regarding the ‘general welfare’ in the creation of educational, scientific, and artistic institutions, such as the Smithsonian Museum, the national parks, the service academies, and land grant universities,” according to recent biographer Fred Kaplan.

Jackson believed none of that. He believed government was a threat to be contained, that national banks like the one originated by Alexander Hamilton were abominations and threats to freedom, and that the federal government’s role in building infrastructure should be limited. He vetoed a bill to run a road in Kentucky, arguing that federal funding of such infrastructure projects was unconstitutional.

“While he criticized the Maysville Road for being insufficiently national, Jackson did not wish to be misunderstood as favoring federal funding for a more truly national transportation system,” Howe writes. “Instead he warned that expenditures on internal improvements might jeopardize his goal of retiring the national debt — or, alternatively, require heavier taxes.” The veto, Howe continues, ultimately led to “the doom of any comprehensive national transportation program.”

Read more : Why Did My Girlfriend Break Up With Me

Jackson was a strict adherent to the gold standard, a position as silly in the 1830s as it remains today. This directly informed his war on the Second National Bank of the United States. “That the modern twenty-dollar Federal Reserve Note should bear Andrew Jackson’s portrait is richly ironic,” Howe writes. “Not only did the Old Hero disapprove of paper money, he deliberately destroyed the national banking system of his day.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/assets/4640491/trailoftears_robert_lindneux.jpg)

Contrary to Jacksonian propaganda, the Second National Bank worked quite well. It produced reliable paper currency of consistent value across the country. But Jackson, as an avowed opponent of paper money and of national economic institutions like the Bank, vetoed the renewal of its charter in 1832. His rhetoric against the bank drew upon populist anti-bank sentiment, but its real crime in Jacksonian eyes was propping up a powerful government. “The advocates of hard money did not condemn banks as agents of capitalism,” Howe writes. “They condemned them as recipients of government favor.”

Jackson’s war on the bank, combined with his intent on paying off the national debt, would lead to one of the worst depressions in American history. Once the government started running a surplus, Jackson had nowhere to put the money, without the bank around. So he divided it among the states. “The state banks went a little crazy,” Planet Money’s Robert Smith explains. “They were printing massive amounts of money. The land bubble was out of control.” Before long you had the Panic of 1837, and years of recession.

Not all economic historians accept this story of the Panic. Others think Jackson screwed up in other ways that caused it. Vanderbilt’s Peter Rousseau, for instance, blames two actions Jackson took in 1836 — requiring public lands be purchased with coins rather than paper money, and “supplemental” transfers of money between banks by the Treasury that summer — for causing the crash. This interpretation, Rousseau writes, “calls into question claims that the nation’s seventh President was an innocent bystander and casts serious doubt on his financial wisdom.”

Andrew Jackson, war criminal

Leaving aside whether Jackson’s acts of ethnic cleansing against Native Americans technically count as war crimes or just ordinary crimes against humanity, his career as a general included numerous actions which would absolutely warrant criminal action today.

Before and after Jackson’s career-making victory in the Battle of New Orleans in 1815 — won after the war was technically over — he ruled the city as a tyrant, as Caleb Crain notes in the New Yorker:

He censored a newspaper, came close to executing two deserters, and jailed a state congressman, a judge, and a district attorney. He defied a writ of habeas corpus, the legal privilege recognized by the Constitution which allows someone being detained to insist that a judge look into his case. Jackson was fined for his actions, and, for the rest of his life, was shadowed by the charge that he had behaved tyrannically. In retirement, after two terms as President, he called on his reserves of political clout to get the fine refunded, and Congress ended up debating the legality of his actions in New Orleans for nearly two years.

On December 16, 1814, Jackson declared martial law, provoking an immediate backlash on civil liberties grounds. “Despite the constitutional irregularity, Jackson imposed a nine o’clock curfew and required that everyone entering and exiting the city be vetted by the military,” Crain explains. He arrested a state legislator who had resisted calls to suspend habeas corpus, and then ordered the man guarding the legislator to arrest anyone trying to serve a write of habeas to free him.

Jackson also had a penchant for executing people — soldiers, enemies, whatever — for little or no reason. In 1818, he famously ordered two British subjects, Robert Ambrister and Alexander George Arbuthnot, executed during the First Seminole War in Spanish Florida. He believed that both were helping the Seminoles wage war against the US. This was most likely not true.

“Arbuthnot … claimed he had only sought the Natives’ welfare and had actually tried to dissuade them from warmaking; this was probably the truth,” Howe writes. “Ambrister had indeed been helping the Seminoles prepare for war — but against the Spanish, whose rule in Florida he hoped to overthrow.”

Arbuthnot was sentenced to death after a trial, and Ambrister to flogging and hard labor. Jackson increased Ambrister’s sentence to death and carried both sentences out the next day “so there would be no chance of an appeal,” Howe recounts. “A former justice of the Tennessee state supreme court, he must have known the convictions would not stand up to appellate scrutiny.”

He also killed some of his own men for petty infractions. While in charge of New Orleans, “six militiamen who had tried to leave before their term of service expired were executed in Mobile by his orders, a draconian action at a time when everybody but Jackson considered the war over.”

Andrew Jackson was an executioner, a slaver, an ethnic cleanser, and an economic illiterate. He deserves no place on our currency, and nothing but contempt from modern America.

Source: https://t-tees.com

Category: WHY