This is a story of two wars. One, in Joseph Heller’s novel Catch-22 first published in 1961, is a fictionalised version of WW2; though by the latter 1960s and early 70s, many of its readers would relate its satirical anti-war message directly to the real war in Vietnam.[1] The other, the Pentagon Papers (1969), was a work of fact about the real Vietnam War, which revealed that for years, many of the supposed truths that the American people had been told by their leaders about American involvement in Southeast Asia were, in fact, fiction. As part of Banned Books Week, Nick Berbiers, Library and Information Adviser, is going to take you through the facts and the fiction.

Welcome to early 1970’s America, a strange through-the-looking-glass place: a fractured and confused society where old and young and government and people no longer seemed to share common values and perceptions or even speak the same language. It was a land riven by a hugely divisive real war taking place halfway across the globe, when, surreally, at precisely the same moment, a fictional war was regarded by some Americans as highly threatening. It was a country where some believed that both a fictional war story and the facts about a real war should both be supressed. In the context of those strange, tortured times, this blog considers who or what was threatened by the publication of the Pentagon Papers and Catch-22.

You are viewing: Why Was Catch 22 Banned

Part IV C 9a of the full release of the Pentagon Papers, 15 January 1969, Pentagon-Department of Defense, Archive.gov via Internet Archive, via Wikimedia Commons.

The historical challenges

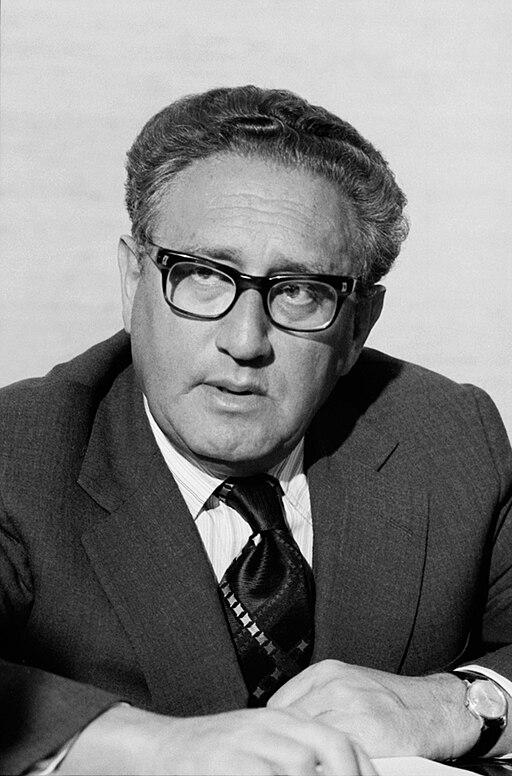

Before proceeding to the Pentagon Papers themselves, it is worth observing that there are two distinct challenges that one faces when writing about their history. Firstly, there is the problematic issue that anything to do with the Nixon Administration is affected by the pall of Watergate, forever hanging over the president and his subordinates, making it all too easy to see dark motives in everything they did from 1969-74. One should though, be at pains to avoid being blindsided by Watergate, not only for its effect upon historical objectivity but also because viewing everything that Nixon did through that particular lens is far too simplistic and often just straightforwardly wrong. The second is the need to maintain a tight focus on the primary issues in regard to the Pentagon Papers – who was threatened by their publication? – rather than deviating off into all sorts of admittedly fascinating related areas. All else aside, the key issue comes down to two men whose reactions to the first in a series of intended publications of the Pentagon Papers by the New York Times on June 13, 1971, determined everything that the US government did next. Those two men were Richard Nixon, President of the United States, and Henry Kissinger, his National Security Advisor.

Marion S. Trikosko., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Richard Nixon’s congressional portrait, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Nixon and Kissinger react

The Pentagon Papers is a euphemism that quickly developed for a seven thousand page study of the history of US involvement in Vietnam, commissioned by President Johnson’s Defence Secretary Robert McNamara in 1967, which comprised both classified intelligence and military analysis, coupled with copies of top secret government documents. The complete study was leaked in full to the New York Times by Daniel Ellsberg, a former soldier, economist, and ex-government employee who had himself contributed to the military analysis in the Pentagon Papers but then subsequently turned against the war.[2] The exhaustive (and exhaustingly numerous) memoirs, biographies, and histories of the Nixon presidency can essentially be split into two competing accounts of how the president first reacted to the entirely unexpected publication of the first set of these papers on June 13, 1971. Either, he was immediately infuriated, or he was surprised though relatively unconcerned until Henry Kissinger spoke to him by telephone that afternoon.[3] As that telephone call is recorded for posterity on the infamous Nixon tapes, we shall first proceed with that ‘best evidence’.

In support of his later description of his own private reaction to the publication (see note 3 below) Nixon does say in this early conversation, “…this is treasonable action on the part of the bastards that put it out”.[4] Later in the call, Kissinger comments: “It’s treasonable, there’s no question . . . I’m absolutely certain that this violates all sorts of security laws”.[5] It is important to note here that no commentator has ever suggested that either Nixon or Kissinger had actually read McNamara’s study in full or were aware of precisely which sensitive government documents it contained. The pair were reacting off the cuff to what the Times had published that first day whilst announcing in broad terms what it would serialise over coming days and week. Even without all the details, this was a highly concerning scenario from Nixon and Kissinger’s point of view, bearing in mind that the war was still raging whilst they made various efforts, some through secret ‘backchannels’, to broker a peace deal.

What many historians and biographers highlight, knowing from both the presidential tapes and various memoirs how sensitive Nixon was to any appearance of weakness, is the part of the taped conversation where Kissinger says to him: “It shows you are a weakling, Mr President”.[6] By 1971, the National Security Advisor, who clearly wanted a strong response to the publication of the Papers from Nixon, was well aware that this sort of comment would be guaranteed to galvanize his boss to action.[7] He was not suggesting that the contents of the Pentagon Papers themselves made Nixon look weak as they did not include any material relating to the Nixon presidency, but rather that the theft of the papers and their leaking and publication did.

The threat is identified

What then, more precisely than this early phone call articulates, was the threat posed by the Pentagon Papers? Here we must turn to Nixon and Kissinger’s written accounts, describing the threat assessment that they received from within government in the days following the first publication. In his memoirs, Nixon notes that all the materials that comprised the Pentagon Papers ‘were still officially classified “Secret” and “Top Secret”. In fact, this was the most massive leak of classified documents in American history.’ [8] And he observes, ‘An important principle was at stake in this case: it is the role of government, not the New York Times, to judge the impact of a top secret document.’ [9] So, what was this impact potentially? Here it is worth giving Nixon’s assessment in detail:

The National Security Agency was immediately worried that some of the more recent documents could provide code breaking clues…[to the] trained eyes of enemy experts. The State Department was alarmed because the study would expose Southeast Treaty Organisation contingency war plans that were still in effect. The CIA were worried that past or current informants would be exposed…A tremor shook the international community because the study contained material relating to the role of other governments as diplomatic go-betweens…Dean Rusk issued a statement that the documents would be valuable to the North Vietnamese and the Soviets. [10]

Kissinger agrees with Nixon, making very similar points in his memoirs.[11] Objectively then, considering the assessed nature of the threat that the government faced in this initial period, the president and his National Security Advisor’s concerns are not that unreasonable. Potentially, from their point of view, international relationships could have been severely damaged. Even more importantly, they believed that lives were being put at risk by publication and the chances for peace jeopardised: indeed, they were both at pains to reiterate these points when looking back on these events many years later.[12] Thus, the

government went to court to try and seek an injunction banning any further publication of the Papers: an effort which failed when the Supreme Court ruled that that “the Government had not met its heavy burden which might justify a prior restraint” (i.e. it had not proved its case) [13], thus opening the way for the Pentagon Papers to be published in full. The extent to which Nixon and Kissinger’s initial fears did not come to pass – for there is little evidence that publication did have the effects that they were concerned about – is not really the point. The serious threat, as they perceived it in those early days immediately after the first serialisation, was real and present in their minds, and thus it is quite possible to understand and sympathise with their desire to suppress the classified material.

Attorneys huddle during the Pentagon Papers trial in 1973, as rendered by David Rose, SheBeHuman, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

A School Board’s reaction to Catch 22

The following year, negative sentiments would develop in members of a city school board relating to writings on another war; though on this occasion, the book was entirely fictional.

Judging by its frequent appearances in ‘best-ever’ novel lists, Joseph Heller’s satirical Second World War novel Catch-22 is widely regarded a modern classic.14 Published in 1961, there are no recorded cases of any attempts to ban it until 1972 when the Strongsville City School District, Ohio, removed it from its curriculum and school library. So long after its first publication, it is entirely possible that the 1970 film adaption of the same name put the novel firmly back on readers’ radar.

The process which led to the initial ban of the book was lengthy and complicated. To summarise, in 1972, an English teacher at the Strongsville City School recommended that Catch-22 – which, somewhat perversely in light of subsequent events, was already available in the school library [15] – should be added to the curriculum as mandatory reading for the following year’s senior English classes. [16] Any such recommendations had to be considered by a Faculty Textbook Selection Committee made up of “sixteen individuals who lived in the school district…selected, in part, by Board members and the PTAs of the designated schools within the district”.[17] After consideration, the committee recommended that Catch-22 should be excluded as a required text, and following various administrative and review processes the school board then formally excluded the novel from the curriculum as being “objectionable” and also had it removed it from the school library.[18] Fairly or unfairly, it is easy to imagine these various locally-engaged citizens as personifications of Nixon’s so-called ‘Silent Majority’: conservative, patriotic, government-respecting, and God-fearing.[19]

The legal fight

Very few relevant documents, such as the minutes of meetings from 1972, are in the public domain, so one has to turn to the subsequent legal proceedings to get a sense of the Board’s original objections in 1972 to both Catch-22 and other novels that they decided to exclude

Read more : Why Can’t Romeo And Juliet Be Together

from the curriculum. These objections were summarised by District Judge Krupansky in 1974 as “reflect[ing] an attitude that the proposed novels were adult-orientated and, therefore, less suitable for use as curriculum text for grades 10 through 12 than other available novels, and that the books were better suited for college level instruction and study”.[20] As frustratingly vague as this is, it seems reasonable to postulate from this information, if only as a preliminary hypothesis, that in terms of perceived threat the Board regarded the 16-18 year old students as being at risk in some sense if they read Catch-22. Whether this related to Heller’s overarching message about the futility of war, or the subversive notion that “The enemy is anybody who’s going to get you killed, no matter which side he’s on” [21] is debatable. Equally, there may have been a reaction against Heller’s religious despair – “He’s not working at all. He’s playing or else He’s forgotten all about us” [22]. Perhaps the thought that such material might be read by students whilst the Vietnam War raged on – a conflict which was conceivably still being supported by some Board members – would instil undesirably (from the Board member’s point of view) sacrilegious, anti-patriotic ideas in young minds. What is clear and noteworthy though, is that it was five of these self-same supposedly immature, vulnerable students who then pursued a First and Fourteenth Amendment court case against the school district with the support of their parents and the ACLU, arguing that their “constitutional rights to academic freedom…due process, and equal protection of the laws by the commission of acts which impose prior restraints upon publications and communications” had been violated.[23] Clearly, the students themselves and their parents took the view that they were under no threat whatsoever from studying Joseph Heller’s novel. Perhaps in a world where sons and older brothers were still fighting or had been injured or died in Vietnam, at a time when the draft had not yet ended, these potential future conscripts and their parents and friends saw little to fear from merely reading about war.[24]

In initially finding for the school district in 1974, Judge Krupansky determined that the banning action was taken lawfully, “in good faith…not [being] arbitrary and capricious”.[25] It is noteworthy that Krupansky also painted the picture in his written judgment that the school’s committee and Board deliberations in 1972 were “open and calm in nature” and the decision to ban the books “fair”.[26] This, it turns out, was not an entirely accurate representation of events. In the 1976 appeal of the case, it came out in evidence that when the school’s Citizens Committee reviewed the various novels recommended by teachers in 1972, committee members used terms such “completely sick” and wrote “GARBAGE” (capitalised in the original) in their notes when reviewing the novel God Bless You Mr. Rosewater, which was banned by the board at the same time as Catch-22.27 This evidence was noted in the Appeal Court judgement, and whilst not commented on in any further detail by the three judges, it must surely have had some significance for them for it to be noted: presumably the judges did not take well to the intemperance of the comments. Whilst this additional evidence does not reveal the precise views of any of the parties involved in the banning of Heller’s novel, it does at least indicate that the supposedly quiet, scholarly consideration of that year’s recommended novels by school and citizen committees in 1972, as presented in the first court case, was anything but.

Who was really threatened by Catch-22?

Unfortunately, if board or committee documents from 1972’s consideration of Catch-22 do still exist, they are not publicly available. One might then be left forever pondering what so threatened those who had the novel banned from the curriculum and removed from the library in the first place, potentially forever locked away were it not for Appeal Court Judge Edwards’ 1976 judgement overturning the banning of the novel and ordering its immediate return to the school library.[28] In his judgement, Edwards noted: “Once having created such a privilege [a library] for the benefit of its students…neither body [the State of Ohio nor the Strongsville School Board] could place conditions on the use of the library which were related solely to the social or political tastes of school board members”.[29] Presumably, evidence was heard during the appeal that led him to make this observation. It would be fair to conclude then, to borrow the judge’s phrase, that Catch-22 was not to some Board members’ social or political tastes. This at last casts a light on the issue of who or what felt threatened by the text at the point it was banned. If one reverse engineers the judge’s comment, it is reasonable to conclude that whilst the Board members who objected to Catch-22 did so voicing some perceived threat to the students who might read and study the novel, no such threat ever really existed. In talking only of a banning decision based solely (his word) on the social or political tastes of Board members, Judge Edwards clearly indicates that the only threat was to the board members themselves who had a personal, negative reaction to the novel, rather than there being any genuine, demonstrable, proxy concern for, or risk to the students.

Looking back half a century on, the threat that the Strongsville School Board imagined if students were allowed to read Catch-22 looks patronising, socially and contextually irrelevant, and not a little ridiculous, whereas, interestingly, on this occasion at least, history treats Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger fairly well. The threat that the president and Kissinger perceived from publication of the Pentagon Papers, not least that lives would be put at risk, looks reasonable and understandable.

Perhaps the most significant facet of all though, is that in those strange days of early 1970’s America, both attempts at suppression failed. Whilst history tends to present the United States as a deeply conservative country, not least in that period, in the end, in these two cases at least, it was liberalism that quite clearly prevailed.

This article was written by Nick Berbiers – Library and Information advisor – August 2023

Notes

[1]: Mark Lawson, “Eight Years, Two Titles and One Well-Timed War: How Catch-22 Became a Cult Classic,” The Guardian, 20 June 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/jun/20/george-clooney-joseph-heller-catch-22.

[2] Anthony Summers, The Arrogance of Power: The Secret World of Richard Nixon. (London: Phoenix Press, 2000),385.

[3] In his memoirs, Nixon seems to imply that he was immediately enraged, making no mention of his conversation with Kissinger, whereas biographer Richard Reeves is not alone in suggesting that Nixon was relatively unconcerned until the phone call with Kissinger. Richard M. Nixon, RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon. (New York: Grosset & Dunlop, 1978), 508-9; Richard Reeves, President Nixon: Alone in the White House. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001), 333.

[4] Bruce E. Altschuler, “Is the Pentagon Papers Case Relevant in the Age of WikiLeaks?” Political Science Quarterly 130, no. 3 (2015): 404. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/polq.12359.

[5] Ibid, 404.

[6] For example, Reeves, op.cit, 333.

[7] Historian and Nixon biographer Robert Dallek notes the pair’s great capacity to goad each other. Evan Thomas, “Nixon, Kissinger: A Deeply Weird Relationship,” Newsweek, 13 May 2007, https://www.newsweek.com/nixon-kissinger-deeply-weird-relationship-101575.

[8] Nixon, op.cit, 508.

[9] Ibid, 509.

[10] Ibid, 508-9.

[11] Henry Kissinger, The White House Years. (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1979). 729-30.

Read more : Why Is My Charcoal Grill Not Getting Hot Enough

[12] Kissinger (1999), op.cit, 52-3; Richard Nixon, Leaders. (London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1982), 28.

[13] William R. Glendon, “The Pentagon Papers – Victory for a Free Press Symposium – the Day the Presses Stopped: A History of the Pentagon Papers Case.” Cardozo Law Review, no. 4 (1998): 1305. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/cdozo19&div=52&id=&page=.

[14] Lev Grossman, “All-Time 100 Best Novels – Catch-22,” accessed Feb 18, 2020, https://entertainment.time.com/2005/10/16/all-time-100-novels/slide/catch-22-1961-by-joseph-heller/. [15] Anupama Pal, “Banning Joseph Heller’s Catch-22: The Case of Minarcini V. Strongsville City School District and Issues of First Amendment Rights, Intellectual Freedom, and Censorship,” Elon Law Review 8, no.41 (24 February 2016): 44. https://www.elon.edu/e/CmsFile/GetFile?FileID=449.

[16] Ibid, 43.

[17] Ibid, 43.

[18] Ibid, 44-47.

[19] President Nixon first used this term in a televised speech on November 3, 1969. Nixon (1978), op.cit, 409.

[20] “Minarcini V. Strongsville City School District, 384 F. Supp. 698 (N.D. Ohio 1974),” accessed Feb 10, 2020. https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/384/698/1370485/.

[21] Joseph Heller, Catch-22. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1961), 122.

[22] Ibid, 171.

[23] “Minarcini” (1974), op.cit.

[24] The draft ended the following year, June 30, 1973. “Vietnam Lotteries,” accessed Mar 31, 2020. https://www.sss.gov/history-and-records/vietnam-lotteries/.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Pal, op.cit, 48.

[27] “Minarcini V. Strongsville City School District 541 F.2d 577 (6th Cir, 1976),” accessed Feb 10, 2020. https://www.acluohio.org/archives/cases/minarcini-v-strongsville-city-school-district.

[28] The specific legal right of the school board to reject the book as part of the curriculum was upheld though.

[29] Minarcini (1976), op.cit.

Source: https://t-tees.com

Category: WHY