Editor’s note: Sinéad O’Connor died on July 26 at the age of 56. To honor the singer’s legacy, KCRW is resurfacing an interview published on June 7.

In her new book, “Why Sinéad O’Connor Matters,” journalist Allyson McCabe admits she did not always have a soft spot for her subject.

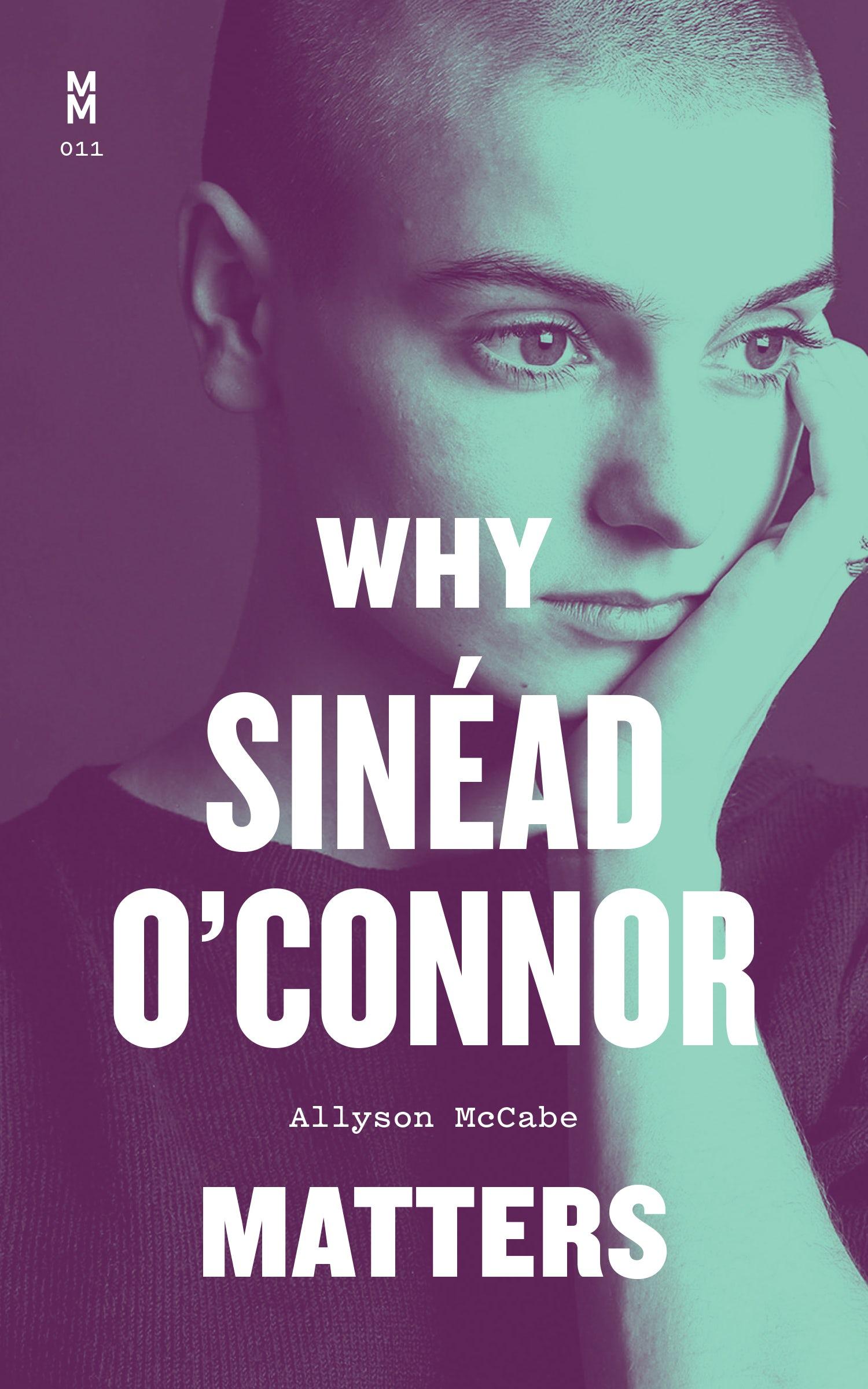

You are viewing: Why Sinead O’connor Matters

“Even after her infamous 1992 appearance on SNL,” McCabe writes, “I probably saw her as indistinguishable from Michelle Shocked or Ani DiFranco, or any of the local queer-adjacent folkies playing in the coffeehouses in and around Northampton, Massachusetts. On campus, virtually every girl, including my roommate, had a shaved head and combat boots. If you wanted to be radical there, you had to do a lot more than tear up a photo of the pope.”

Sinéad O’Connor on Saturday Night Live, October 3, 1992

For most of America, though, tearing up a photo of the pope was more than enough. The incident effectively torched the Irish singer’s commercial prospects in this country, although O’Connor is fond of saying the debacle re-railed, rather than derailed, her career.

The thing about narrative, though, is that it’s largely dictated by forces out of your control. And until very recently, most people unthinkingly accepted the narrative that had stuck to O’Connor for three decades. McCabe herself was among them until January 2020, when she had a chance encounter with a pair of Fiona Apple videos on YouTube. Apple posted the videos in the wake of O’Connor’s own distraught missive from a New Jersey Travelodge in August 2017. (Google if you must.)

Fiona Apple appreciates Sinéad O’Connor at the 1989 Grammys

In the first video, Apple is seen on her bed, rocking out to Sinéad’s performance of “Mandinka” at the 1989 Grammy Awards. At the end, she turns to her dog and says, “I know! She’s the fucking best! She’s our hero!” The second video is filmed only moments later, her dog still in the background. In it, she addresses the camera (and Sinéad) directly: “I just saw the [New Jersey] video of you, and I don’t want you to feel like that.”

A message to Sinéad O’Connor from Fiona Apple

Prior to this moment, McCabe — a music, arts, and culture reporter based in New York — was not particularly attuned to O’Connor’s whereabouts. “I was working on something completely different when I encountered this Fiona Apple video,” she explains.

But McCabe had already been privately reflecting on her own experiences of “loneliness and anguish,” as she says of O’Connor’s video. “I realize I haven’t just been clicking on videos,” she writes. “I’ve been getting closer to the heart of my own story.”

More: Lost Notes: The identity and mystery of jazz pianist Billy Tipton, with Allyson McCabe

The next year, Apple shared a cover of the Waterboys’ anthemic ode to a visionary spirit, “The Whole of the Moon,” which McCabe interpreted as another devotional offering to O’Connor. O’Connor’s memoir, “Rememberings,” arrived a few months later. By now, McCabe felt the steam gathering. She produced a story about O’Connor for NPR, netting an interview with the singer and including commentary from Jessica Hopper and Kathleen Hanna.

“Had things gone a bit differently, maybe I would have left it there and just had that story,” she reflects. “But at that point I was already really deep in. And I wanted to keep going.”

McCabe found a publishing partner in the University of Texas Press. But as she made inroads into the story, she was struck by the parallels between her own formative years and those of O’Connor’s. As McCabe would write in the final manuscript, “Insofar as O’Connor’s talents are inseparable from her struggles and triumphs, so are mine and yours.”

Her editor encouraged her to write a different kind of book: one that deliberately leaned into the consonances between their lives – particularly around McCabe’s religious upbringing, the concomitant sense of shame and disconnection, and the extremely narrow view of what is possible, or even desirable, in a life. In so doing, the story became at once more intimate and more universal – a different animal from O’Connor’s autobiography and Kathryn Ferguson’s subsequent documentary.

Author Allyson McCabe explores the consonances between her life and that of the Irish pop singer in her new book, “Why Sinéad O’Connor Matters.” Photo: Ebru Yildiz.

Author Allyson McCabe explores the consonances between her life and that of the Irish pop singer in her new book, “Why Sinéad O’Connor Matters.” Photo: Ebru Yildiz.

“Ultimately I needed to take down all the scaffolding that we put up as journalists around a story to obscure the fact that we’re in it,” McCabe explains. “I wanted to own the idea that I was talking about Sinéad [while] also talking about the culture and my relationship to the culture as a journalist, and as a human.”

The final product, then, is about much more than Sinéad O’Connor. The singer becomes a “window and a mirror into culture,” as McCabe puts it, expanding far beyond SNL, MTV, Bob Dylan, Prince, or any of the well-trod touchstones of O’Connor’s early career. Instead, the story reaches deeper — more about the refractions and the shadows that O’Connor casts on ourselves and on the culture. It asks the reader to consider their own relationship to the forces that once leveraged themselves en masse against O’Connor. It’s a beautiful and compassionate meditation on silence, trauma, healing, and much more.

Read more : Why Is Vegemite Banned In The US?

“When I thought about who was going to read this book, it wasn’t just for people who are fans of Sinéad,” she says. “I really wanted people to feel like, whatever thing they’ve been holding, what if we all could be heard? What if we all could come out from those locked rooms? That’s the way we heal together.”

Sinéad O’Connor, “Thank You for Hearing Me”, The Late Late Show, May 2020

Ahead of McCabe’s in-person presentation of “Why Sinéad O’Connor Matters” at Book Soup (in conversation with musician and podcaster Allison Wolfe) on June 7 at 7 p.m., the author reflects on O’Connor, trauma, silence, and healing.

“Why Sinéad O’Connor Matters” by Allyson McCabe (University of Texas Press)

“Why Sinéad O’Connor Matters” by Allyson McCabe (University of Texas Press)

KCRW: You had a brief from your editor to put more of yourself into this book than you might have otherwise. How did you approach the challenge of writing in this somewhat counterintuitive way?

Allyson McCabe: As a journalist, you’re so conditioned to suppress your relationship to the material, or your own ideas or feelings about it. [So] doing the opposite was an exercise in thinking: “What is my purpose as a journalist?”

And I want to start by saying, facts do matter. Facts are important. Facts are step one, but they’re not necessarily the last step. People tell you things, but they forget, or they leave things out, or they include things that didn’t actually happen. Part of our job is to sort that out and get to the best possible version of the story that you can.

That involves figuring out what’s true, but it’s also about understanding what happened on an emotional level, not just on a factual level. So I think being in touch with your own reactions will probably get you closer to the thing that journalism calls “neutrality” more than pretending we’re objective.

There’s a moment in the book where you admit to favoring a particular version of a story by saying that it’s “the one that rings most emotionally true.” And I think acknowledging that you’re going for emotional truth is a really lovely way of encouraging readers to attune to that wavelength of Sinéad’s story.

I’m not really trying to write a comprehensive biography. For me, it was more important not to capture every moment that happened in Sinéad’s life. It was more about figuring out where to put the focus, so we can understand where she was coming from in a way that hasn’t happened so much in the past, or even in her own account.

I think one of the things that happened with the SNL tearing of the photograph of the pope is that she didn’t explain, “This is what I’m doing and why I’m doing it.” And maybe some of the reaction might have been different, had she been able to articulate it. But I think she was responding to trauma in a lot of ways, and it wasn’t fair for us to imagine that she’s going to calmly go out and explain, “Hey, this photograph belonged to my mother, and here’s the connection to the Church, and here’s the thing that I’m trying to sound the alarm about,” and all the things that we know now.

Sinéad O’Connor, “Mandinka,” 1989 Grammy Awards

But also, who would have listened to her if she had? When critic Jon Pareles called her “a rock-and-roll Cassandra” — that’s true in more ways than he knew at the time.

I talk about how, early on, you see her performing “Mandinka” at the 1989 Grammys, which is her first public prime-time appearance, at a time when everybody was actually watching the Grammys. And I say it’s like witnessing a fragile catharsis, because she’s tearing apart this false self and trying to put together her own self and present that. And that’s what I saw in the first Fiona Apple video, in the reaction video of watching [Sinéad] perform.

And I was thinking about Sinéad’s later shows, the ones on the West Coast that happened before the pandemic [in February 2020]. To me, it’s like watching Joni Mitchell as a young woman doing “Both Sides Now,” and then seeing her do it later. She’s out there saying, “This is who I am now,” and I think the resilience is what people are responding to, the things that she’s been through. I feel like a lot of people think Sinéad just stopped after 1992, but that’s completely untrue. She’s steadily put out all kinds of music, and I think she’ll continue to do that.

Sinéad O’Connor, “I Believe In You” (Royal Albert Hall, 1999)

The question of “Why Sinéad O’Connor Matters” is not about her, but about what she represents.

Sinéad is both a window and a mirror into culture. And I think that gives us an opportunity to make that connection you’re talking about, which is [that] we can’t talk about her without also talking about ourselves.

How did learning more about Sinéad’s journey help you contextualize or understand your own?

Read more : Can You Be Detained Without Being Told Why

The one thing Sinéad has always done is to push back against shaming and silencing by talking. Talking doesn’t guarantee that the world is going to change, but if you don’t, it certainly won’t. So it forced me to say, “What is the story that I’m holding?” And the value isn’t just, “I’m telling you this for me.”

It’s for you to think about the stories you’re holding, and what it means to release those stories and to be heard. Because I think if we had listened to Sinéad as much as we had judged her over the years, we would actually be in a better place as a society. So it’s not just about the impact on Sinéad that we didn’t do that — it’s about the impact on us as well.

Right. What was the cost?

Exactly. And I [had] to go back and re-experience all those things that were difficult in my own upbringing and in my own experience. For a long time, I ran from those things, and tried to cut them off from who I was. But going back to emotionally experience them also allowed me to process them and grieve them, and it was cathartic.

To connect it to Sinéad’s music, one of her songs from 1994 is called “Famine.” And it connects the experience of the Irish people to her own experience of being an abuse survivor. One of the things she talks about in the lyrics is [that] burying or forgetting the past is not really the way to heal from it. There has to be acknowledgement and forgiveness. Thinking about that really deeply allowed me to go through that process of healing too.

Sinéad O’Connor, “Famine”

It’s one thing to talk about your trauma, but another to integrate it, and then to be able to speak about it in such a lucid way. It’s not the same as just drafting a book. How did you get there?

I would say I was in a place in my life where I was ready to do that anyhow. Back in spring of 2020, I had the “OG” COVID. And it almost took me out, for real, out of this world. So, even before I started working on this book, that experience propelled me into a need to come to terms with and understand different parts of my life that I had cut myself off from before.

Do you think that’s why Sinéad was on your mind? Is there a connection between those two things?

I’m not sure I can smash this into a short answer, but watching Fiona Apple do “The Whole of the Moon,” you get the sense that she’s not just singing a song. It’s about something different. What she’s doing in that video is really powerful, emotionally. And then seeing Fiona’s sadness in the video where she’s reacting to Sinéad’s sadness, then watching Sinéad’s video [in the New Jersey Travelodge in 2017]. I think those things put me in touch with my own sadness in a way that, in the past, I might have been like, “Turn it off. It’s too much. I need to stop, put it down.” But what I was able to do in that moment was think about what was making me have that reaction.

Fiona Apple, “The Whole of the Moon”

We talk as journalists about being guided by curiosity, but in my case, I think it was more compassion. The compassion that I was able to extend to Sinéad, I was able to extend to myself. And that, for me, was the connection.

One of the things that happens when you’re an abuse survivor is that you don’t want people to know about it, because there’s a lot of shame still attached to it. Even though it’s something that happens to you rather than something you did. You feel like people perceive you to be damaged, right? So there’s a lot of denial that people put on that. But I think owning it, for me, actually felt like being stronger than before. Because I was able to say, “Yeah, you know what, that did happen, but it doesn’t define who I am.” And it ended up being about going back and reclaiming even the parts of yourself that are broken, because they are all still a part of you.

Your experience is part of the way you see the world, and it doesn’t mean that you’re less than anybody else. It means, actually, that you are strong, you survived, you’re still here. And while you’re here, you have a kind of responsibility to help other people, in as much as you can. And, you know, a book is only a book. But when I thought about who was going to read this book, it wasn’t just for people who are fans of Sinéad. I really wanted people to feel like, whatever thing they’ve been holding, what if we all could be heard? What if we all could come out from those locked rooms? That’s the way we heal together.

Sinéad O’Connor, “The Wolf is Getting Married” (The Graham Norton Show, 2012)

Of all the relationships you explore in your book — the artist to their own history, the artist to the media, the media to the broader culture — the one that still feels sacrosanct in the end is the relationship between the artist and their audience; the people who listen with compassion, and who honor the artist as a whole person.

And what occurs to me is that, through every terrible and tumultuous thing that’s happened in Sinéad’s public life, there has always been this silent circle holding space for her. And that’s what the Fiona Apple reaction video brings home — that this deeply personal, invisible connection is what keeps an artist alive, even if not necessarily literally. It’s the one thing that can’t be savaged by the industry or the media or religious doctrine or misogyny or our false narratives around mental illness and trauma. Every Sinéad O’Connor fan could write their own book on why she matters, and it would contain more truth than any of those things could possibly conceal.

The book has only been out for a little while, and I’m not on social media, but I’m shocked by the number of people who have written to me about their own experiences of what Sinéad means to them. Sometimes it’s hard to read the letters, because they tell me all about their lives, and why and how they connect to her music, and what she means to them. It’s not just like you are alone listening to a song, but there are so many people who are listening to these songs, and have for so long. And we’re all connected to each other in a way that maybe not every artist has that kind of fan base. There’s a general feeling that music can give us, and then there are certain artists that, I think, do get us to a deeper level of connectedness to our truest selves. And I think she falls into that category.

Even when things were hard, when she’s on stage and it’s just her singing, she’s in her full, you know? In those moments, all the other stuff is noise, You’re able to tune it out and just be like, “Oh, wait, this is what it’s about.” She is an artist, and an artist isn’t just there to entertain you or make you feel comfortable. An artist is there to express an emotion, and for you to also be able to access that emotion yourself and experience it. And that’s when I think music becomes cathartic, even when it’s difficult.

Sinéad O’Connor, “Troy” (Night of the Proms, Belgium, 2008)

Source: https://t-tees.com

Category: WHY